-

Tactical Tennis #12 – Fedal In Miami and Rowdy Crowds

In today’s episode we take the Miami crowds to task for acting like a bunch of yahoos. But that’s not all of folks. Of course there’s analysis of the Federer-Nadal final. Then we spend a good amount of time answering the big question: just how will Nadal respond to four straight losses to Federer?

/RSS Feed

/RSS Feed -

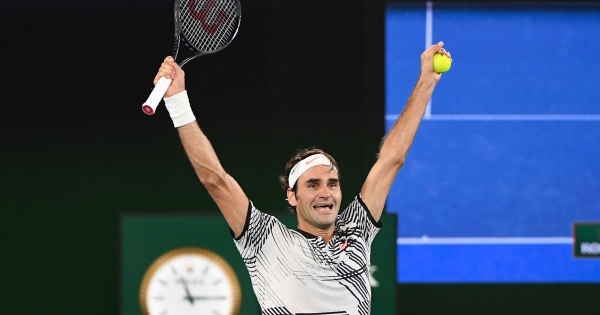

Tactical Tennis #5 – Federer Wins #18

In Episode #5 of the Tactical Tennis Podcast, Glen and Jacob discuss the men’s open final from the 2017 Australian Open.

/RSS Feed

/RSS Feed -

18

In 2006, David Foster Wallace wrote a beautiful piece for the New York Times aptly titled “Roger Federer as a Religious Experience.” It is considered by many to be one of the best pieces of sports writing ever done. In 2006, it simply rang true. Federer was in full flight, at the height of his considerable powers. Watching him play tennis during that time was almost surreal. In every single match he would provide a highlight reel that, years before, would have done for an entire tournament. There seemed to be simply nothing he could not do with a tennis racquet as he blithely hit impossible winners with a flick of his wrist. Those were the early years, the easy years.

Now we know better. It began with Nadal, of course. At first, it was easy to dismiss the inevitable yearly defeat at Roland Garros. Nadal was a clay-court specialist after all, and the kid was pretty good on the dirt. But as Nadal’s game developed, we saw a side of Roger Federer that had seemingly disappeared with the beginning of 2004. Doubt, hesitation, and eventually even a hint of fear. Against Nadal, gone were the broad sweeping groundstrokes and confident finishes. Not entirely, of course. Federer still played with power and grace, but against Nadal he almost always seemed off-balance, unsure of his footing. There were inevitably some marque performances, particularly indoors and on the grass. But as the hard courts slowed, and the grass slowed, we watched Nadal chip away at Federer’s legacy with one buggy-whip forehand to Federer’s backhand after another.

When Nadal took Federer’s Wimbledon crown in 2008, it seemed almost an affront. But as Federer broke down crying on the podium after yet another Grand Slam defeat to Nadal at the Australian Open in 2009, there was almost a sense of inevitability to it. Watching Roger Federer play was no longer a religious experience. It was entirely a human experience.

Federer broke down during the Australian Open trophy presentation in 2009

There was a pattern to their Grand Slam meetings best summarized by their 2006 French Open Final. Federer came out serving sharply, and hitting his sublime forehand with authority. He took the backhand early, and drove it effectively both cross-court and down the line. His timing was impeccable, his instincts moving forward flawless. After a comfortable and commanding first set, the second set opened well enough. Then came the game. Serving at 0-1, Federer opened up a 40-0 lead on his own serve with an easy forehand winner into the open court. He looked set for a routine hold. Federer hit a strong serve up the T, and Nadal chipped a floating backhand return that the linesman called out. In a gesture of sportsmanship, Federer requested the umpire check the mark as he felt it was good (which it was) and the point was replayed. The second time around, Federer netted an easy inside-in forehand for 40-15. Federer pulled Nadal wide with his serve and came into the net for an easy forehand volley into the open court. He missed it. At 40-30, Nadal scrambled and somehow won a cagey point that had both players at the net. Federer netted another routine forehand to hand Nadal a break point, and then saved it with a sharp serve and volley point. A netted easy backhand from Federer, and then Nadal pulled a beautiful backhand passing shot to seal the break on what should have been a routine hold.

Despite being the picture of poise and surety against everyone else, there has always been a sense of fragility when Federer plays Nadal. People usually watched Federer play for the spectacle of it – the result was a foregone conclusion. But against Nadal one couldn’t help but feel nervous, anxious even. Even when he was playing well, one couldn’t shake the feeling that disaster was lurking just around the corner for the Swiss. It wasn’t, ironically the infamous Nadal “heavy topspin ball to the backhand” that was typically Federer’s undoing – that came on Nadal’s service games. Rather it was Federer virtually breaking himself with sloppy forehands and missed easy volleys. Once the lapse happened, the rest of the set/match was spent with Federer bringing inspiring offense again and again, only to be held off by Nadal’s brilliant defense. Break points would come, and come, and go, and go. Nadal would scramble, extend rallies beyond belief and somehow find the amazing pass at the crucial moment until, finally spent, Federer’s chances would fade away into nothing.

The familiar sight of Nadal with the champion’s trophy next to Federer holding the runner-up plate

As 2016 wound down, it seemed the storied history between these two greats had wound down with it. Nadal had missed much of the year with the wrist injury that had forced him to retire from the French Open. Federer took a full 6 months off after Wimbledon, not willing to risk further damage to the knee he had injured in January. Djokovic had hiccuped at the end of the year, but still seemed dominant despite Murray taking Wimbledon, the World Tour Finals, and the World #1 ranking. The next generation of young-guns were finally showing their mettle. Dimitrov came into the Australian Open on a win streak having taken the title in Brisbane (a tournament Nadal played and failed to win). Zverev had climbed to #20 in the world and showed little signs of slowing down. And of course Raonic finished 2016 ranked #3, fighting off a surging Kei Nishikori who came in at #4. It was time to pass the torch, for the next generation to come through.

