-

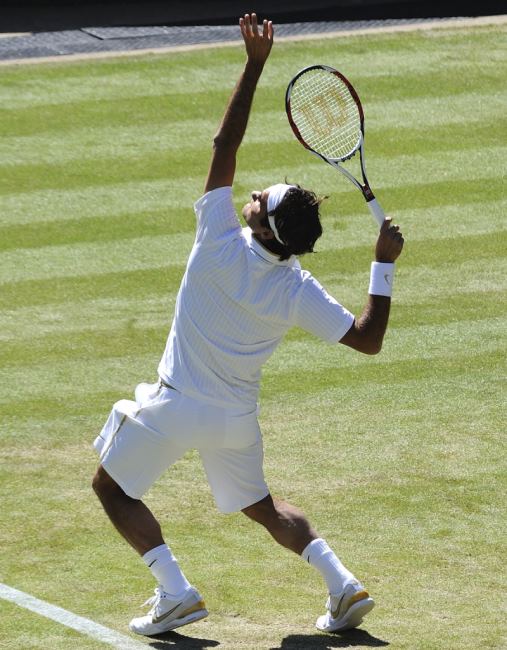

Serving Mechanics – The Jump

Introduction

4% doesn’t seem like a lot. In tennis however it can make a world of difference. 4% can be the difference between retiring a millionaire and barely making a living on the pro tour. It is the difference between being Roger Federer (54.14% of points won, 20 Grand Slams) and Andrei Pavel (50.14% of points won, 0 Slams). 4% is also the difference in Federer’s first serve % (62.1) and Stan Wawrinka’s (57.9%). Roger is 8th on the ATP’s all-time servers, while Stan sits at 61st.

Federer and Wawrinka provide an interesting contrast. They are two men who are of about the same height, who serve at virtually identical average speeds, with similar aces per match. Yet one of them is considered among the best servers of all time, while the other is not. One is a very good server, while the other is great. What is the difference?

We will use the two (and others) to contrast several aspects of the serve over the next few articles, beginning with the jump. Before we dive in further, it is highly recommended that you read the previous two serve mechanics articles on the ball toss (Part 1, and Part 2). All aspects of the serve impact each other, and understanding ball toss is a critical piece of setting yourself up for success when it comes to the mechanics of the jump in the serve.

Why We Jump

We do not jump in the serve for power (or any other stroke). This is important, because it is a fundamentally misunderstood part of biomechanics at all levels of tennis. We do not jump for power.

When we jump, we are at our maximum velocity in the instant we leave the ground. By the time we hit the ball at the peak of our jump, we are at our lowest possible velocity. Indeed, at the peak our upwards velocity is precisely zero.

The energy from the jump does not go into the ball. We exchange the kinetic energy of our jump for the potential energy of being up in the air. Once we hit the peak of our jump, gravity helps us convert that energy back into kinetic energy (by falling).

We do not jump for power, we jump for height.

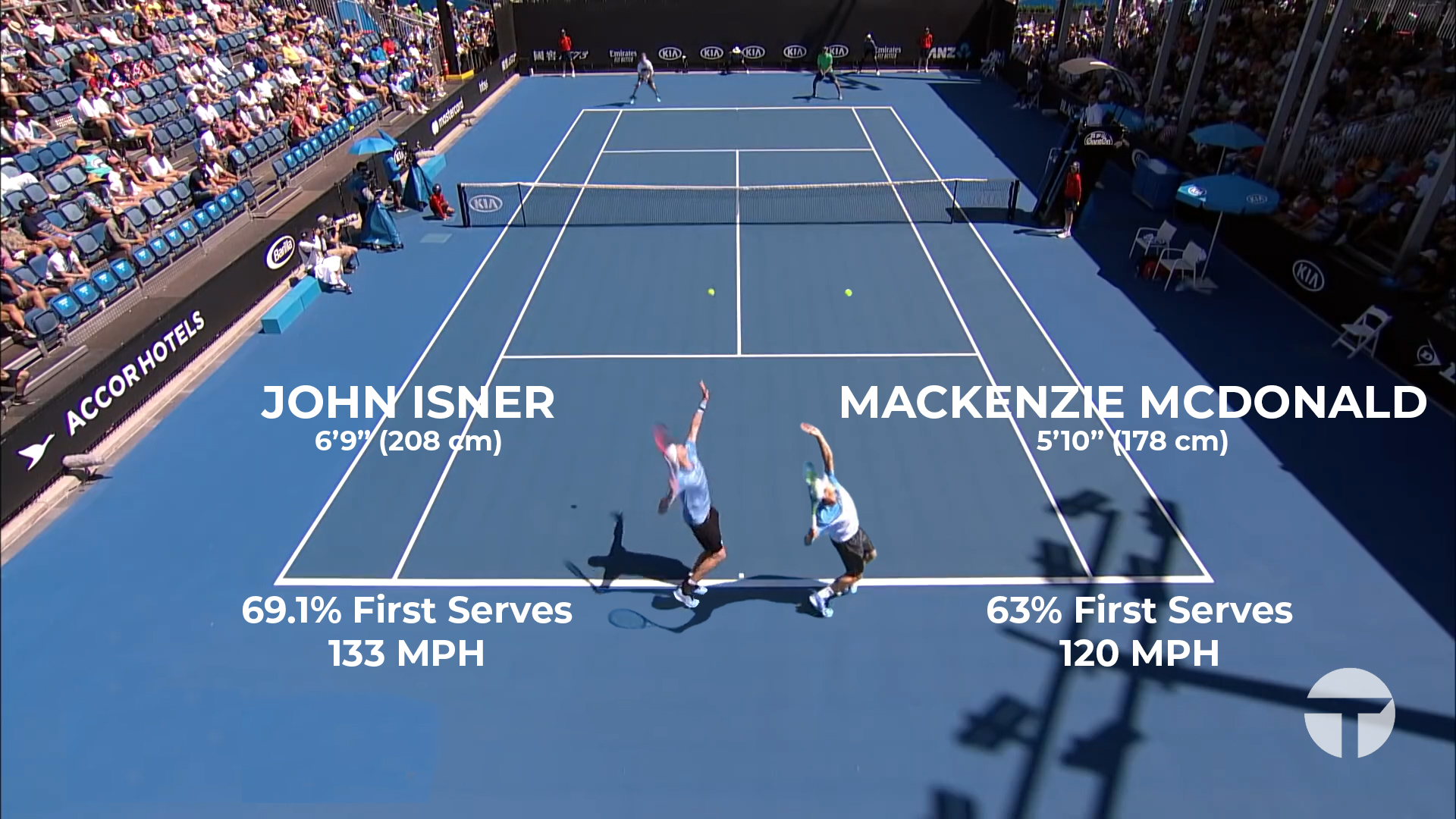

Height At Contact

The image above shows John Isner (6’9) serving at the Australian Open in 2019. To his right is Mackenzie McDonald (5’10), serving on the same court at the same tournament. We look at the size difference between the two, and intuitively understand that serving is much easier for Isner than it is for MacDonald. Isner is, to use the phrase, serving out of a tree. Relative to Isner, McDonald is serving from down in the weeds.

The interesting thing is people often don’t move past the intuitive understanding that taller is better. In truth it isn’t that taller is better. It is that making contact with the ball at the highest point possible is optimal. The higher the ball at contact, the better the serve can be.

As the contact point drops, we are forced to sacrifice velocity, consistency, or both.

A ball struck at a higher point can be hit harder, with more angle. It has a steeper trajectory into the box and bounces higher which is more challenging to return. A 5’11 player who can jump 12 inches on their serve is better off than a 6’1 player who only jumps 6 inches (all other things being equal).

Trophy Position

The trophy position is such a telling moment in a service motion. Everything up until this point has been preparation – movement to get us to this position. In its totality the trophy position is our setup for so many things – the jump, hip/shoulder rotation, arm action. Combined, these things impact control, disguise, and power. Since we are focusing on the jump in this article, we will look primarily at the trophy position as it relates to the jump.

Best Jumping Practices

Since we don’t get a running start on the serve, it might be helpful to look at how the best standing jumpers in the world do it. Many people expect professional basketball players to be the best standing jumpers, but it’s actually NFL athletes. Playing in the NFL requires more raw explosiveness. This is part of why they test jumping ability at the NFL combine every year.

So let’s take a look at Byron Jones. Jones is the greatest jumper in NFL history – his standing broad jump was over 8 feet long! But for our purposes, he also put up an astounding 44 inches (112 cm) with a vertical standing jump.

Note the starting position for his jump. Bends at the ankles, knees, and hips. Arms are swept back. Every piece of his body is poised to generate upwards momentum with maximum explosiveness. Such a starting position would be absurd for a serve. The idea is not to copy Byron Jones’ jumping position exactly, but rather to ask ourselves a question.

What elements of these jumping mechanics can we incorporate into our own trophy position without negatively impacting other elements of the service motion?

