-

Movement – The Universal Athletic Position

Introduction

Athletic movement is a critical difference maker in tennis performance. It is also one of the areas that players struggle to improve the most. Movement patterns are learned and habituated at a young age. Most players develop their physical capabilities (strength, explosiveness) as the pathway to better movement. This neglects the technique component. Understanding the universal athletic component is a critical piece of movement technique.

Tennis requires a greater adaptability in movement than almost any other sport. A tennis player must be able to react explosively in all directions. While other sports also have this requirement, few demand this capacity in such a wide variety of circumstances.

For reactive movement in tennis, only the return of serve offers us an opportunity to reset. During a point we must constantly adapt our positioning, and the demands of the movement are changing.

As such, it becomes important to be guided by principles rather than rules. Understanding the essence of good movement gives us the ability to adapt our movement to the situation in front of us. What constitutes a perfect split step changes depending on where in the court we stand and our direction of travel.

Ultimately we are guided by three key needs:

1. Balance

2. Explosiveness

3. DirectionalityThe Universal Athletic Position

All movement begins somewhere. The position that we begin from influences the movement that follows. The better the starting position, the better the potential for the movement. Our starting position should allow us to be balanced, to generate power efficiently, and to move athletically in all directions.

Enter the Universal Athletic Position.

The Universal Athletic Position (UAP) is so named because it is the most common position in sports. While there are sports that don’t feature the UAP at all, most land-based sports feature some version of it in at least some aspects of the sport.

We don’t train and use the UAP because it’s in most sports though. It is in most sports because it is the most efficient stance to be able to react explosively in all directions. That’s what makes it universal. More specialized sports that feature limited dimensions of movement will tend not to feature the UAP. However sports that require reaction in multiple axis of movement (baseball, tennis, basketball, soccer, cricket, among others) all see usage of the UAP at the highest levels.

How does it address our three primary needs?

Balance

Balance and stability go hand in hand. The more stable a stance, the less athleticism required to remain balanced in it. An athlete standing on one leg on an uneven surface faces greater challenges than one with a wide stance on a flat surface.

Primary things to note here are stance width, posture, and weight distribution. Generally, the wider the stance, the more stable it becomes. Past a certain point that stability becomes counterproductive. An athlete in the splits will not fall over, but also cannot move very quickly. We should aim for a stance wide enough to provide stability (heels outside the hips) without compromising movement (narrow enough we can comfortably bend at the ankles, knees, and hips).

Good posture doesn’t always mean standing upright. It does mean good spinal alignment. Across sports we see great movers keeping their spine erect even as they have flexion in other joints.

Finally weight distribution. We should strive to have as much of our foot in contact with the ground as possible when our direction of travel is uncertain. Different movement directions require applying force to the ground through different parts of our feet. If an athlete is on their toes, they cannot utilize their heels for movement without first putting their heels down – costing valuable time.