Nadal and Federer had other ideas. Entering the tournament seeded 9th and 17th respectively, both players moved through the draw with determination. Nadal showed a willingness to adapt, playing more aggressive tennis than we had seen from him since the 2010 US Open. Rafa was standing closer to the baseline, taking the ball earlier and played with a clear intent to move forward and finish points. Meanwhile, Federer displayed a mettle that had previously been missing. In his entire career he’d never before won multiple 5-set matches in a slam and taken the title. After coming through against Nishikori in five, Federer easily dismissed Mischa Zverev before again going five with Wawrinka. As seed after seed dropped before them, Nadal and Federer’s meeting in the final had a sense of destiny about it.

In the end, it came down to courage. Not Nadal’s courage – there has never been any doubt of that. Never in all their Grand Slam meetings has Nadal failed to do his part to create a great match. It is Federer who has so often fallen short. Federer who has wilted, caved, shrunk from the moment. One chipped backhand return after another, we have spent a decade watching Federer fade before his great rival. Not this time.

Federer came out from the beginning playing the style he had used the entire tournament – hitting aggressively off the ground, standing high up in the court and coming forward. Certainly it had its effect on Nadal, who was forced back in the court and put on his heels. Federer wrapped the first set up in tidy fashion, dominating on his own serve and taking his one break opportunity on Nadal’s.

Given the drama that was to come, it is surprising that perhaps the most important game came in the second set – a set that Federer lost. Having gone down a break, and failing to break immediately back, Federer then dropped a second break. The Federer Express seemed headed for a classic derailment. This was the moment – if Federer was to abandon his strategy it was to be now. In the face of a blowout set, Federer kept to the plan. He stayed up on the baseline, hit over his returns and found three forehand winners to break back for 1-4. It wasn’t enough to save the set, but it was enough to keep the faith.

As Federer began to fade in the fourth, one couldn’t help but feel that growing sense of the inevitable. When the fifth set opened, it seemed it was only a matter of time. Nadal broke Federer immediately for 1-0. Federer pushed back, earning two break points in the next game. It was classic Federer-Nadal. Every time Federer got a chance, Nadal came up with some brilliant piece of play and erased it. Nadal 2-0. Federer held at love, and then earned another break chance. Another winner from Nadal. Try as he might Federer just couldn’t break through. Federer held easily again for 2-3, and Nadal stepped up to serve.

On the first point, Federer for once came out ahead after a long rally. He stepped into a high backhand and casually swiped a cross-court winner that Nadal didn’t even run for. At deuce, another cross-court backhand winner. Nadal did run for this one, but to no avail. Courage. When Nadal missed an inside-out forehand wide, the match was level. Federer’s second serve ace at 40-0 saw him back in the lead for the first time in almost an hour.

It has never been Nadal’s way to give his opponent anything – what you get from Nadal you take. The Spaniard found himself down 0-40 in his next service game. With Federer having not lost a point on serve in some 20 minutes, it seemed as though Federer had three virtual match points on his racquet. Nadal saved one break point, then another and another. Federer pushed ahead again with a perfectly hit forehand winner after an incredibly long rally, only for Nadal to level the game yet again. It seemed as though Rafa could keep the match level on will alone. Another long rally, but again Federer got the better of it with a forehand approach that Nadal forced wide.

With Rafael Nadal serving a break point down, at 3-4 in the fifth set of the Australian Open Final, Roger Federer hit the most important backhand return of his life. Nadal spun the ball high and wide, the same serve we’ve seen him hit to Federer a hundred times before. Federer did not slice the backhand. He stepped forward, caught the ball on the doubles sideline and drove it cross-court in a sharp angle. Rafa ran as he always runs, and standing almost a body length outside the court hooked a viciously curving forehand straight into the tape. Break.

As Nadal’s optimistic challenge on match point failed, the expression on Federer’s face was a complicated one. It was not pure joy, but rather a blend of emotions. Joy of course, but also relief, disbelief, and perhaps, vindication. Maybe it is fitting that the final shot hit in this match was a Federer forehand winner. It is, after all, the shot upon which his career has been built. However it is Federer’s backhand that is a microcosm of his entire rivalry with Nadal. The shot that has been both revered and scorned in turns. The shot that most experts said would inevitably break down. There was never anything technically wrong with the shot, of course. Backhands over the shoulder with 4000 rpms are hard for anyone, whether you hit a one hander or not. It was always about mentality, and belief. In the fifth set, the time when in the past Federer had always been at his weakest against Nadal his backhand was at its best. Of the 14 backhand winners Federer hit on the match, eight of them came in that final set. On this stage, at this moment, Federer stepped into the court and took his shot.

It was never about the stroke. It was always about the courage.

-

Tactical Tennis #4 – Aussie Open Men’s Semis Review, Federer-Nadal Preview

In Episode #4 of the Tactical Tennis Podcast we review both men’s semi-finals from this year’s 2017 Australian Open. Each of the matches is broken down in terms of what the stats tell us, as well as some of the patterns, tactics and larger picture strategies employed by each of the players. Dimitrov’s prospects moving forward are discussed at length, as well as a healthy argument about how many more years Nadal could have at the top of the game. Then talk turns to the men’s final – the dream match of Federer and Nadal that nobody dared to imagine when the tournament began.

/RSS Feed

/RSS Feed -

Two Swiss, One Spaniard – Why Wawrinka Succeeded Where Federer Failed

When Wawrinka held aloft the Australian Open trophy it was the culmination of years of sitting on the cusp of a breakthrough. There were hints of course – the two epic five set matches against Novak Djokovic at the Australian and US Opens in 2013 for one. Long possessed of one of (if not the) finest one hand backhands in the game, Stanislas Wawrinka finally stepped out of Roger Federer’s shadow, doing so with an exclamation point by beating Nadal in the final a mere two days after Federer fell to the Spaniard himself. While some Nadal fans point to his injury as being the deciding factor in the final, Wawrinka was clearly outplaying Nadal right up until the moment the Spaniard took his medical timeout. So why was Wawrinka able to be so effective where Federer failed? Given their grand-slam tallies sit at 17 and 1 respectively, even a weakened Federer is still at a similar ability level to Wawrinka on the court. This was a victory of ideas, not merely of playing quality. Where Federer took the court looking largely directionless Wawrinka was a man with purpose. So let’s take a look at the matches, and highlight the key differences between the two Swiss men in their tactics.