Wawrinka and Federer’s Trophy Positions

The differences between the two are fairly quickly apparent. Federer has a greater degree of flexion in his knees. His stance is a little wider, his hips and shoulders significantly more closed off to the court. For the purposes of examining the jump, the rotation matters less to us right now (although it does impact other elements of the serve).

Federer doesn’t just have a greater knee bend, though. The other important facet is flexion at the hips. We gain power from our posterior chain as it straightens – hip extension is a critical part of that process. In his trophy position, Stanislas Wawrinka has little to no flexion of the hip, which means he can get little extension (essentially only what extension he can manage past a neutral hip position).

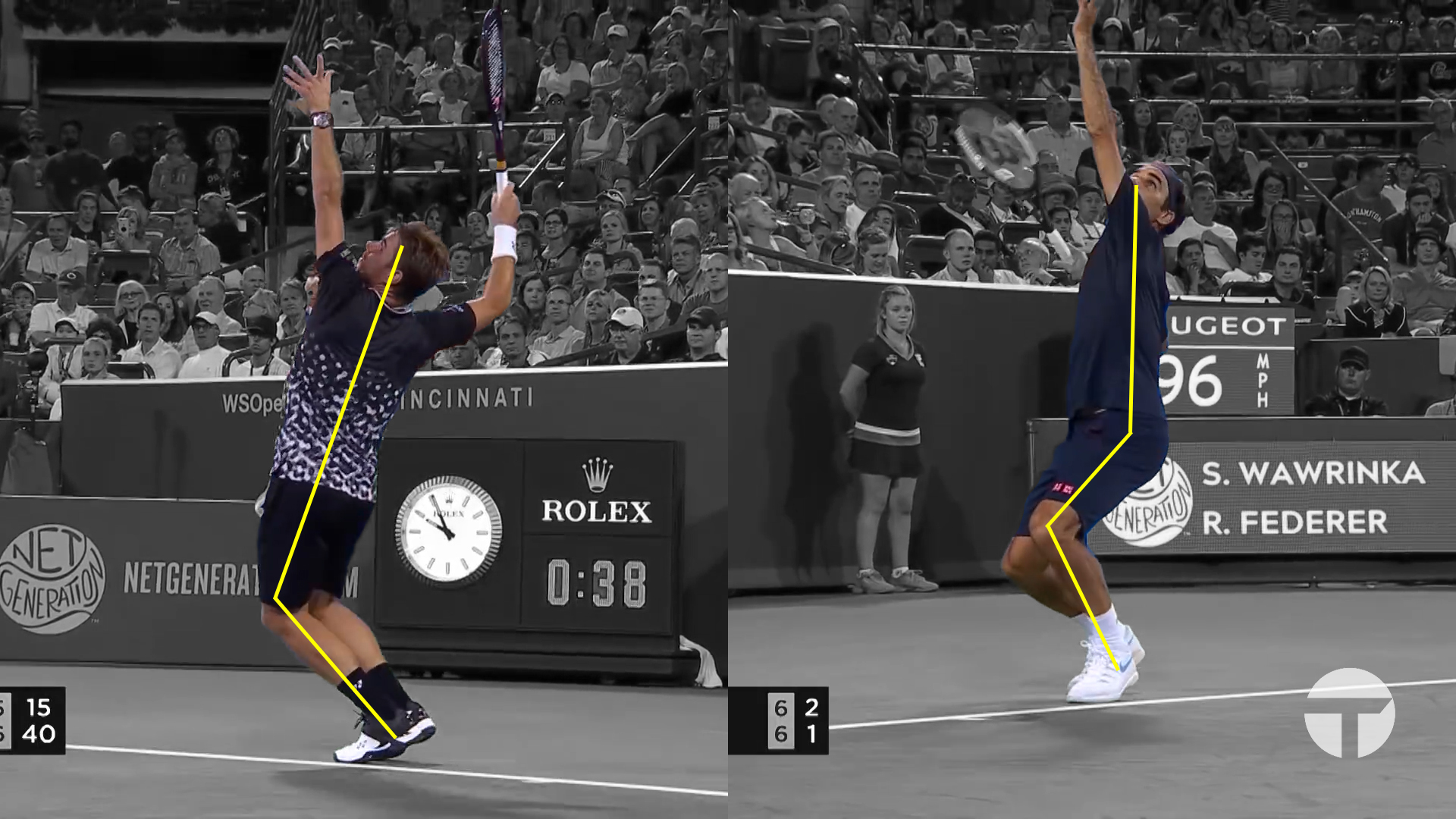

The Difference At Contact

All of this brings us to the height at contact. Nobody watching Wawrinka and Federer serve would claim that Wawrinka is putting less effort into the motion. If anything, the opposite would appear true. And yet, here is the difference between them at the point of contact.

This image is to scale. The difference in the height of their jumps for the serve is actually this large. Which brings us back to 4%. There are some other factors that impact first serve percentage. Technique, spin, neurological performance (targeting) are just a few of them.

Other aspects of Federer’s serve are undoubtedly superior to Wawrinka’s. However the single biggest impact on the difference in their first serve consistency is likely to be the difference in their jump. We are dealing with two elite tennis players – one arguably the greatest ever, and the other who has built a hall of fame resume in the toughest era in men’s tennis history. Both have amazing neurological performance, and both hit a heavy first serve. But Roger jumps significantly higher than Stan. This increased elevation at contact grants Federer better access to the box, which has a direct impact on first serve percentage.

Conclusion

It is clear that gaining more height at contact is beneficial to the serve. Increasing our leg strength and explosivity is one way we can increase that height. Improving our service technique is another. By adopting better elements of vertical jumping technique (such as greater knee bend, or more hip flexion) into our trophy position, we can bring our first serve percentage up considerably.

The challenge is doing so without compromising other elements of the serve. After all we still need to have the arms in positions that allow for good attack angles to the ball. There are significant benefits to having rotation of the trunk towards the back of the court. These are just some of the other things we need to incorporate. Finding the balance is part of the journey in progressing from mediocre to good, or good to great.

-

Serve Mechanics – Ball Toss (Part One)

Introduction

There is no scientific formula for the perfect serve. The serve is possibly the most complex biomechanical movement in tennis. When we consider that every individual comes to the table with their own unique functional movement patterns, the idea of ‘perfect’ quickly goes out the window. Two people of the same height may have different length arms, legs and torso. Athletes bring their own injury history to the table. Their range of motion will be different across various joints and in different directions. The short of it is no two people are identical in terms of their mobility and physical capacity.

While we might surrender the idea of a universally ‘perfect’ service motion, what we can do is identify the guiding principles that help people develop the best service motion for them. We begin by looking at the ball toss because the toss location influences what the underlying philosophy on what our serve will be. Perhaps no single aspect of a fully developed service motion is so variable and subject to so much debate. Poor toss placement limits our ability to hit different types of spin, to achieve disguise, and also limits the amount of energy we can reliably put into the ball. The toss is a boundary that will affect every other aspect of a service motion if done poorly.

Power And Consistency

Traditionally, for those of us who aren’t 6’9 serving has been considered a constant balancing act between power and consistency. This war between the two has largely come about due to misunderstandings on where the power in the serve comes from. It is this misunderstanding we aim to address (and hopefully correct) as we work through the various principles of a great service motion.

Power comes from two things – the speed of the racquet head at contact, and the amount of that energy that is transferred into the ball. The higher both of these numbers, the faster the serve will go. Consistency is more complex. It is affected by the repeatability of the motion itself, neurological ‘aiming’, and other things. Regardless, there is one simple concept that impacts consistency universally – the higher the point of contact, the higher the capacity for consistency with any given service motion. This last is the aspect we can impact with ball toss.

In summary, we want to get the racquet moving very quickly, we want to transfer as much energy as possible into the ball, and we want to do so as high above the ground as possible. What does this mean in terms of the ball toss?

What Do Elite Servers Do?

For this article we will look at the serves (specifically the tosses) of four players: Federer, Isner, Raonic, and Kyrgios. Each of them has a phenomenal serve. Importantly, we are dealing with players whose height ranges from 6’1 (Roger Federer) to 6’9 (John Isner). First we’ll take a look at what their toss is like at contact. Next we’ll put some numbers to what they are doing. Finally, we’ll talk about the why of it all. And why what you’ve always thought about ball tosses is probably wrong.