Explosiveness

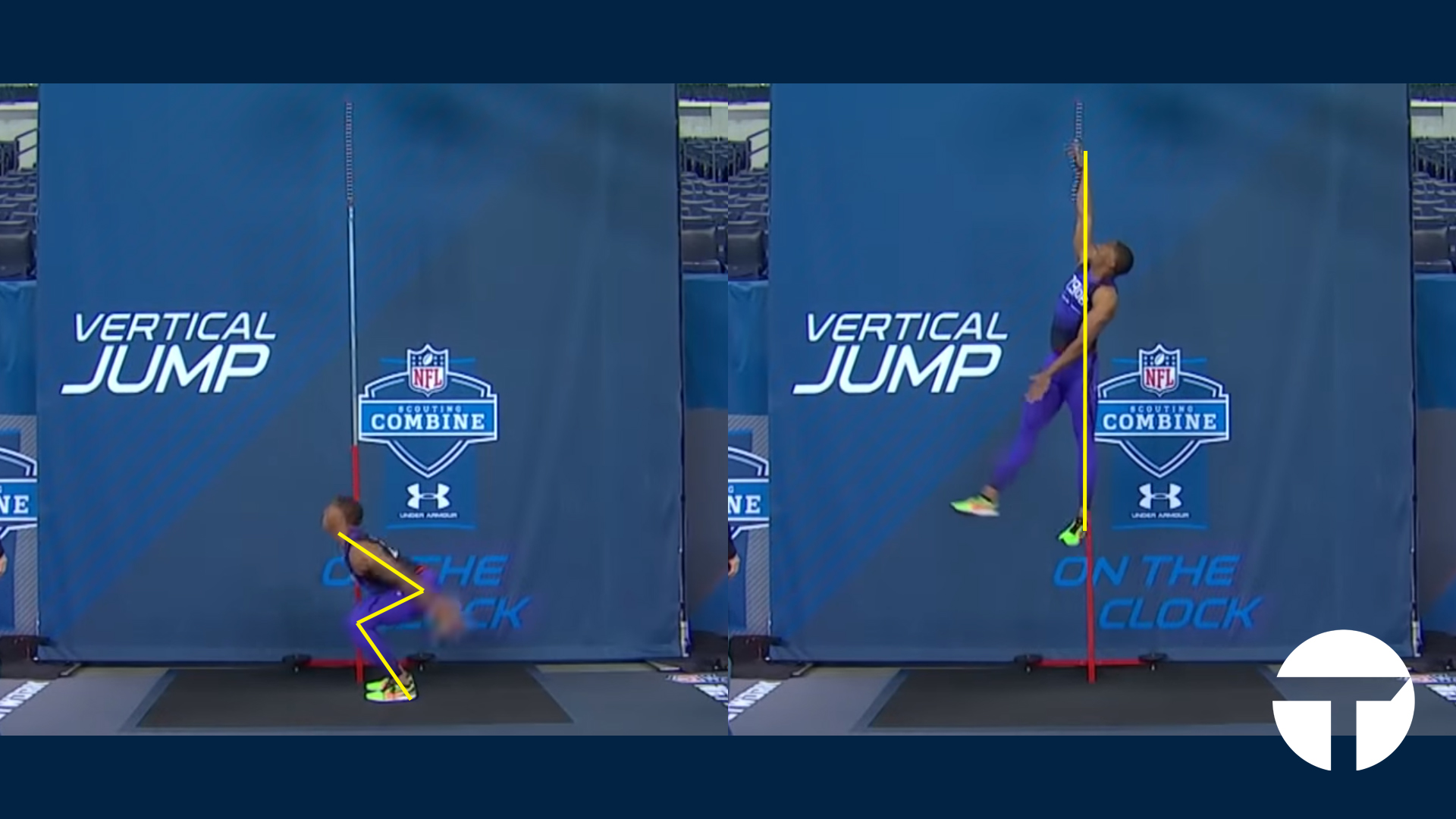

If we consider peak explosive movement from a stationary position, we can take cues from great jumpers. There is a significant overlap in the muscles used for a standing jump and those required for explosive movement laterally, forwards, or backwards.

Byron Jones set an NFL combine record for the standing jump. His goal (and that of any great jumper) is to recruit as many useful muscles as possible towards upwards propulsion. We can see he engages flexion at the ankles, knees and hips. This allows him to use all of the powerful muscles involved in extending those joints to launch himself upwards.

We want to follow a similar path. A good Universal Athletic Position will feature the same patterns of flexion, just to smaller degrees. We should have bends at the ankles, knees and hips to utilize our quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves to maximum effect. Where a tennis player differs from a great jumper is in the amount of flexion and the width of the stance. A tennis player must compromise their potential jump height to allow for the third criteria: directionality.

Directionality

All of that force we generate is useless if we cannot direct it in the appropriate direction. Thankfully, there is a large overlap between the demands for balance and those of directionality. As our stance narrows it doesn’t simply make balance more challenging – it limits our ability to apply force in any direction other than upwards. Widening our stance to outside of our hips lets us use a combination of extension, abduction, and adduction across our two legs to move forwards, laterally, or backwards.

Additionally we can manipulate our weight distribution to allow even more direction of our generated force. An elite athlete will initiate a controlled fall to align their body better with their direction of travel. In a wider stance, lifting our left foot and allowing a degree of falling to the left allows us to better drive force in that direction.