Looking For Patterns

I’ve often drawn the analogy that high level tennis is played like chess. Genuinely unforced errors become a relative rarity – instead the players are competing for position. Underlying all of this is the importance of patterns. Patterns are everywhere in every sport, and all top athletes employ them. In American Football, they have set plays, with names. In what the rest of the world calls “Football” (and Australians and Americans call “Soccer”) even in the seeming madness there are techniques, combinations and patterns that the teammates have done together countless times. The defenders move (hopefully) with a level of coordination that isn’t always obvious to the casual observer. These patterns exist because, as humans, we get tend to get better and better at things the more that we do them. In the realm of sport, familiarity doesn’t breed contempt: it breeds competence and confidence. We tend to do what we know, and what we know well we do well.

When there are marked contrasts in styles, these patterns become more important than ever as the two players compete not just for points, but to impose their own style of play upon their opponent. An obvious example is Rafter-Agassi, a riveting matchup that produced some amazing matches. Agassi couldn’t hope to volley like Rafter, and Rafter couldn’t hope to outhit Agassi from the ground over the course of three or five sets. So, they each struggled to impose their game. Rafter serve and volleyed, forcing Agassi to attempt the pass. Then on his own games, Agassi would keep the ball deep, and try to prevent Rafter from coming into the net. In these two matchups things are somewhat different. All of these players like to finish points with their forehands (yes, even Stan “The Backhand” Wawrinka!) and given Nadal’s left-handedness it becomes a battle to see who can create more positive forehand opportunities for themselves.

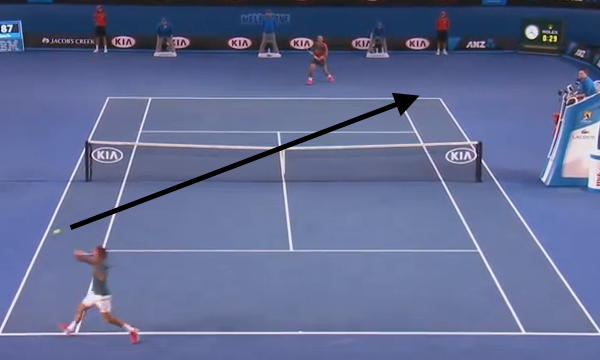

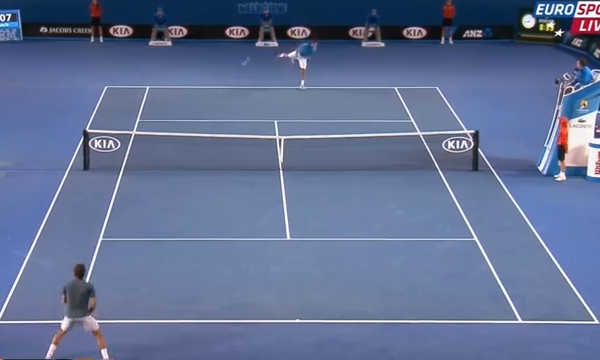

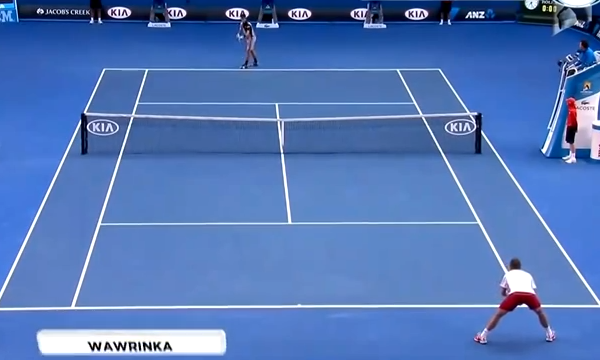

Federer Problem #1: Federer Let Nadal Dictate With His Forehand

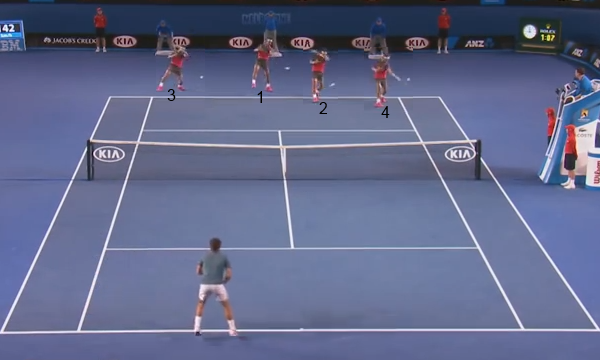

The above image shows the forehands of Nadal in a single point beginning from Federer’s return of serve. Nadal gets to hit the first two from near the center of the court and as a result immediately has Federer on the defense. Indeed Federer was stuck hitting slice backhands for the entire rally after the return, which ended with Nadal hitting a backhand dropshot winner off shot #5. Unfortunately for Federer this is a pattern of play that is all too familiar on Nadal’s serve. Nadal slices a serve into Federer’s backhand, and then proceeds to take Federer’s fairly central, low-pace return and pound him into submission. It’s a pattern that Federer has struggled to break against Nadal, and typically once he has hit a couple of defensive slice backhands he is in serious trouble.