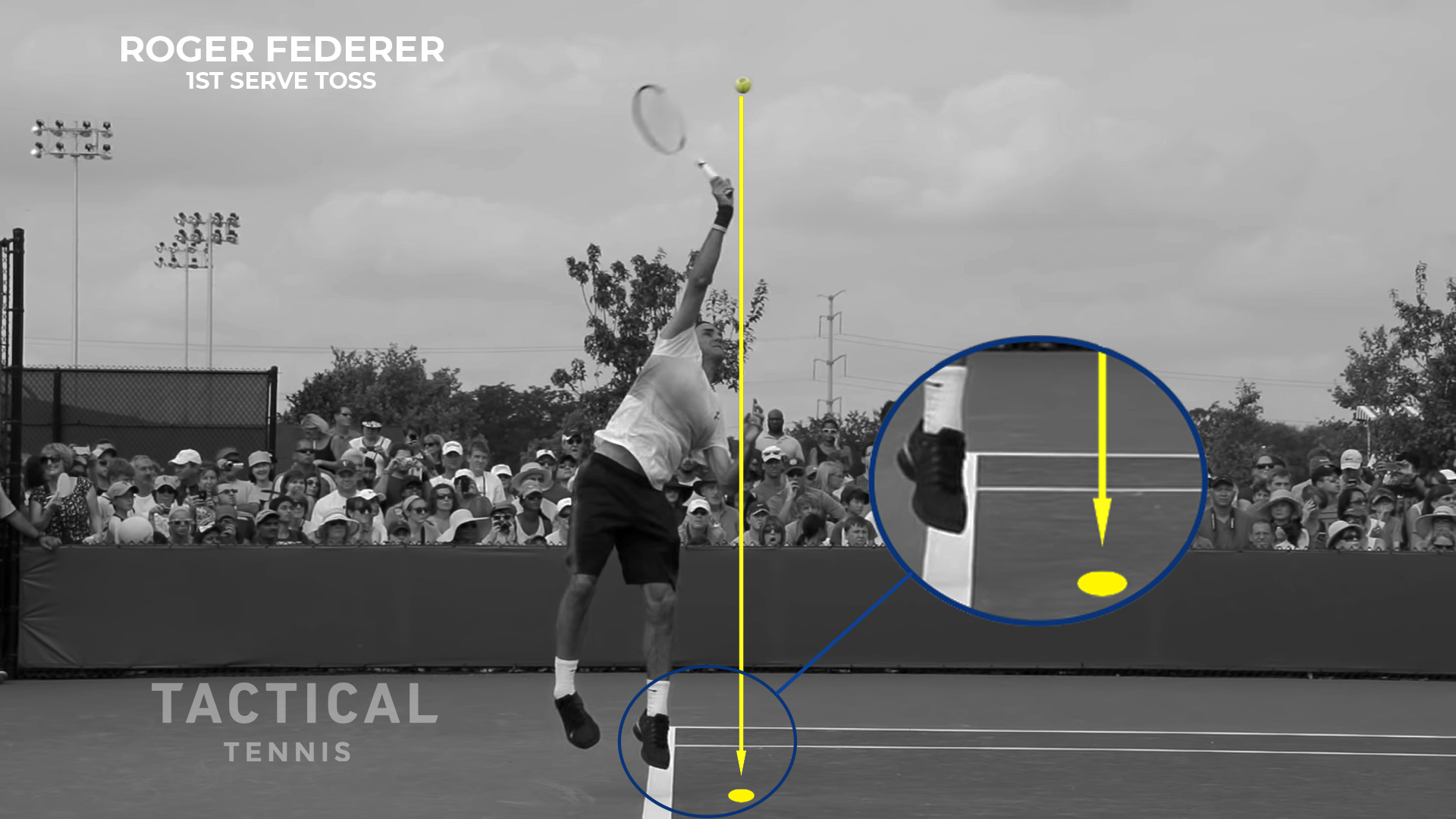

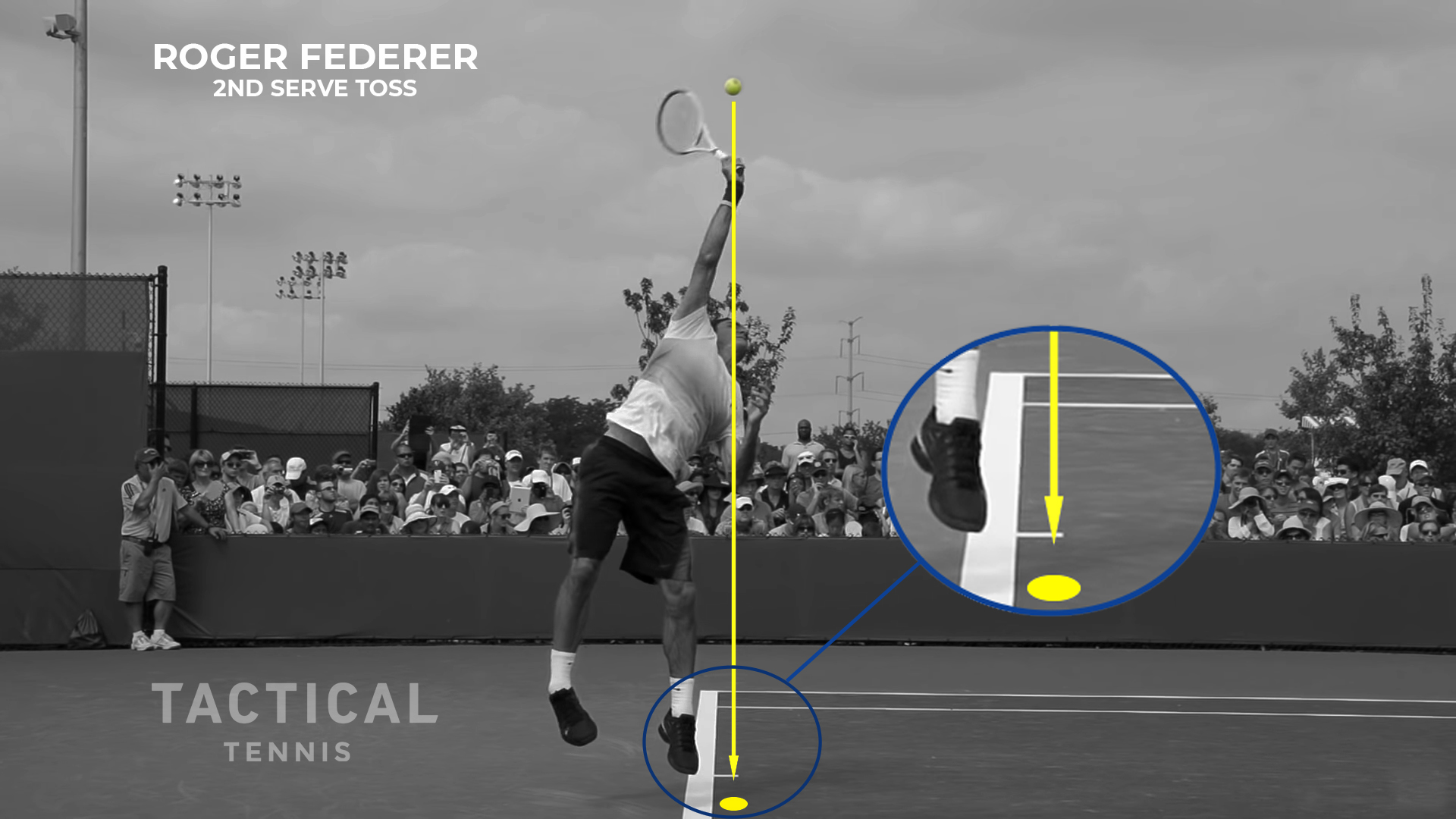

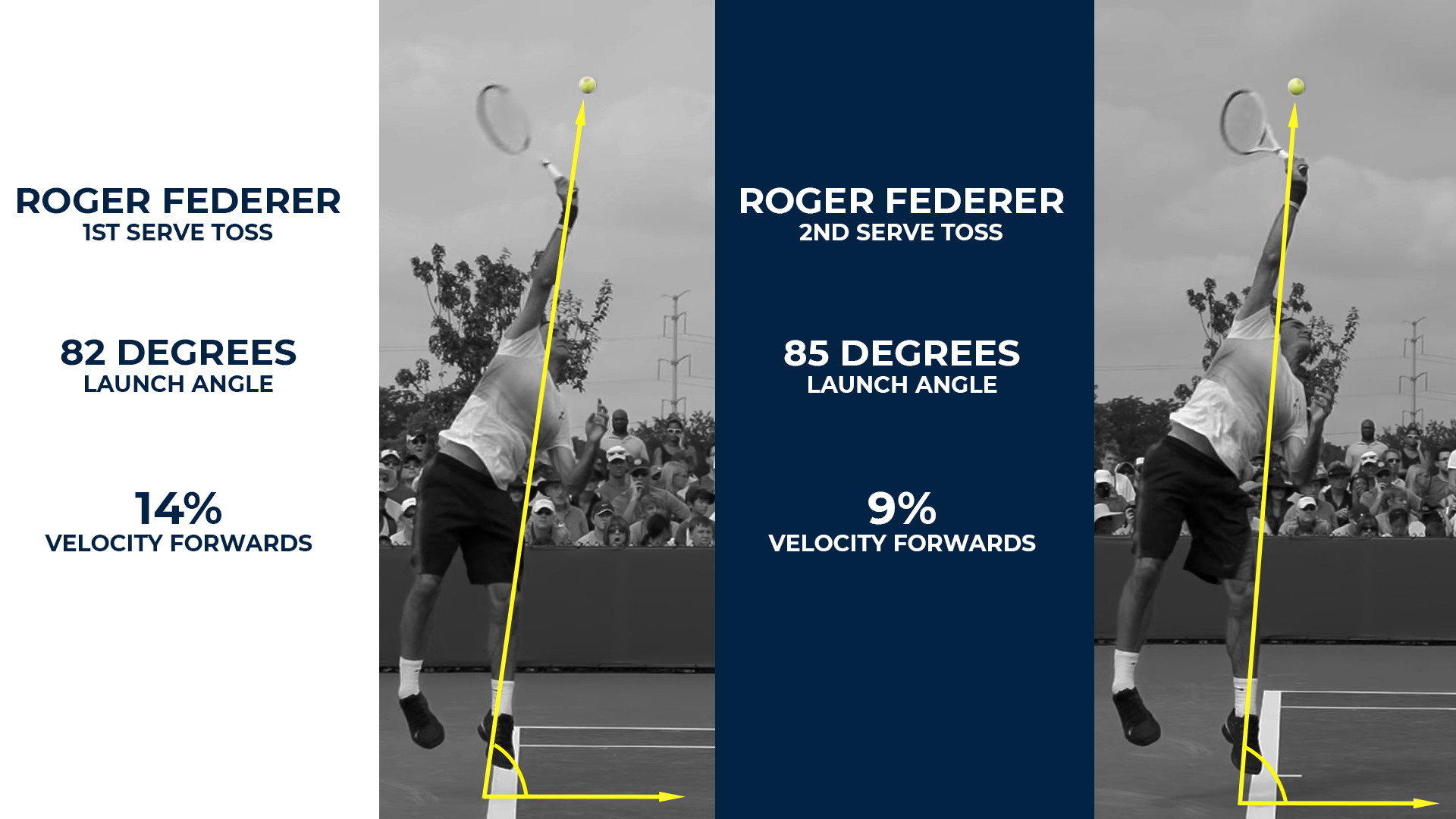

Federer is known for serving with both accuracy and disguise. What is often overlooked is his ‘flat’ serve clocks in at around 125 mph. Roger generates such easy power, which is a big part of why he is able to be so precise. At the point of contact, Federer’s toss is barely in front of him on the first serve. What about on the second serve?

We can see that Federer’s toss is even closer to the baseline on his kick serve than it was on his first