-

Movement – The Universal Athletic Position

Introduction

Athletic movement is a critical difference maker in tennis performance. It is also one of the areas that players struggle to improve the most. Movement patterns are learned and habituated at a young age. Most players develop their physical capabilities (strength, explosiveness) as the pathway to better movement. This neglects the technique component. Understanding the universal athletic component is a critical piece of movement technique.

Tennis requires a greater adaptability in movement than almost any other sport. A tennis player must be able to react explosively in all directions. While other sports also have this requirement, few demand this capacity in such a wide variety of circumstances.

For reactive movement in tennis, only the return of serve offers us an opportunity to reset. During a point we must constantly adapt our positioning, and the demands of the movement are changing.

As such, it becomes important to be guided by principles rather than rules. Understanding the essence of good movement gives us the ability to adapt our movement to the situation in front of us. What constitutes a perfect split step changes depending on where in the court we stand and our direction of travel.

Ultimately we are guided by three key needs:

1. Balance

2. Explosiveness

3. DirectionalityThe Universal Athletic Position

All movement begins somewhere. The position that we begin from influences the movement that follows. The better the starting position, the better the potential for the movement. Our starting position should allow us to be balanced, to generate power efficiently, and to move athletically in all directions.

Enter the Universal Athletic Position.

The Universal Athletic Position (UAP) is so named because it is the most common position in sports. While there are sports that don’t feature the UAP at all, most land-based sports feature some version of it in at least some aspects of the sport.

We don’t train and use the UAP because it’s in most sports though. It is in most sports because it is the most efficient stance to be able to react explosively in all directions. That’s what makes it universal. More specialized sports that feature limited dimensions of movement will tend not to feature the UAP. However sports that require reaction in multiple axis of movement (baseball, tennis, basketball, soccer, cricket, among others) all see usage of the UAP at the highest levels.

How does it address our three primary needs?

Balance

Balance and stability go hand in hand. The more stable a stance, the less athleticism required to remain balanced in it. An athlete standing on one leg on an uneven surface faces greater challenges than one with a wide stance on a flat surface.

Primary things to note here are stance width, posture, and weight distribution. Generally, the wider the stance, the more stable it becomes. Past a certain point that stability becomes counterproductive. An athlete in the splits will not fall over, but also cannot move very quickly. We should aim for a stance wide enough to provide stability (heels outside the hips) without compromising movement (narrow enough we can comfortably bend at the ankles, knees, and hips).

Good posture doesn’t always mean standing upright. It does mean good spinal alignment. Across sports we see great movers keeping their spine erect even as they have flexion in other joints.

Finally weight distribution. We should strive to have as much of our foot in contact with the ground as possible when our direction of travel is uncertain. Different movement directions require applying force to the ground through different parts of our feet. If an athlete is on their toes, they cannot utilize their heels for movement without first putting their heels down – costing valuable time.