Wawrinka Solution #1: Turn The Tables

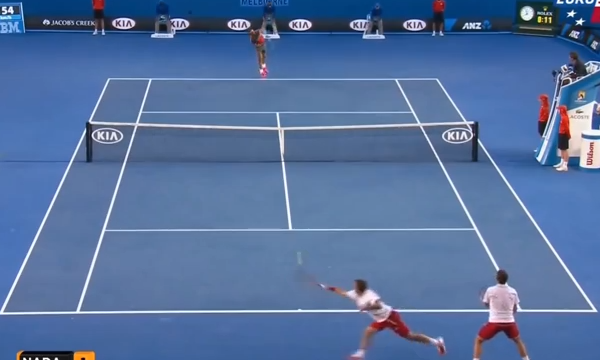

One thing Federer has always struggled to do against Nadal is take an appropriate “grinder” mentality. His game can be so mercurial, yet Nadal brings him down to earth with a brutal single-mindedness. Wawrinka has no such compunction. The beauty of his backhand aside, authors have written little about the poetry or grace of Wawrinka’s game. He is a power player and Nadal causes him no identity crisis, as we see below:

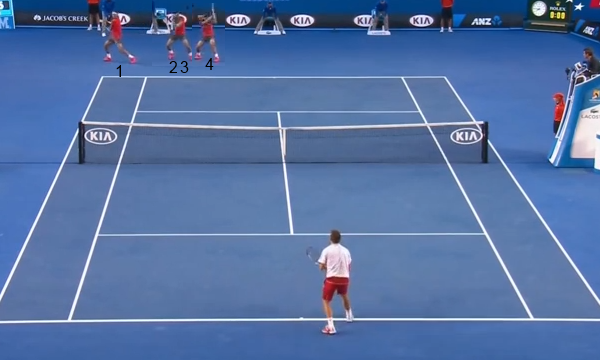

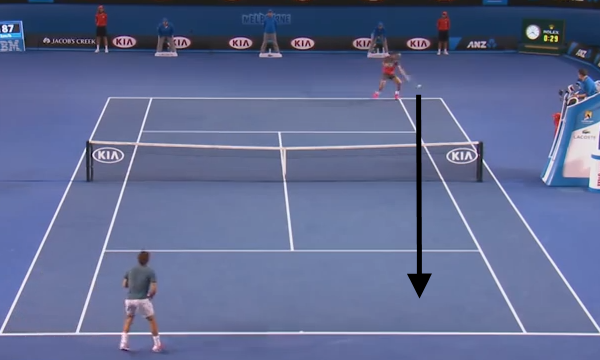

Here we see Wawrinka turning the tables. This sequence of four shots begins with Nadal’s return of serve off a Wawrinka second serve. Ironically I had to use the same Nadal image for shots #2 and #3 in this rally because they were quite literally on top of each other. Desperate to break out of this corner, Nadal takes backhand #4 down the line:

And now Nadal will finally get to hit a forehand. However he isn’t hitting it on his terms, he is hitting it on Wawrinka’s terms. Wawrinka will drive this ball with pace into Nadal’s forehand corner, and Nadal is forced to hit a skidding, defensive ball that he cannot quite get back to Wawrinka’s backhand. The result is that Stan hits another aggressive ball into Rafael’s backhand, then earns this forehand off which Nadal makes an error.

This was a pattern throughout the match: Wawrinka being willing to hit three, four or more forehands in a row into the Nadal backhand. More often than not he waited for Nadal to be the one to change direction, and then he would punish balls into Nadal’s forehand corner. It isn’t that Federer isn’t able to construct this type of point – he did so a few times during the match and won the point almost every time. But rather it didn’t seem a high priority to him – it was not a pattern that he came on court determined to execute. Instead…

Federer Problem #2: Rushing Into The Net

One of the highlights of Federer’s play throughout the tournament leading into this match was his net play. There was a crispness to his movement going forward that showed a marked improvement in this area. Indeed if one can be forgiven the obvious reference, there were shades of Edberg in his prime showing in the way that Federer closed ground to the net to finish points off. However one key element in this has been the timing with which Federer has done so. There has been a patience to the whole process – a sense of waiting for the precise moment. Often times Federer has simply hit an aggressive ground stroke, then only started moving forward when his opponent was clearly off-balance or committed to a defensive shot. Against Murray, who possesses one of the better passing games in tennis, Federer went 49 of 66 (74%) in his net approaches. Against Tsonga he was 34 of 41 (83%) at net.

In his match against Nadal that poise was gone. Rather than wait for the right moment, Federer seemed determined to push forward. Rather than wait until Nadal was genuinely unable to play an aggressive pass, Federer often came in behind forehands hit on or around the baseline. Against lesser athletes this would be a more feasible play given the quality of Federer’s forehand. However Nadal is not just fast, he is strong and explosive. Even in compromised positions, Nadal is able to find stability and attack the ball with spin and power.

Wawrinka Solution #2: Patience is a Virtue

While Wawrinka doesn’t quite have Federer’s net proficiency he’s no slouch there either – after all, he does have an Olympic gold medal in doubles on his tennis resume. However he seems to have a better understanding of when to take the net against Nadal. On the same ball/court positioning that Federer was hitting approach shots, Wawrinka was far more content to pound another ball into Nadal’s backhand and play for court position. Where Federer came forward 42 times against Nadal, Wawrinka came to net just 12. Where Federer won only 23 of those 42 net points (a 55% success rate), Wawrinka won 11 of his 12 (a 92% success rate).

A lot of this comes back to patterns. Wawrinka had a clear plan for success against Nadal, and coming to the net frequently was not a part of that plan. When Wawrinka got ahead in the point, he knew exactly what he wanted to do. Federer was searching for answers – in his near 10 year rivalry against Nadal he still has not truly found a path to victory that doesn’t just involve playing really, really well.