serve. The angle of attack into the ball is different on this serve, in part due to the change in ball toss location.

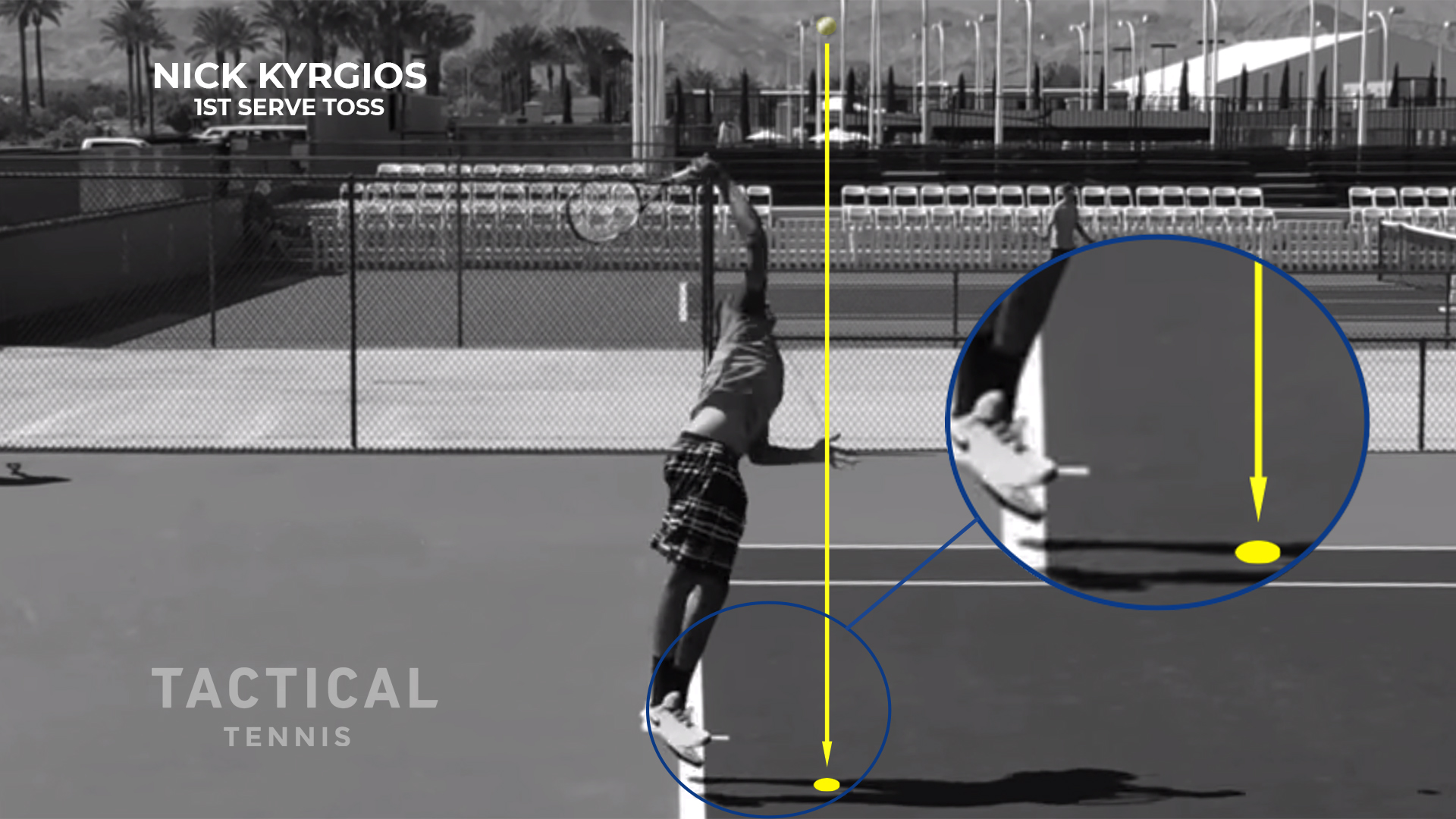

6’4 Nick Kyrgios tosses the ball slightly further into the court than Federer, but is also 3-4 inches taller. We can still see that the toss is far more upwards than it is outwards.

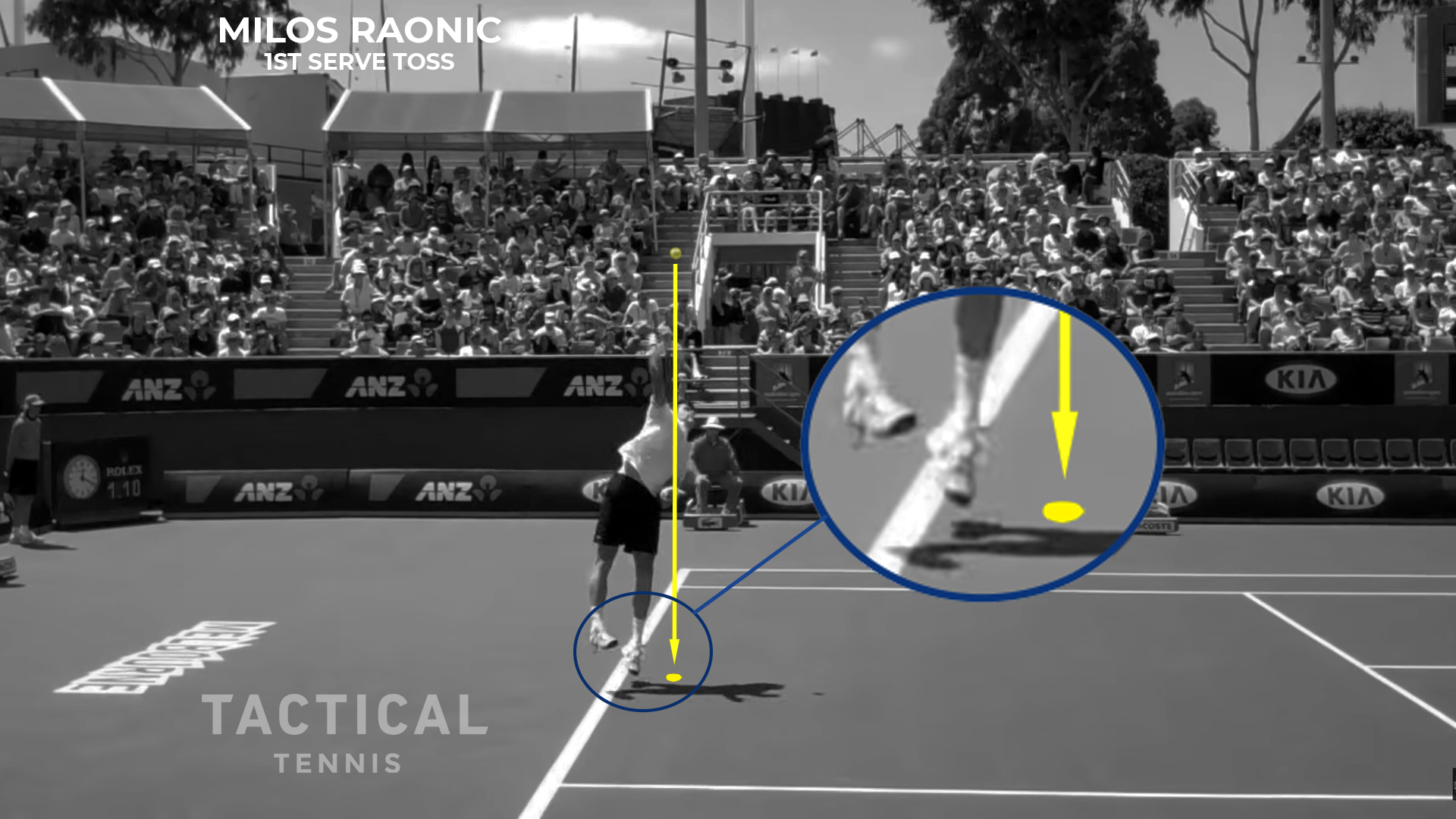

Roanic’s toss appears to be slightly closer to the baseline than Kyrgios’, yet slightly further out than Roger’s. At 6’5, he is the second-tallest of those whose serves we will be examining.