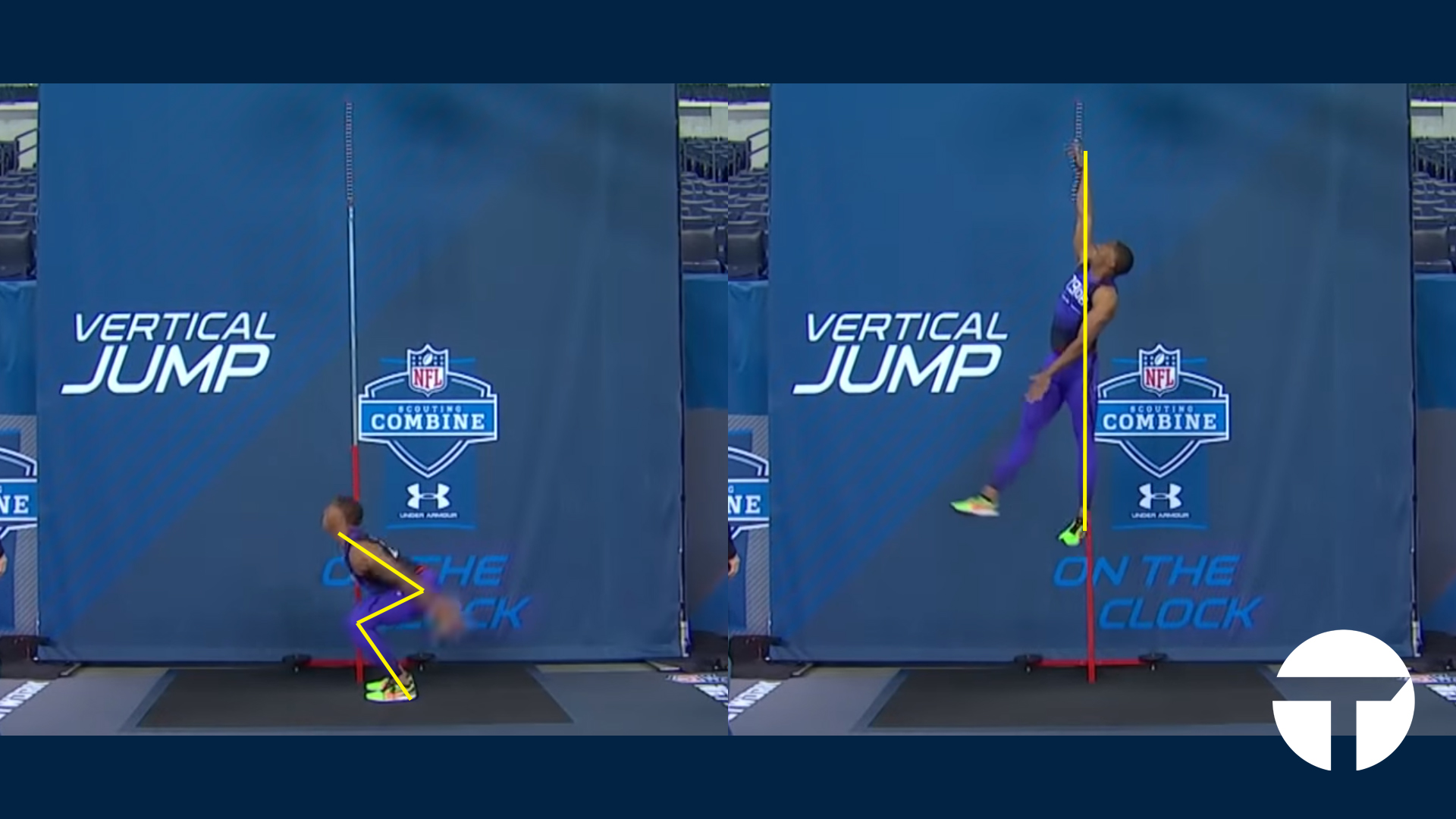

Explosiveness

If we consider peak explosive movement from a stationary position, we can take cues from great jumpers. There is a significant overlap in the muscles used for a standing jump and those required for explosive movement laterally, forwards, or backwards.

Byron Jones set an NFL combine record for the standing jump. His goal (and that of any great jumper) is to recruit as many useful muscles as possible towards upwards propulsion. We can see he engages flexion at the ankles, knees and hips. This allows him to use all of the powerful muscles involved in extending those joints to launch himself upwards.

We want to follow a similar path. A good Universal Athletic Position will feature the same patterns of flexion, just to smaller degrees. We should have bends at the ankles, knees and hips to utilize our quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves to maximum effect. Where a tennis player differs from a great jumper is in the amount of flexion and the width of the stance. A tennis player must compromise their potential jump height to allow for the third criteria: directionality.

Directionality

All of that force we generate is useless if we cannot direct it in the appropriate direction. Thankfully, there is a large overlap between the demands for balance and those of directionality. As our stance narrows it doesn’t simply make balance more challenging – it limits our ability to apply force in any direction other than upwards. Widening our stance to outside of our hips lets us use a combination of extension, abduction, and adduction across our two legs to move forwards, laterally, or backwards.

Additionally we can manipulate our weight distribution to allow even more direction of our generated force. An elite athlete will initiate a controlled fall to align their body better with their direction of travel. In a wider stance, lifting our left foot and allowing a degree of falling to the left allows us to better drive force in that direction.

Putting It All Together

This brings us to the finished product. A tennis stance where our feet are wider than our hips without limiting hip and knee flexion. Where we engage flexion at the ankles, knees, and hips for maximum force production. Where we keep good posture, to allow better control of our balance.