Federer Problem #3: Backhands Up the Middle

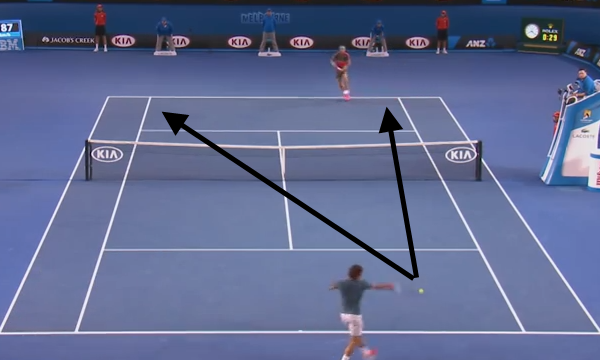

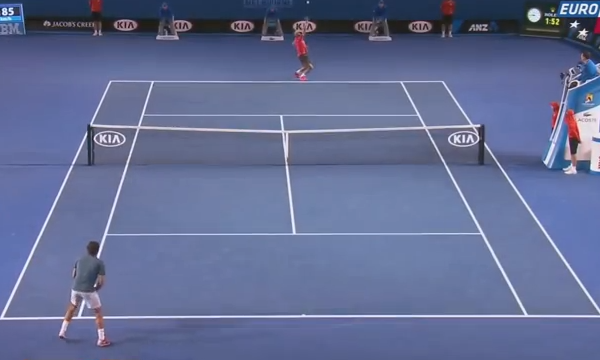

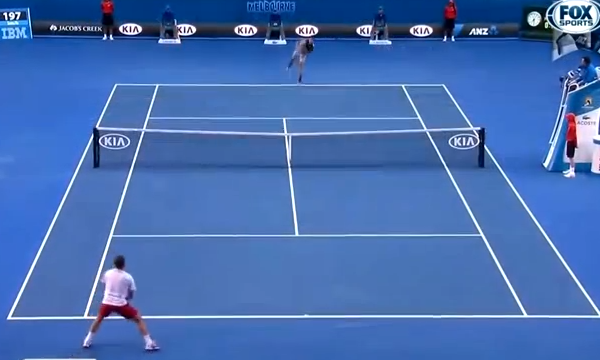

Against some opponents this is actually a good play – by hitting the backhand up the center of the court, you take away the angle making it easier to run around a backhand to hit a forehand. Against Nadal this doesn’t work because Nadal can take his forehand inside out from the center of the court far better than most right handers can do the same with their two-handed backhand. Additionally Nadal generates so much topspin on his forehand that even from the center of the court he can still open up the angle to Federer’s backhand. However rather than show you more pictures of Federer doing the wrong thing, I’m going to touch back to a comment made prior to the match about Federer needing to use his slice to good effect. Here is one example of how he can do so:

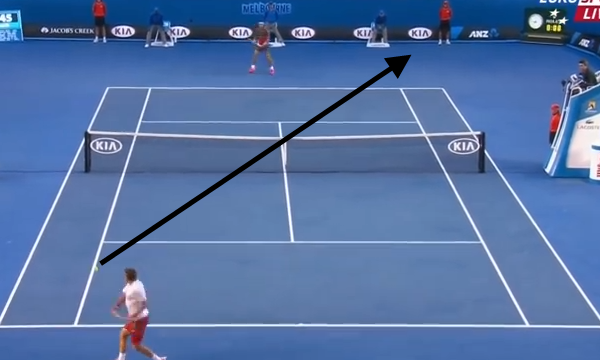

In the first image we see Federer hitting his slice backhand. As you can see the ball is above his shoulders, the point at which Federer generally struggles to be as effective with his topspin backhand due to to primary pulling muscle of the deltoid simply not being as strong in the higher plane. However when we hit a slice above the shoulder, the larger latissimus dorsi gets to help out since we are also pulling downwards making us a lot stronger. So, Federer is able to hit this shot with reasonable pace and penetration and create some angle:

Here you can see the ball is in the doubles alley at contact, and down at knee height for Nadal – a less than optimal striking point for Nadal’s forehand stroke. Even more importantly he is having to hit this ball on the run. Meanwhile we can see here Federer is bisecting the probably angles of return already, which means when Nadal is striking the ball, Federer is balanced and ready to react in either direction. Due to his position, his having to hit on the run and the lower contact point Nadal’s forehand is pulled more central than he would like, which leads to…

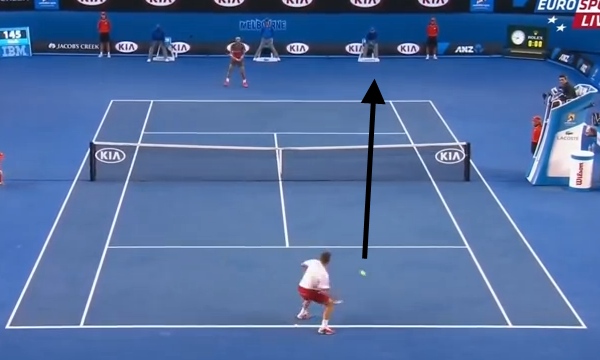

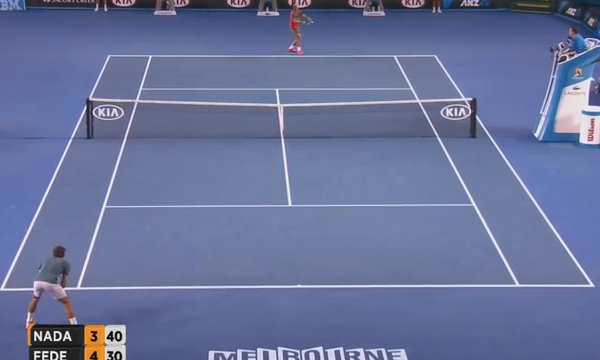

Federer gets a forehand below shoulder height, standing near the center of the court. He has two good attacking options – to hook the ball cross-court with some angle or to play it back down the line. Nadal is scrambling to reach the point of bisection, and at contact here you can see that he is a good 15 or so feet from being in position. As such his weight is traveling from his left to right in an effort to best be able to cover both of Federer’s options. Note the contrast with the previous frame where Nadal was hitting his forehand. There Federer was balanced and weighted neutrally.

And the finish. Federer goes back down the line, and Nadal is left too off-balance to be able to react. The Federer forehand goes down the line for a winner. This was all made possible because Federer opened the court up to the Nadal forehand in a way that prevented Nadal from being able to attack him. It isn’t that Federer needs to do this with a slice backhand specifically – Wawrinka did through most of his match with Nadal using his topspin backhand. However when you watch this match Federer had plenty of opportunities to drive balls wide to Nadal’s forehand and he failed to do so. Whether that’s a question of intent, or an inability to do so only Federer can say.