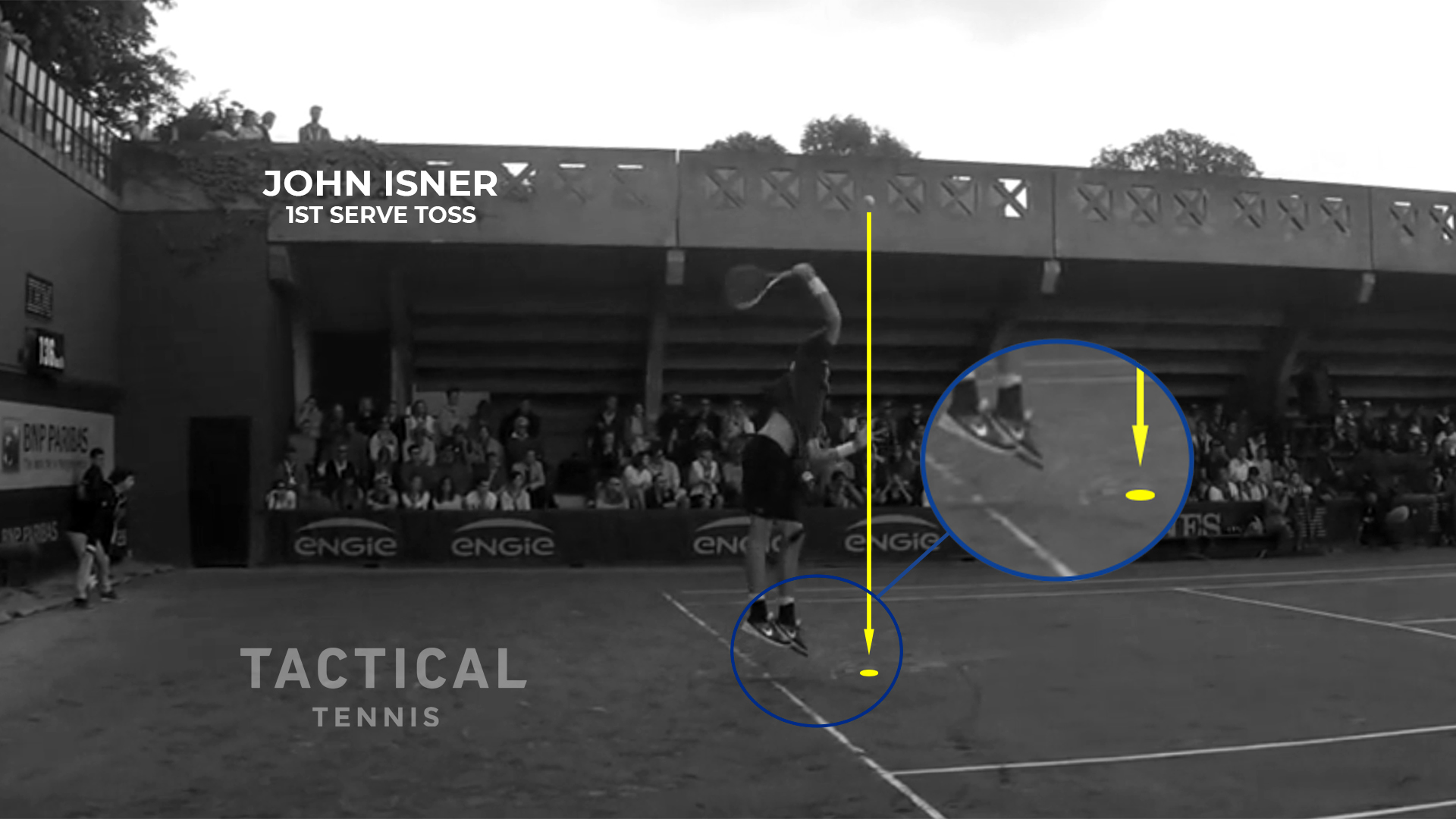

Last but certainly not least, we have John Isner. His toss is further into the court yet, but it is important to remember that he stands a towering 6’9!

Angles, Not Distance

Ultimately, the distances don’t really matter. Or rather, the distances only matter in the context of how high the point of contact is on the serve! As the contact point becomes higher and higher, it allows for more and more projection into the court towards the net. Let’s go back and check the angles on those serves that we already examined.

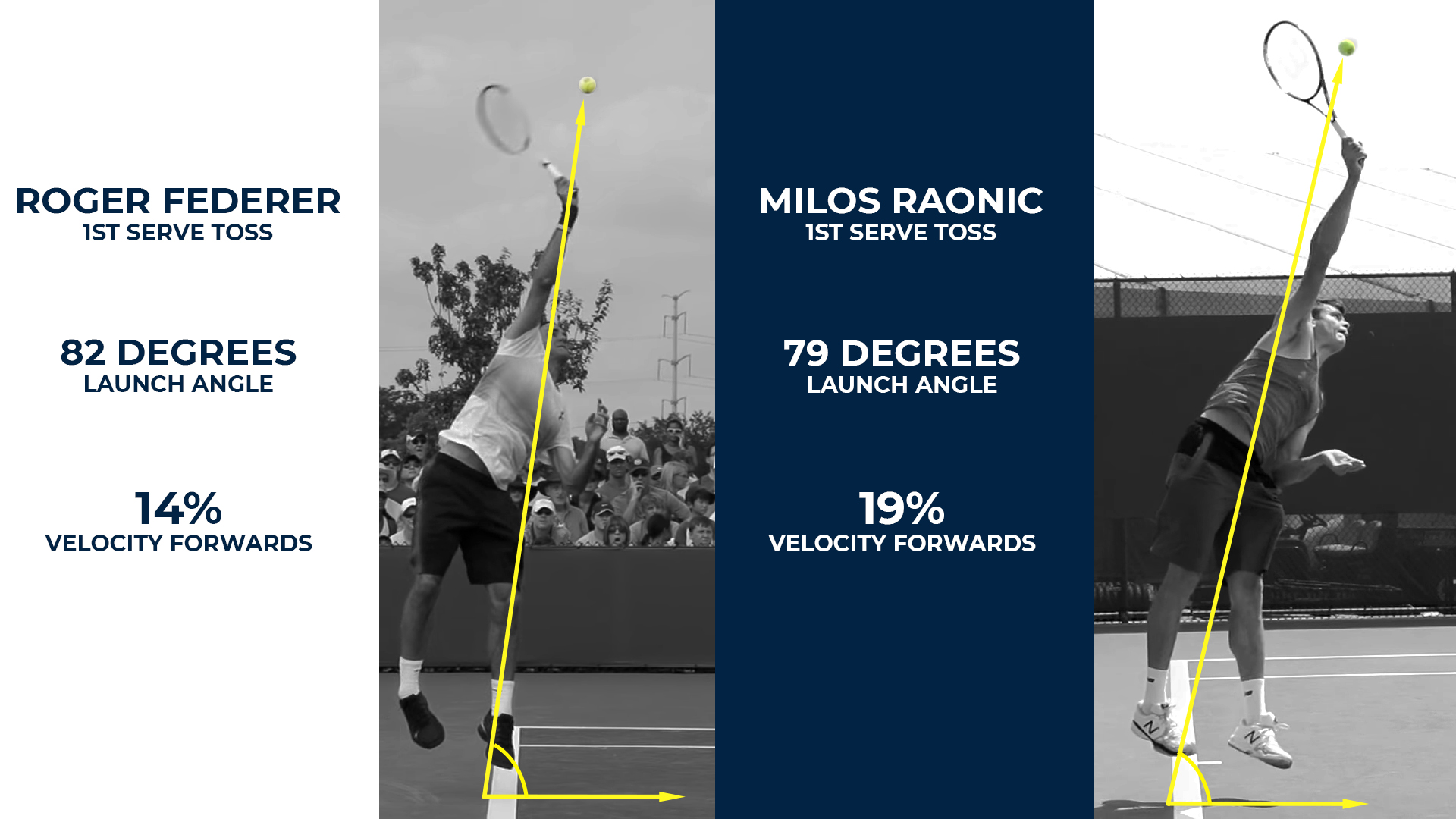

Federer is the most upright of the players that we’ll examine. On his first serve the ball is at roughly 82 degrees from his launch position on the baseline. As noted in the image, this means only 14% of the velocity from his jump is going ‘forward’ into the court. 99% of the velocity goes upwards (thanks to trigonometry, these two numbers don’t need to add up to 100%).