In highly contested points, a player might only attain a complete Universal Athletic Position once (as the returner) or possibly not at all (as the server). However great tennis athletes are always moving towards a Universal Athletic Position. They will obtain (or retain) as much of it as possible even as they move dynamically around the court.

When we understand the principles behind a position rather, then we can strive towards those principles. This helps guide our movement in non-ideal situations. We can move away from a binary way of thinking about movement technique (either you reached the position or you didn’t) to something more sophisticated (I retained as much of an ideal position as possible).

This is a path to better movement, and better tennis.

For more content follow us on instagram, facebook, and tiktok!

-

How Cilic Won The U.S Open

Enough time has passed now since Cilic’s US Open victory to put his win in perspective. But before we can answer some of the pressing questions such as “Is Cilic a one-slam wonder?” it’s worth taking some time to look at exactly how he was able to win his maiden Slam in the first place. We’ll take a quick look at his year leading up to the tournament, his run through the draw and then a more in-depth analysis of his wins over Berdych, Federer and Nishikori.

Cilic’s 2014

There were no early indications from Cilic that he would break the stranglehold of the Big Four in 2014. Cilic came into 2014 after serving a 4 month suspension for a positive drug test (for the stimulant Nikethamide that was in glucose tablets he consuemed). He opened the year with a quarter-final loss in Brisbane to Nishikori, the man he would beat in the finals at Flushing Meadows. After second-round losses at Sydney and the Australian Open, Cilic made three straight finals in Zagreb, Rotterdam and Delray Beach, taking two titles in the process.

This brief flash of brilliance would fade into a string of early exits across the summer until a quarter-final showing at Wimbledon where Marin lost to Djokovic in five sets. Another early loss at Umag in Croatia to Tommy Robredo was followed by R16 defeats at the hands of Federer and Wawrinka in the US Open lead-up events in Toronto and Cincinnati. In all it was a solid but uninspired year coming into the tournament, and generally Cilic was playing at a level below that of his previous career peak of #9 back in 2010.

The Draw Through The Quarterfinals

Cilic’s US Open draw was kind. He opened his bid for the tournament against an out-of-form Marcos Baghdatis who retired half-way through the first set. Next he faced 163 ranked qualifier Ilya Marchenko whom he summarily dispatched in three surprisingly close sets. This win brought Marin face-to-face with his first real test of the tournament, Kevin Anderson. The big-serving South African proved a stern test that Cilic navigated with a tough four-set victory. Next for Cilic was Giles Simon, a counter-punching Frenchman whom Cilic had never defeated in four previous meetings. His five set win here was the tipping point of the tournament for Cilic, for as we’ll see the home stretch proved to be far easier in reality than it looked to be on paper.

Cilic vs Berdych

This match had all the makings of a dramatic slug-fest. Although Berdych lead their head-to-head 3-1 on hard courts, they were 4-4 overall. Both players possess big serves backed up with powerful groundstrokes off both sides. At their meeting just a few weeks prior at Wimbledon, Cilic had prevailed 7-6, 6-4, 7-6 – a tight straight sets affair. Berdych had taken the meeting before that on hard courts at Rotterdam. In short the signs were there for a close affair that could almost be decided by a coin toss.

It turned out to be anti-climatic in almost every regard. To say that Berdych came out looking flat would be an understatement. The opening set he struggled to put balls in play, and the 6-2 scoreline was flattering given his level of play. He didn’t look remotely competitive. Cilic snagged an early break in the second set and rode it out as Berdych slowly came alive. In the third set Berdych went up an early break but Cilic earned it back and they served their way into a tie-breaker which Cilic took after stringing together the last three points in a row.

Cilic wins 6-2, 6-4, 7-6 (7-4). It was a classic example of a slow start from Berdych, and although we saw him raise his level as the match progressed he had only come back from two-sets-down twice previously in his career. Once Cilic took the second set the writing was on the wall.

Cilic vs Federer

The Cilic-Federer semi-final looked to be a far more intriguing matchup. Federer has a long history of blunting the power of one-dimensional ‘big men’ and the general wisdom was that provided he had the legs after his five-set win over Monfils Federer should be able to wear Cilic down. Heading into the match Federer was 5-0 against Cilic and Federer’s summer form had been solid if not good. So what happened?