Federer Problem #4: Returning the Nadal Serve

When you’re only winning 27% of return points against your opponent’s first serve things aren’t going well. When you’re only winning 27% against their second serve, well… things are going horribly wrong. That’s exactly what happened to Federer against Nadal in a continuation of his long-standing inability to do anything with the Spaniard’s delivery. Nadal won 73% on his first serves, and 73% on his second serves. Allow that to sink in a moment. It didn’t matter whether Nadal made his first serve or not – he was just as likely to win the point hitting a second serve. In comparison, against Wawrinka Nadal won only 60% of his first serve points and a mere 42% of his second serve points. Why is that?

Nadal’s serve has a lot of movement on it. In fact, some rough measurements showed me that from the bounce to hitting the back wall it’s got some 4-5 feet of sideways movement. That’s a lot. The end result of this is that Nadal can slide the ball into Federer’s backhand in such a way that makes it incredibly difficult to run around it. So, he’s practically guaranteed that Federer is stuck hitting a backhand return. Add to this the fact that Nadal is good at making Federer stretch in order to hit said backhand return and you’ve got a setup that’s difficult for Federer. We’ve seen Federer flick some amazing passing shots over the years off his one-handed backhand while stretched and on the run. However the return is different. For one he’s not on the run so he has less momentum behind him. Secondly getting the ball past someone at the net doesn’t require pace as much as it does placement. Stretched off the return Federer struggles to generate pace. As a result his returns frequently fall short, and Nadal is immediately in control of the point.

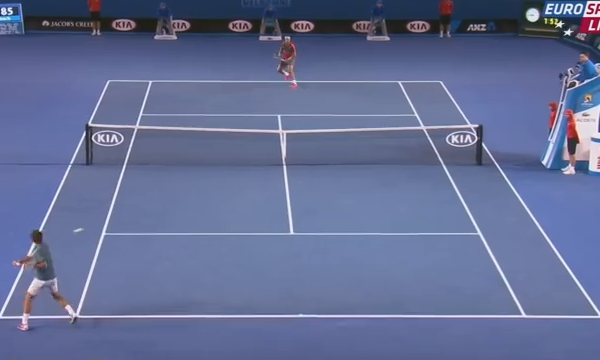

It is in this regard, more than any other, we have ample evidence of Federer’s absurd unwillingness to change even a losing strategy when playing Nadal. Adjusting where you are standing in order to adapt to your opponent’s serve may not be Tennis 101, but it certainly should be standard fare for one of the greatest players in history. Doing so when your opponent’s service location is utterly predictable is just common sense. To put it in perspective, on the deuce court Nadal hit 3 first serves at the body, and 25 down the T to Federer’s backhand. Number of serves out wide to Federer’s forehand? 0. Zilch. None. Nada. So let’s take a look at where Federer normally stands to return serve on the deuce court:

First we have Federer returning against Murray.

Then we have Federer returning Tsonga’s serve on the deuce court.

Now Murray split his deuce court serves between wide and T 50-50. Tsonga served 9 wide serves and 12 T serves during the match. Now it isn’t as though Federer has never played Nadal before. Prior to this match they had faced off 32 times. Surely, given the huge preponderance of serves going to the backhand Federer would make some adjustments from the beginning of the match…

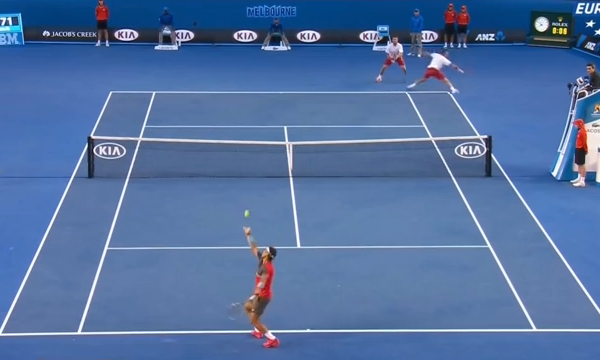

Or perhaps not. As we can see, we’re a little over halfway through the first set. Nadal has yet to hit a single serve to Federer’s forehand on the deuce court and Federer is standing perhaps 2-3 inches to the left from his normal receiving position. What about on the ad court? First we have Federer waiting to return on the ad court against Murray.

And then there is Tsonga…

And finally against Nadal.

And once again we see a relocation measured in inches rather than feet. Certainly Federer takes a small hop to his left once Nadal tosses the ball, but he does nothing to actually deter Nadal from pursuing his chosen course. Now I wish I could say that we see Federer adapt over the course of the match – not an unreasonable hope for such a talented player. And yet, Federer has failed to make a real adjustment to Nadal’s serve across his entire career, let alone the course of a single match. We do see Federer try a couple of different things. Early in the first set, he actually runs around a Nadal serve on the ad court and hits a clean winner with his forehand. I can’t recall if he actually attempts a second time during the entire match, but one would think this would surely be a play worth trying a lot if it met with some success.

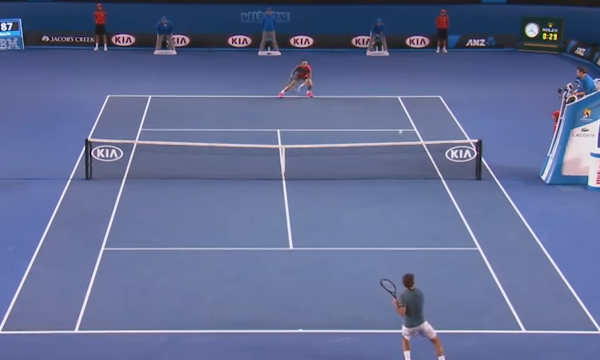

Federer also tries standing further back, a rather thoughtless play against someone who is serving at relatively low place and focusing on the angles. In fact this is exactly the opposite advice a good coach gives to a player who has an opponent serving the way Nadal does during this match. Why? Let’s take a look…

Here we see Federer has backed up, and moved slightly wider. This is an appropriate adjustment to make against an opponent who is serving with great pace but without a lot of angle on their serve. Unfortunately for Federer, Nadal is doing the opposite and as a result, this is where Federer ends up standing when he makes contact with the return on this serve:

Yes, that is Federer standing with both feet outside the doubles side line attempting a backhand return. It may come as no surprise that Federer failed to win this point. So what should Federer do instead? Oddly enough, Federer did the right thing a handful of times, and to good effect. He stood up closer to the court, stepped in and cut off the angle before he was pulled too wide. Below is an example of Federer’s position on contact when he did so:

It’s quick to see that his court positioning is significantly better here than in the previous image. Hitting from higher in the court means Nadal has less time to recover from his serve, and Federer has a much shorter distance to travel to be in good position for the next ball. However he did this a scant few times as a whole, and generally stayed with the same, weakly bunted backhand return for most of the match.