Raonic’s toss is at a slightly lower angle. His 79 degree launch angle means 19% of his jumping velocity is into the court (and 98% upwards). Give his 4″ height advantage over Federer, he can afford to surrender a small amount of height and toss the ball slightly further forwards

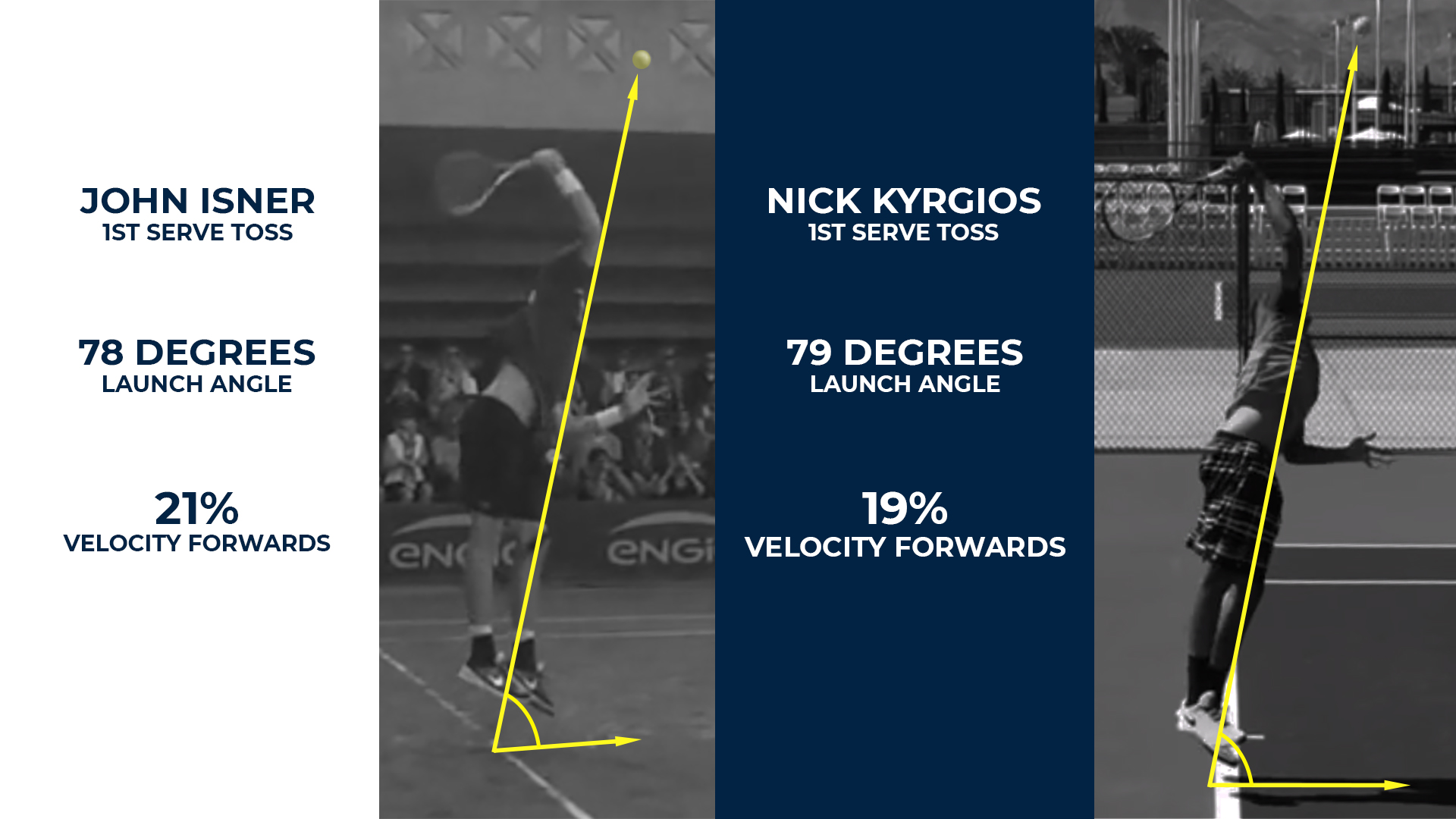

We see Isner and Kyrgios with almost identical launch angles. Isner’s 78 degrees nets him 21% of his jumping velocity forwards, which Kyrgios’ 79 degree launch angle matches Raonic’s and also puts around 19% forwards. It probably isn’t coincidence that three of the greatest servers in the history of the sport all have 78-79 degree angles for the point of contact on their first serve – regardless of their height. It might also not be coincidence that the only 6’1 server in the modern game to even come close to these three giants has a steeper angle at 82 degrees.

There is a critical idea here related to height, distance, and angle. A 6’9 player at 78 degrees (such as Isner) will inevitably make contact further into the court from a pure distance perspective than a 6’1 player with the same launch angle unless the 6’1 player jumps so high as to match the contact height of the taller player. This doesn’t mean tossing further into the court is better! It does mean we should focus on an optimal body position at contact, and use a toss that enables that. This angle is much more upright than most people realize. It is also possible that even the angles of Isner, Raonic, and Kyrgios might not be quite ideal!

Jumping Forward And Power (Math Time!)

The common dogma/myth in tennis serving is that we need to jump into the court for power. There is, as it turns out, some advantage to being closer to the net at the point of contact when we serve. However that advantage cannot come at the cost of decreased height at contact if we want to be an elite server. In truth, the idea that power comes from tossing the ball further into the court is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of where power actually comes from.

This is where we get to the math/physics portion. If we assume a player jumps 12 inches (30 cm) off the ground in their service motion, some good old fashioned math tells us they are traveling at around 2.5 m/s (roughly 5.5 mph). Now remember from above, the majority of this velocity is straight upwards – only a small portion is forwards into the court. At the peak of their jump, all of the server’s upwards velocity has halted (thanks gravity). Their forward momentum hasn’t stopped though. They are still moving into the court at around the same speed they were when they left the ground.