I had most of an article written about this match alone before deciding too much time had passed to make it worth posting. So, here’s the short version: Federer was a step slow and Cilic took time away. That Federer was fatigued coming into the match was both obvious and somewhat expected. Watching the points play out it was striking how many times Federer made it to a fairly routine defensive shot and failed to put the ball back in play. Where the Swiss would normally extend points effortlessly he was making (admittedly forced) errors at a rate that was unusual.

But this wasn’t just a match that Federer gave away. Cilic did everything he needed to. Although his first serve percentage wasn’t stellar (56%), Cilic served big when he needed to. Virtually every time Federer started to catch the scent of a break on the wind, Cilic would drop a couple of bombs and come out of his service games smelling like roses. Likewise Cilic kept the pressure up. One of the few ways to get to Federer is to rush him (which is difficult to do). Cilic brought pace off the ground, hit through the court and generally didn’t give Federer a chance to settle into groundstroke rallies. And finally he stayed the course. Just when Federer was looking like getting a foothold in the match, Cilic kept on him and pounced the moment Federer slipped.

In all the match was a disappointment in terms of the quality of tennis, but it was an interesting tactical battle nonetheless. Federer’s efforts to extend points and stay out on the court were rebuffed by the big hitting Cilic and he came through the match without a serious hiccup. Would the outcome have been different if Federer had been fresher? Probably, but that’s the joys of Grand Slam tennis. Your job is to win the tournament and that means not just winning each match, but doing so in a fashion that gives you a chance at winning the next one. In that regard Federer failed and Cilic succeeded and it takes nothing away from Cilic’s achievement that Federer looked fatigued.

Cilic vs Nishikori

In some ways this was a similar matchup for Cilic as he had with Federer. Neither Federer nor Nishikori had real hopes to outhit Cilic, and their game plans of necessity more revolved around extending rallies, keeping Cilic out on the court and working the point until they had the advantage. The complexities came down to the differences between Federer’s and Nishikori’s games. Whereas Federer’s forehand is generally a much more varied and potent weapon than Nishikori’s, Nishikori has a much more reliable backhand. As such Cilic didn’t have the same safe place to go on the court against Nishikori that he did against Federer (not that he really needed it much against Federer as it turned out). Against Nishikori Cilic would have to have a more balanced offense.

As it turned out the brutal path Nishikori faced to the final made much of it a moot point. After five set battles with Roanic and Wawrinka, and then a draining four set win over Djokovic, Nishikori clearly had little left in the tank. Like Federer he was a step slow and against the big-hitting Cilic that was never going to get the job done. Cilic managed to play a tidy match, in much the same way as he had against Berdych and Federer and that proved enough. It was, again, a disappointing match in terms of the quality of tennis. To many observers it may have seemed an overwhelming performance of firepower from Cilic, but the reality is that he was never forced to play great tennis.

In Summary

Not all Grand Slam championship wins are equal. Had Nishikori prevailed it would have undoubtedly been a more impressive performance than Cilic’s given Nishikori’s significantly tougher draw. However that’s the nature of tennis tournaments – you don’t get the draw you want, you get the draw you get. Cilic did everything that was required of him to win the tournament. In this case, it proved to be a rather disappointing home stretch as in none of his last three matches did he have to play great tennis. Good was good enough and that’s what Cilic did. It would have been nice to see Berdych bring the focus, or Federer/Nishikori the energy to be able to truly push Cilic from the quarter-finals onwards.

This is not to cheapen Cilic’s win. It may well be that Cilic was in a place physically and mentally to sustain great tennis over the final three matches of the tournament but we’ll never know. It is hardly his fault that none of his final three opponents was up to the task of actually making him do that. Regardless of how those matches played out, Cilic is the 2014 US Open men’s singles champion and it will be interesting to see how he handles the heightened expectations moving forward. the early bet is that he is a one-slam wonder – the product of a hot streak combined with a lucky draw. Whether or not this is true time will tell.