Wawrinka Solution #4?: A Mixture

It’s a little disingenuous to refer to this one as a “Wawrinka Solution” for a few reasons, but we’ll get into those briefly. First, let’s take a look at where Wawrinka stands to return Nadal’s serve at the start of the match and compare it to his normal return positions. We’ll start with Wawrinka’s return position against Djokovic on the deuce court:

So where does he stand to start the match against Nadal on the same side?

We can see that Wawrinka has shifted somewhat to his left, and is also standing a little deeper than he does against Djokovic. Similar to what we saw with Federer, this puts Stan on the stretch as the ball has more time to move and cut away from him due to his deeper position.

So how about on the ad court? Let’s see where Wawrinka stands to return against Djokovic on that side:

Fairly standard fare. So where does he stand to return Nadal’s serve on the ad court?

Wait a second. We see here that Wawrinka’s taken up much the same position as he did against Djokovic, and is getting stretched out in the same manner that Federer was. So what gives? Why is Wawrinka’s positioning getting him breaks where Federer failed to? For starters, Nadal serves completely differently against Wawrinka than he does against Federer. Remember how Federer didn’t get a single serve to the forehand on the deuce court? Nadal served 11 – eleven – out to Wawrinka’s forehand on that side. And the ad court? Sit down, because whereas only 14% of Nadal’s ad-court serves were down the T against Federer, 37% of Nadal’s serves went there against Wawrinka (with 37% going wide and the rest at the body).

Given these serving patterns, Wawrinka was right to hold something very close to his normal lateral position against Nadal. So how did he get the break? The first break, at 2-1 in the first set was entirely Nadal’s doing. The opening point of his second service game, Nadal stretched Wawrinka down the T (it’s actually the deuce court return image above), got a short, weak reply and hit a poor drop-shot off it that Wawrinka then passed him on. Then at 15-30, Nadal served wide into the ad court, got another weak reply and after coming into the net hit a poorly played backhand drop volley instead of punching it into the open court for a winner. Wawrinka again ran the ball down and drove a passing shot that Nadal couldn’t return. Then finally on break point Wawrinka ran around a body serve to hit a solid top-spin forehand return. However it was solid, not spectacular. Wawrinka started the point neutral, not ahead, and it was only through superior pattern play (namely breaking down Nadal’s backhand) that he clinched the break.

As the match progressed, Wawrinka showed a willingness to move aggressively to his left after Nadal’s ball toss, particularly on second serves. However on the ad side this availed him little as he was still stuck far outside the sidelines making his return. He had much better success when he stepped forward to cut off the angle and sliced a deep return. This put him in an improved court position. The truly key element here though is Wawrinka’s ability to win neutral points with Nadal, be it on his own serve or when returning.

Federer Must Find New Patterns Against Nadal

In truth Federer’s quality of return wasn’t noticeably better or worse than Wawrinka’s as a whole. The issue for Federer is that with the current patterns he employs against Nadal he has no way to win an appropriate number of neutral points to win the match. This is why his return positioning becomes a big deal – he needs to be on offense against Nadal to stand a reasonable chance. Against virtually all other opponents, Federer can start the return points neutral, or even slightly behind, and then use his patterns of play to progress to a position where he has a good chance of winning the point. Against Nadal that transition just doesn’t happen often enough. He truly needs to come at this from two directions. The first is to adjust his positioning on the serve and be willing to take more risks. The second is he needs to fundamentally change his goals when he takes the court against Nadal.

How? He must be willing to grind forehands into the Nadal backhand – a pattern that gives him good success against the Spaniard. He needs to open up the court to Nadal’s forehand, either flattening his topspin backhand out a bit or using a more aggressive slice to do so. And finally he needs to stop pressing his way into the net. Against Nadal he must only come forward when he’s got a truly short ball, or he’s seen Nadal already commit to a defense slice. Nadal is truly one of the all-time greats. Even doing everything right you simply cannot beat him every time. However with these adjustments Federer could at least begin winning his fair share.

What’s Next For Wawrinka?

This is the breakthrough that Wawrinka fans have been waiting for. “Stan the Man” has long had the tools to be a force at or near the top of the game, but a little untidiness in his play has seen him lingering most in the 10-30 range for a while. It’s telling that he’s bounced from being a top 10 player all the way down to the high 20’s, then back again… multiple times. When he plays with confidence and makes good decisions he has the sheer firepower to bludgeon his way through to the late stages of most draws. He really needs to take a page out of Agassi’s book, understanding that he can outhit most players in cross-court rallies and so be willing to do so. If he continues to play with the same discipline and belief that he showed in Australia, he’ll continue to be true factor on the big stage. The so-called “Big Four” is cracked at the seam, and nature abhors a vacuum.

-

Five Things Federer Can Learn From Dimitrov’s Match With Nadal

At Tactical Tennis we’ve talked about the similarities between the games of Dimitrov and Federer before – Dimitrov’s slowly fading nickname of “Baby Fed” is not happenstance. As such the match between Nadal and Dimitrov has greater significance for Federer than everyone else. For him it provides an opportunity to see, in live play, someone with a remarkably similar style of game tackle the tactical challenges that Nadal has to offer. Clearly Dimitrov is doing something right – despite his relatively lowly ranking and ‘up and comer status’ he’s pushed Nadal to a third set in all three of their previous meetings at small tournaments. Then, last night, Dimitrov pushed Nadal towards the edge in coming within a handful of points from victory. So what is Dimitrov doing right against Nadal? What can Federer take away from this match and carry into his semi-final against Nadal on Friday?