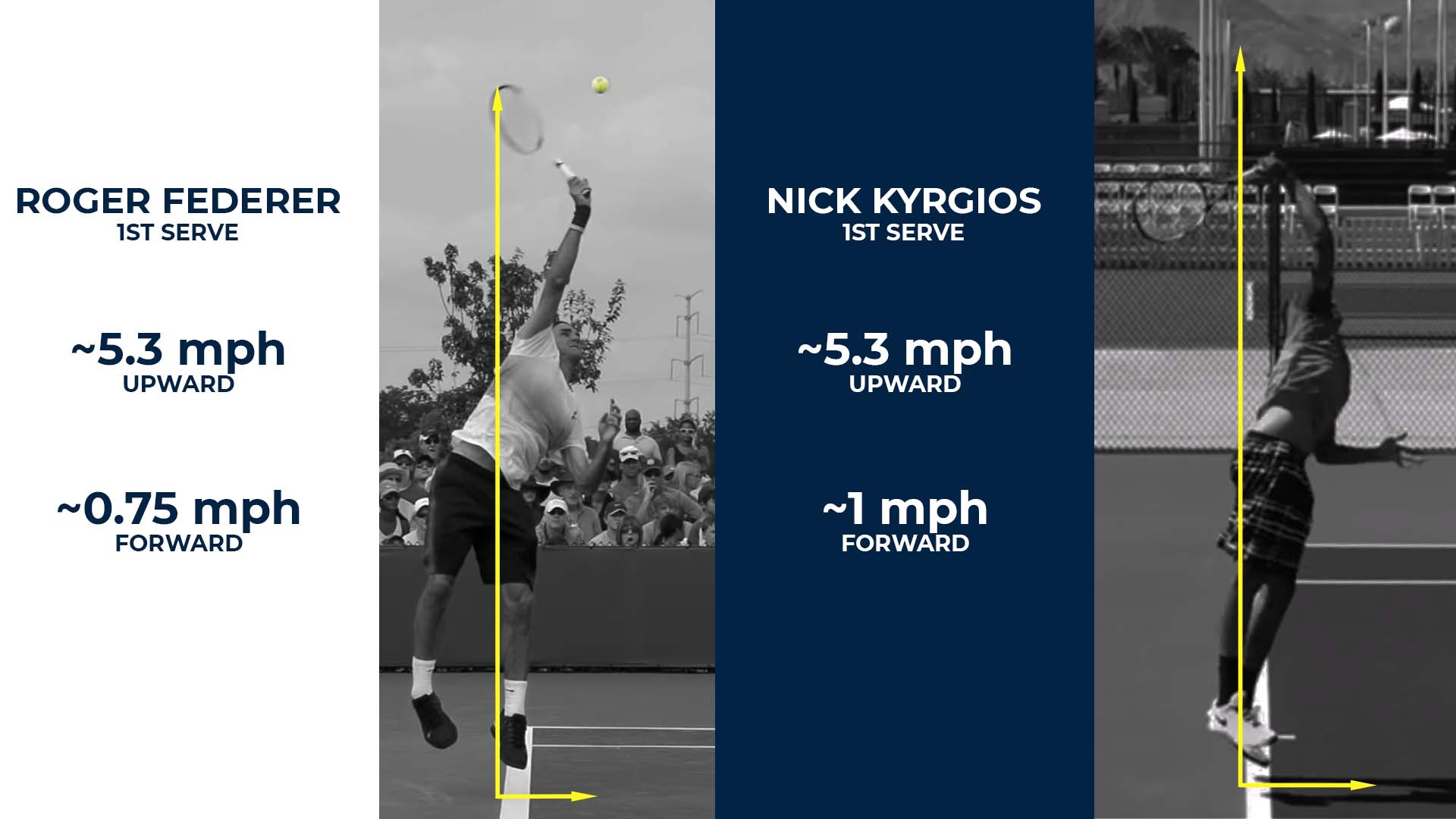

For Federer, this means his forward velocity on his jump is about 0.75 mph. For Nick Kyrgios, it’s 1 mph. To put that in perspect, the walking speed of an average sized adult is around 3 mph.

If jumping forward is so important for power, how does having your body moving at 1/3 of walking speed make a difference on a 130 mph serve? How could this 1 mph possibly matter?

The short answer is, of course, that it doesn’t matter at all.

Jump And Toss For Height (Not Power)

We can probably agree that making contact higher in the air is beneficial. If you had any doubts, consider that top three aces per match in ATP history are Reilly Opelka (6’11), Ivo Karlovic (6’10), and John Isner (6’9). That’s probably not a coincidence. We know that being higher at contact improves not only our consistency on the serve, but also our ability to serve aggressively. Conversely, the lower we are at contact, the less margin for error we have.

We’ve established that the jumping only adds approximately 1 mph of body momentum to the serve. This could potentially be increased by tossing further into the court. Increasing the toss angle to 65 degrees would double our forwards jumping speed to a massive 2 mph. Critically, doing so would decrease the height at contact by 12 inches! Does this seem like an equitable trade-off?

When it comes to the position of the toss relative to the baseline, the primary goal should be height, not forward momentum. It is true that we want the toss in front of our body, in order to be able to hit a biomechanically sound serve. But beyond a bare minimum of 4 to 12 inches (10-30 cm), tossing further forward decreases our serving effectiveness by reducing the height of the ball at contact.

Other Considerations

For someone who plays serve and volley tennis, there are other advantages to tossing the ball forward than adding a negligible amount of velocity. Landing 2 feet closer to the net puts one, well, 2 feet closer to the net. That can be the difference between playing a regular volley or a half-volley for the first follow-up shot after the serve. There is also the matter of having more forward momentum on landing. Being able to continue a forward motion gets one to the net more quickly than jumping completely vertically, landing, and then accelerating forwards.

These are very real considerations for a serve-and-volley player. The key point is understanding the trade-off that we are making if we choose to toss the ball further forward. Our serve will be less effective, but we get to the net a little more quickly.

First Serve versus Second Serve

The main difference between what most players hit for a first serve versus a second serve is the prioritizing of spin over velocity. This necessitates a difference in approach vectors of the racquet towards the ball. That is the trade-off when we consider kick serves over slice or ‘flat’ serves. It isn’t that Federer swings slower on his kick serve than his first serve. His goal is to put just as much energy into the ball. Rather, more of that energy goes into rotational energy (spin) instead of kinetic energy (velocity).

What does this look like in terms of toss position for Federer?

Federer has a steeper angle of approach to the second serve toss, which is placed slightly closer to him than the first serve toss. With spin being a huge focus, his goal is to put energy into the ball in a more upwards vector, driving huge rotation of the ball.

Access To The Ball

This brings to light the final, and important concept. Our toss doesn’t just change the way that we jump. The position of the ball relative to our body changes which parts of the ball we can make contact with. As a simple example, when we toss the ball in front of us on a serve we cannot make contact with the side of the ball closest to the net. The toss location (and the desire to hit it towards the net) preclude that.

When the ball is largely directly above us, we have the capacity to strike the ball in many different places. We get to approach the ball with the racquet from a lot of angles. As the toss gets further and further into the court, the parts of the ball we have access to become smaller and smaller. This limits our ability to impart different spins on the ball! This also reduces our ability to create uncertainty in the receiver. If we can only hit one type of spin due to our toss, then they have one less thing to worry about.

What About Power?

Players make contact around the peak of their jump. At that peak, they are not traveling upwards at all, and forwards only at a fraction of walking speed. This isn’t exactly a great way to add power!

So if power on the serve doesn’t come from the leg drive, where does it come from?

We will cover this in an upcoming article on the serve. If you want to get started on figuring it out yourself, read the article on Shapovalov’s jumping backhand.

In the next article, we will look at the second part of ball tossing. We now know we should toss it fairly close to the baseline, but where on the baseline relative to our body should it be?

Appendix

We calculated the jumping velocity using kinetics formulas, then confirmed the numbers with energy calculations as follows:

Kinetic Calculation

Velocity at peak of jump = 0

Acceleration = -9.8 m/s^2

Distance = 0.3 mVelocity = (Initial Velocity) + 2* (Acceleration)*(Distance)

0 m/s = (Initial Velocity) + 2* (-9.8 m/s^2) * (0.3 m)Initial Velocity = -2 * (-9.8 m/s^2) * (0.3 m)

Initial Velocity = 2.42 m/s (5.41 mph)

Energy Calculation

Potential Energy at peak of jump is equal to the Kinetic Energy at the beginning of jump.

Taking Federer as example:

mass = 85 kg

gravity = 9.8 m/s^2

height = 0.3 mP.E = mass*gravity*height

P.E = (85 kg) * (9.8 m/s^2) * (0.3 m)

P.E = 249.9 kgm^2/s^2

Kinetic Energy = 1/2 * (mass) * (velocity)^2

249.9 kgm^2/s^2 = 1/2 * (85 kg) * (velocity) ^2

velocity ^2 = 2*(249.9 kgm^2/s^2)/(85 kg)