-

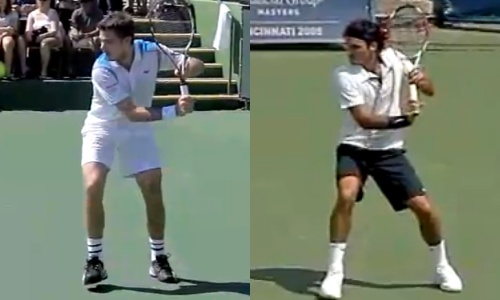

The Four Horsemen – The Backhands of Federer, Gasquet, Wawrinka and Almagro

Today we’re going to look at one-handed backhands. Specifically, the best four one-handed backhands in the world – those of Federer, Gasquet, Wawrinka and Almagro. Tommy Haas fans don’t despair – he certainly belongs in the conversation but as of the time of writing these four gentlemen are the highest ranked players with one-handed backhands and certainly all four have beautiful strokes in their own right. Purists of the game certainly decry the lack of one-handed backhands in tennis today, but let’s not plan funeral services just yet. With three of the top ten players in the world sporting one-handers rumors of its demise are greatly exaggerated! The point of today’s article is really two-fold: 1) to give people a better understanding of the key positions in a classic one-handed backhand and 2) to hopefully point out the subtle differences in the stroke of these four players so we can understand why they have different outcomes on the court. So without further ado, let’s dive right in.

Overview

Before we get too much into the technical aspects of the stroke, let’s establish a couple of ideas regarding the four backhands we will examine. Each of these four have a reputation that differs slightly from the others and covers a spectrum. Almagro hits a comparatively flat, extremely powerful driving ball with little variation. Wawrinka’s one-hander is slightly heavier, and more steady than Almagro’s. Federer generally hits a heavier spin ball with less pace than Almagro or Wawrinka, and his backhand is also more prone to go ‘off the rails’. Then there is Gasquet, who has probably the highest ‘top end’ of the four with the ability to hit pretty much everything with it – he can drive the ball with great pace, he can hit incredible spin for a one-hander, and everything in-between. So let’s take a look at the strokes and see what makes them tick. Note that there are subtle differences in each of the four shots these photos are taken from – we couldn’t exactly get Gasquet, Federer, Almagro and Wawrinka out on court with the ball machine for an hour to get photos of them hitting identical shots off the same ball. So bear that in mind as we look at the images.

The Chamber

The preparation phase of any stroke is, as the name suggests, the setup period. This is where the player puts the pieces in place for the kinetic chain that will soon be initiated. The preparation phase finishes in what I like to call the ‘chamber’ – where everything is prepared and ready to fire.

A couple of things to notice quickly here about the differences in their chamber positions. First of all, Gasquet has a more exaggerated wrist position – his wrist is rotated further up towards his forearm than Almagro’s. This opens the racket face up more, and together with the increased tilt in the racket head will provide for a more whip-like motion through the backswing generating more spin. Gasquet and Almagro both have relatively high hand positions in this frame.

It is a little uncanny just how identical Wawrinka and Federer’s positions are at this point in the swing. Note the relatively upright racket position standing almost perpendicular to the ground. Both Federer and Wawrinka’s rackets are more upright at this stage, whereas Gasquet and Almagro have laid the racket head back slightly. The two Swiss men also hold their forearms essentially parallel to the ground, with the right hand slung lower than Almagro and Gasquet. All four players have a good positive shoulder turn, have the left hand holding the throat of the racket for more positive racket control, and are looking to hit from a neutral or slightly closed stance.

The Bottom

From the chamber position the one-handed backhand will feature a dropping of the racket head as a part of the acceleration towards contact. This dropping of the racket head is critical for generating the topspin needed to hit the ball with real velocity and keep it in play.

Here we can see both players have extended their arm to either straight (Almagro) or a micro-bend (Gasquet) as they dropped the racket head down. Notice the upright position of the torso for both players, even though Gasquet is lunging for his shot in a wider hitting stance. Almagro releases the frame with the left hand a little earlier than Gasquet, but this shouldn’t have any real impact on the outcome of the swing.

In this frame we can see Federer start to differ from the others slightly. First, note the greater bend in the arm compared to Wawrinka. Secondly we can see that Federer has drawn the racket further around his body rotationally, with the string-bed essentially pointing to the back of the court. In comparison Wawrinka and Almagro have angled theirs back a moderate amount while Gasquet has angled his only slightly. This means that Federer will ‘uncoil’ through his swing more than the others – his backhand will swing out from his body with more of an arc compared with a more linear swing from the other three. This greater swing curvature does complicate the timing slightly. Add in the increased bend in the arm (something which we notice will disappear later in the swing) and we begin to see why Federer’s backhand is generally less steady in many respects (Almagro’s poor decision-making notwithstanding). His mechanics require more precise timing than the other three, and hence he is apt to mis-hit more balls than them. The final thing to note is how the hips for all four players have essentially not moved from the previous stage in the chamber position.