Nadal’s Game Plan

To ensure we are all on the same page it is important to, at least briefly, talk about Nadal’s game plan. Nadal’s goal is relatively simple – to break down the one-handed backhand. By focusing the vast majority of his play there he can both dictate play and fatigue his opponent. It is a pattern we’ve seen play out over and over in Nadal and Federer’s long and storied history – Nadal pounding high and heavy balls into Federer’s backhand until slowly the unforced errors begin, at first with a trick and finally in a cascade that results in a Nadal victory. The reason this happens is once the contact point for the one-handed backhand moves above the shoulder, the strength of the muscles pulling the arm and racket around (primarily the rear deltoid) is noticeably lower. Since the muscle is operating closer to its limit up there, it fatigues more quickly, which encourages players to use too much of their hips to compensate, thus reducing the stability of the stroke and causing an increase in errors. Additionally the decreased strength above the shoulder means the one-handed backhand player can generate less power, meaning it is harder for them to hurt you.

This forehand into the opposing backhand is the centerpiece of Nadal’s game plan. Based off of this he can fall into a variety of familiar patterns, earning shorter forehands in mid-court which he then finishes the point with. It’s clear watching him play Dimitrov that he’s dusting off the Federer Game Plan and putting it to good use. An astonishing 84% of Nadal’s first serves on the deuce court went to Dimitrov’s backhand, and 71% to the backhand on the ad court. Meanwhile Dimitrov served less than 50% of his first serves to the Nadal backhand on the deuce court, and only 61% on the ad court. By serving to the backhand, Nadal is increasing the chances of his first ball after the serve being a forehand, which then allows him to choose the initial pattern the point will begin with.

All this is well and good, but what did Dimitrov do that allowed him to foil Nadal’s game plan to a large extent?

1) Serve For The Corners

It’s hard to over-stress the importance of stretching Nadal on the return. Nadal fights off the body serve well, but Dimitrov did a great job of making Nadal reach for returns on both wings. This earned him a large number of short, mid-court forehands which he abruptly finished the point with. Particularly effective was the wide serve on the deuce court – a serve Federer usually excels at.

2) Know When To Pull The Trigger

One thing was clear from early on – Dimitrov wasn’t afraid to have long rallies with Nadal. In recent years Federer has been too quick to try to end the point against Nadal, especially off the forehand wing. Dimitrov was quite content to use his big forehand to control rallies, hitting with heavy spin into the Nadal backhand. Then, when he got the short ball (particularly off the return) he pulled the trigger and ended points with aplomb. Federer must be willing to be patient off the forehand wing, and earn the shorter balls he can then take chances on.

3) Use The Slice To Effect

Of all the things Dimitrov did well in this match, his use of the slice was at times brilliant. A key part of Nadal’s game plan is the breaking down of the one-handed backhand. Nadal loves to use his forehand to play puppet-master, jerking his opponents around the court with heavy spin. Ironically Dimitrov frequently turned the tables on Nadal in a very subtle way. He was very happy to play a deep, slow slice back to Nadal’s forehand in that cross-court rally, then periodically throw in a shorter slice down the line into the Nadal backhand. Suddenly instead of Dimitrov running all over the court, he was standing in the backhand corner and forcing Nadal to be the one doing the hard work. The slice backhand isn’t near as fatiguing as the one-handed topspin backhand because the downwards motion of the stroke involves heavy use of the latissimus dorsi (a much larger muscle than the deltoid and thus less susceptible to fatigue). The end result of this was that Dimitrov was able to extend rallies with Nadal at a low energy cost.

4) Push-Pull

I’ve noticed several comments around the web this morning talking about how poorly Nadal played. What people fail to realize is that this is in large part due to the way Dimitrov played him. Dimitrov did an excellent job of what I call “Push-Pull” – pushing Nadal back on one shot, then pulling him forward on the next ball. The pulls were rarely short enough for Nadal to treat them as approach shots, but what this did was disrupt Nadal’s excellent lateral movement and force him into movement patterns he uses far less often. By putting Nadal in such unfamiliar court positions, especially off lower, low pace balls (see the slice comments above), Nadal struggled to deal with the ensuing changes of pace and depth. Multiple times I saw him miss routine balls midway through a rally after several changes of pace from Dimitrov. Even more interesting was how often we saw Nadal go to the slice backhand last night, which is something he doesn’t like to do often. Dimitrov clearly made Nadal uncomfortable and took him out of his normal game.

5) Believe

Dimitrov took to the court like a man with a mission. This was not a nervous performance from the Bulgarian – for the first three sets Grigor played like a man who belonged. He wilted in the fourth set, but Federer should take heart from the fact that it was only then that Nadal began to look comfortable and truly in control. The courts are faster, Federer is moving better, and he is a significantly better player than Dimitrov. He could take the court, play Dimitrov’s exact game plan and come through purely by virtue of being better at pretty much everything on a court than Dimitrov is. Dimitrov’s performance should give Federer the confidence to believe he can take the match.

Federer has done a great job of sneaking into the net to finish points throughout the tournament so far – whether this is Edberg’s influence or not is difficult to say but he’s not looked this sharp in his reading of the game in several years. Federer is also showing a level of defense we’ve not seen from him in some time. The question isn’t whether or not Federer can win the match. The question is, when Federer takes the court on Friday will he be alone, or will the ghosts of failures past follow in his wake whispering defeat in his ear? With the top half of the draw looking relatively empty now, this may well be Federer’s best chance to take #18. In the same manner that Sampras played Agassi in the 2001 US Open final, it is only fitting that Nadal should be the man standing now in Federer’s way.