velocity = 2.42 m/s

-

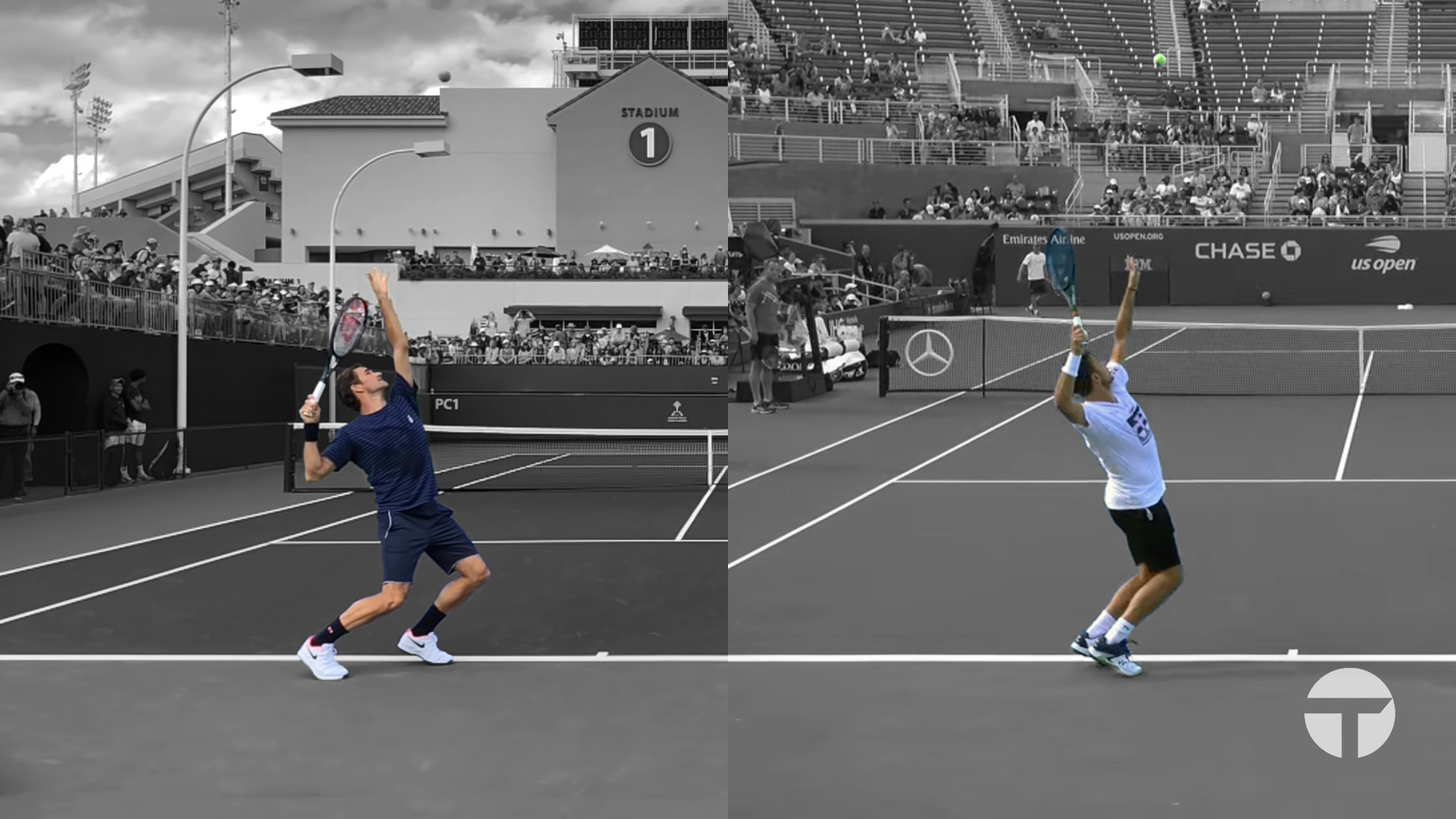

The Serve Part 2: Benoit Paire and the Power Of The Trophy Position

In Part 2 of Tactical Tennis’ series on the serve (go here for Part 1) we examine the service motion of Frenchman Benoit Paire. Paire is a name that is known mostly only to serious tennis fans – the 25 year old Frenchman has long been viewed as one of the potential up-and-comers to replace the current generation of greats. However Paire’s talent has largely failed to materialize actual meaningful results at the pinnacle of the game. We could look at a variety of reasons for this, but perhaps foremost is the fact that, for his height, Paire has what we can only generously term an exceedingly mediocre serve. At 6’5 Paire has the frame to possess one of the most fearsome serves in the sport. However a quick comparison with the Milos Raonic and Roger Federer shows that his serve is anything but:

First Serve % Ace % First Serve % Won Benoit Paire 51% 17% 72.54% Milos Raonic 62% 32.9% 82.3% Roger Federer 63% 17% 77.73% Now granted Raonic has the most fearsome serve in the game (yes, his aces serve far outstrips that of even 6’9 John Isner) he serves to show the potential that can be had from a 6’5 player with a good service motion. Throwing Federer in there is just rubbing salt in the wound – at 4 inches shorter Federer hits aces at the same rate as Paire but makes 12% more of his first serves!

What does this really tell us? In essence that there are some fundamental problems with Paire’s service motion! With his height he should either be putting far more first serves in play at his current ace rate, or hitting significantly more aces at his current first serve %. Or, as with Mr. Raonic, both. So we can look at these statistics and realize that Paire’s neither being overly cautious nor aggressive with his serve. This is not an issue of serving philosophy, but rather one of technique. So what is the problem with Paire’s serve?

The Importance Of the Trophy Position

If you’ve taken a tennis lesson from a half-decent pro that involved the serve you’ve probably heard of the ‘trophy position’. It is so called because if you’ve ever won or even seen a tennis trophy for a non-professional event there’s a very good chance it looked something like this:

Now the first question we ask is: why is this position so important? The answer is, unfortunately neither simple nor easy to convey in a single article. However if we can accept a few basic principles of tennis strokes perhaps we can sidestep some of the more detailed explanations. So let’s start with some concepts:

1) Long, smooth acceleration tends to be better controlled than short, violent acceleration

2) Rapid changes of direction of the racquet head do not lend themselves to long, smooth acceleration

3) Every position in a tennis stroke is path-dependent. Which is a scientific way of saying it doesn’t just matter that the body/racquet got there, but how it got there makes a difference

Keep these ideas in mind when we look at the following image:

In this image we have, from left to right, Benoit, Federer and Raonic all at a very similar stage of their service motion. Hopefully at a glance we can see that while Raonic and Federer have similar positions with their right arms, Paire’s serving arm is in a different location altogether. Whereas Federer and Raonic bring their left and arms up together in a somewhat synchronized fashion (the racquet arm coming up together with the tossing arm), Benoit lets his racquet arm lag behind, holding it down low near his waist while his tossing arm goes up. This has consequences for the rest of his motion, as we can see here:

We can see in this image all three players in the trophy position. Or rather, we can see two players in the trophy position and Paire approaching a trophy position. This is critical because at this point in the serve both Federer and Raonic are poised for their racquet head to drop down their back smoothly and to begin acceleration along that same plane up to the ball. Not so for Paire. His racquet is still trailing, and is not in line to drop down his back smoothly. Instead Paire most bring the racquet head up in line with his shoulders, then rapidly change its direction and pull it down his back to begin his attack on the ball. Now remember concept #2 from above? That rapid changes of direction do not lend themselves to smooth acceleration?

The problem is Paire is playing catchup because his arm lagged behind earlier in the stroke. As such he is rapidly transitioning through the natural power position that all great servers in the history of tennis have hit clearly and distinctly. Sampras, Ivanisevic, Krajicek, Becker, Philippoussis etc etc all had clearly recognizable and distinct trophy positions that are surprisingly identical despite other aspects of their motions being wildly different.

This is a problem I deal with sometimes in the college ranks, and almost invariably the culprits communicate that they feel like their motion is more powerful when they let their serving arm linger. The rapid and violent acceleration needed to catch up to their contact point gives them the illusion of power but in reality they are sacrificing control (and ironically often sacrificing power as well). In practice what we see is that servers who lag their serving arm typically have trouble hitting certain locations in the box, and their serve % is lower than it should be for their given height and serving philosophy.

Key Elements of the Trophy Position

Let’s not settle for just pointing out something that Paire does poorly – we can take this as an opportunity to highlight one of the absolute key positions in an effective service motion! So what are the key elements of the trophy position?

The High Elbow

Element #1 is what I’ll just call the ‘high elbow’. A common mistake at this point of the serve is for people to drop the elbow below the plane of the shoulders. You can see here with both Federer on the left and Sampras on the right that their elbow is an elevated position, either level with or slightly above the line of the shoulders. This is critical to allow good external rotation of the shoulder as the racquet drops down the back – lowering the elbow at this stage limits external rotation, limiting power while also introducing unnecessary movement into the motion.

Just to highlight this idea, here is Federer in external rotation. We can see that his elbow position relative to his shoulders is unchanged – it is a stable point of rotation as he drops the racquet down his back and begins to accelerate up to the ball.

Body Alignment

The second key element is the body alignment. It was rather tricky to find a good image to display this, but the one shared below should illustrate the point nicely:

What exactly do we mean by ‘body alignment’? If we look at Federer’s left shoulder, right shoulder, right elbow, right wrist and racquet head, they all lie on the same plane. You could almost imagine Federer as a mime, pretending to press his body up against an imaginary glass wall. Why is this alignment important? It allows Federer to accelerate his racquet down his back into external rotation of the right shoulder most efficiently (as mentioned above when comparing Paire’s serve to that of Federer and Roanic).

The Extended Left Arm

We don’t even need a new picture for this last one – the extended left arm. In the image above you can see Federer’s left arm is extended up high into the air, and remains there until relatively late in his service motion. A very common error among beginning and intermediate players (and even sometimes advanced ones) is a tendency to pull the left arm down prematurely. When this occurs, it drags the left shoulder with it, breaking the player’s posture and shortening their reach up to contact. They are both physically weaker, and also making contact lower which is a bad combination for good serving!

Conclusion

It’s time to bring the conversation back to Paire. His lack of a distinct trophy position isn’t the only thing wrong with his serve – he could use more leg drive for starters. However it is the single most obvious technical element that he could improve to quickly get results. We could forgive numbers like this from players in the 5’9-5’10 range, but even there are 5’10 players like Kohlschreiber who are simply better servers than Paire despite giving up 7 inches in height to the man. The good news for Paire is that this is a relatively simply fix. The bad news for Paire is that like so many other high level pros with glaring technical problems he will likely never fix it. For the rest of you however, don’t repeat his mistake! Focus on a good, strong trophy position in your service motion and your serve will improve!

-

Using The Wide Serve On The Deuce Court

When Roger Federer played Andy Murray in the Wimbledon final in 2012 he came onto the court with some very specific goals and strategies. One of these revolved around his serve location on the deuce court. Specifically he came out with the intent of serving an amazingly large percentage of his serves wide to the Murray forehand. This is nothing new – in his first round win against Paire in the Australian Open yesterday Federer put 13 serves out wide on the deuce court compared to just 2 down the middle. But it does beg the question: why does Federer put so many serves out into the forehand of his right-handed opponents on the deuce court? Today we’re going to break down exactly what Federer’s goal with this serve is, and show you how you can put it to good use in your own matches.

(more…)