The Contact Point

What might leap out at you first from this image is just how far in front of the body Gasquet is making contact with the ball. The second thing you might note is just how extreme his grip is compared to Almagro. He is almost past an eastern backhand grip, with the first knuckle of his index finger approaching the back-diagonal bevel of his grip. This grip is part of the reason why Gasquet is able to attack the high ball so well off his backhand side (something he does better than the other three). However it also forces his hips into a slightly more open position at contact, something we can see in the picture also. Speaking of hips, Almagro’s have opened slightly from the chamber and dropped positions.

In the previous frame we had pointed out the greater bend in Federer’s arm compared to the other three. Now at contact we can see that his arm, like all the others’, is straight. Federer also is making contact very far out in front of the body, although this is partly due to the fact that the ball he is hitting is higher than that of Wawrinka’s. It is surprising to see just how much Wawrinka has opened up in this frame – although we expect some opening of the hips to allow the arm to come through and the shoulders to clear, Wawrinka’s position is slightly exaggerated compared to the others. One common theme to note is the position of the left hand – all four player release their left hand from the racket throat close to their own left hip – a position their hand now stays in until after contact. This is to help anchor the shoulders in position and prevent opening up too much too early.

Much is often made by commentators about the way that Federer seemingly tracks the ball until it makes contact with the strings. Meanwhile scientists claim that the moment of impact happens so quickly that it cannot be captured by the naked eye. What the image above seems to suggest however is that Federer truly isn’t seeing the contact itself in the way that people think. What is critical is the stability of the head during the contact phase. Most players will lift their head to track the ball off the strings but Federer’s gaze lingers considerably longer. This keeps his head locked in place, a positive thing for any budding tennis players to copy.

Follow-Through

The arm positions of both players here are remarkably similar. The critical difference to notice again is the increased openness of Gasquet’s hips – again likely due to the more extreme grip he uses. In contrast Almagro has actually moved his left hand backwards slightly, which helps to keep the shoulders from opening too much too quickly.

It is a shame that the video for Wawrinka cut off his racket here, but we can see he has a slightly more open position compared to Federer or Almagro. Both players have straight arms, and whereas Wawrinka has begun to raise his gaze and hence his head, Federer’s vision is still locked in on the same space it was a moment before. Notice how Federer’s left leg is kicked backwards, somewhat similar to that of a bowler (ten pin) after releasing the ball. This is designed to serve as a counter-weight to the arm and racket rotating in the opposite direction and helps anchor the hips in place to stop them from opening.

Five Points To Take Away

1) Get the racket up during your backswing. All four players hit an almost identical chamber position.

2) Locking the arm out earlier is a good thing. We can see Federer is late to straight his out and it simply adds one more complication to the timing of the stroke. It also creates a slightly less consistent stroke path compared to the other three.

3) Keep the hips closed until right before contact, and only open them a little. Players can use a countering motion with their left hand and left foot to help keep hips and shoulders closed.

4) Get the ball out in front. The higher the ball is, the further in front you need to catch it.

5) The differences are small. While we don’t know what shot each player hit off the images in question (heavy topspin vs flat, passing shot vs lob etc etc) we can say with certainty that the differences between all four backhands are subtle. Picking them out in real-time with the naked eye becomes extremely difficult if not impossible.

To be honest before starting this article I expected greater visual differences between the four of them. It’s clear that most of the differences in their hitting styles are more a matter of choice than technical limitation. Gasquet’s grip and consequent opening of the hips and shoulders at contact is the most significant difference between them all. Almagro and Wawrinka probably hit harder and flatter, not because they can’t hit more topspin, but because neither moves as well as Federer and hence must keep the initiative off that side. Federer prefers a heavier, more rolling ball because it buys him time to run around his backhand and hit forehands. Gasquet can do it all because he is a phenomenally talented ball striker with a technically fantastic backhand. We can see a couple of the small technical flaws that make Federer’s backhand more susceptible to error than the other three. Although Almagro might make more mistakes off that wing at times, his are less likely to be mishits and are rather just missed targets resulting from a significantly more aggressive attitude off that side than Federer is wont to swow.