Putting It All Together

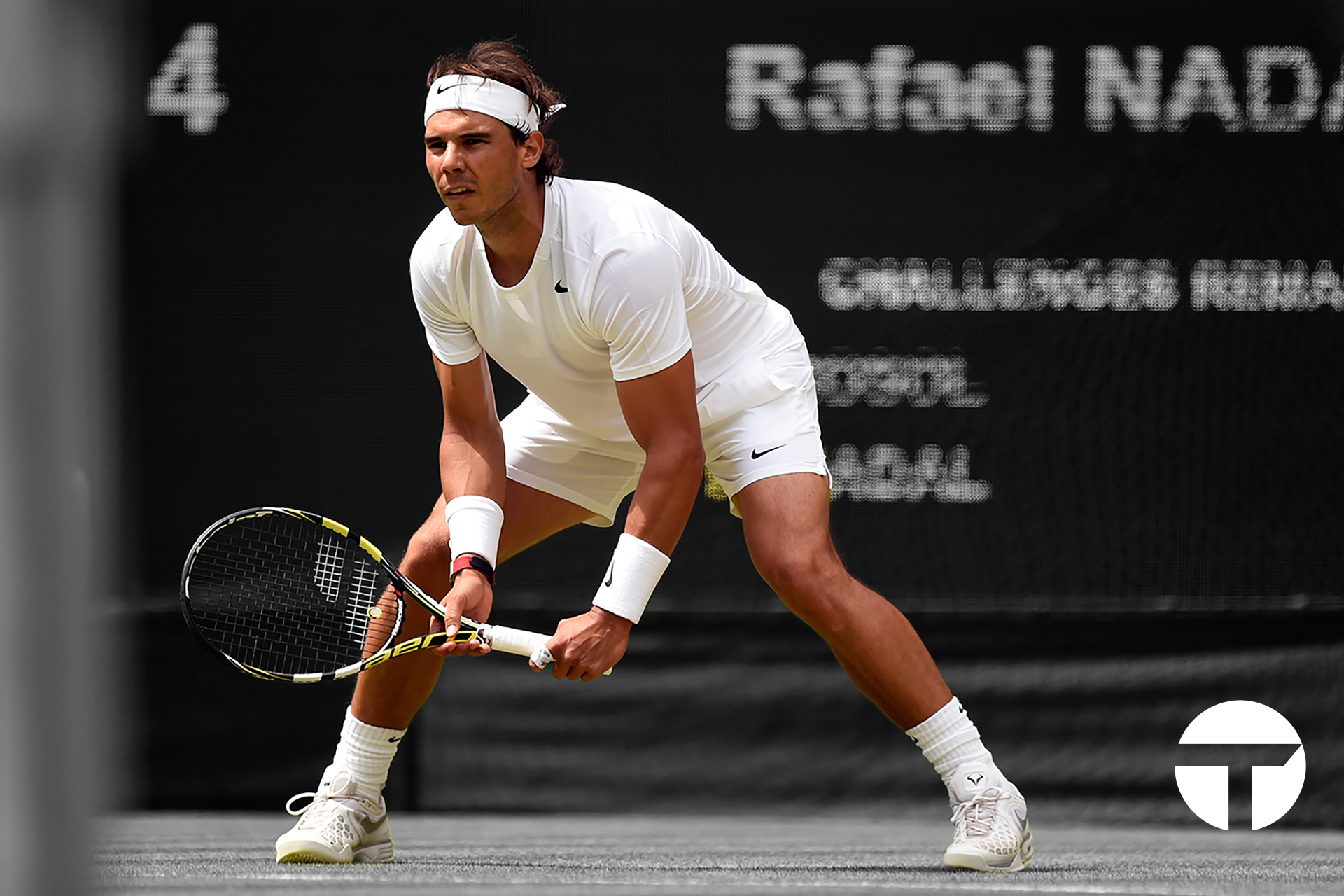

This brings us to the finished product. A tennis stance where our feet are wider than our hips without limiting hip and knee flexion. Where we engage flexion at the ankles, knees, and hips for maximum force production. Where we keep good posture, to allow better control of our balance.

In highly contested points, a player might only attain a complete Universal Athletic Position once (as the returner) or possibly not at all (as the server). However great tennis athletes are always moving towards a Universal Athletic Position. They will obtain (or retain) as much of it as possible even as they move dynamically around the court.

When we understand the principles behind a position rather, then we can strive towards those principles. This helps guide our movement in non-ideal situations. We can move away from a binary way of thinking about movement technique (either you reached the position or you didn’t) to something more sophisticated (I retained as much of an ideal position as possible).

This is a path to better movement, and better tennis.

For more content follow us on instagram, facebook, and tiktok!

-

2020 French Open Final: A Point With Rafael Nadal

2020 French Open Final: A Point With Rafael Nadal

Introduction

When Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic stepped onto Court Philippe Chatrier to contest the 2020 French Open Final, many predicted a resounding win for Novak. After all, Djokovic had come into the tournament with a 34-1 record for the year, his sole loss coming from a default due to a careless moment at the US Open.

Few would have imagined the match beginning with a 6-0 set for Nadal, nor the crushing victory he achieved over his main rival for the past decade. If it seemed Novak’s star was ascendent before the match, Nadal sent Djokovic crashing to the ground during it.

This was not by chance. Nadal hasn’t been lucky at Roland Garros 13 times. Rafa is the most dominant single-surface player in the history of the sport by a wide margin. Indeed we wrote briefly several years ago about some of the challenge Nadal presents on clay. In this article we will break down a point from this match, highlighting aspects of Nadal’s decision-making and positioning that led to his dominance on the day.

The Serve and Return

Much has been made of Nadal’s positioning on the return of serve. In recent years, he has retreated further and further behind the baseline to almost comical depth. At many tournaments, he cannot even be seen on the camera at times, and linespeople are forced to adjust their positions against the back walls to make room for him.

Nadal’s goals on the return of serve are simple: to make as many returns as possible, and hit returns that start the point in alignment with the way he wants to play the point. He brings a cohesive return strategy to the table in the same way Agassi did – just of a very different style. Agassi’s game was centered around hard, flatter groundstrokes, and his return game was a match to that. Nadal wants to hit high, heavy groundstrokes during the rally, and returns accordingly.

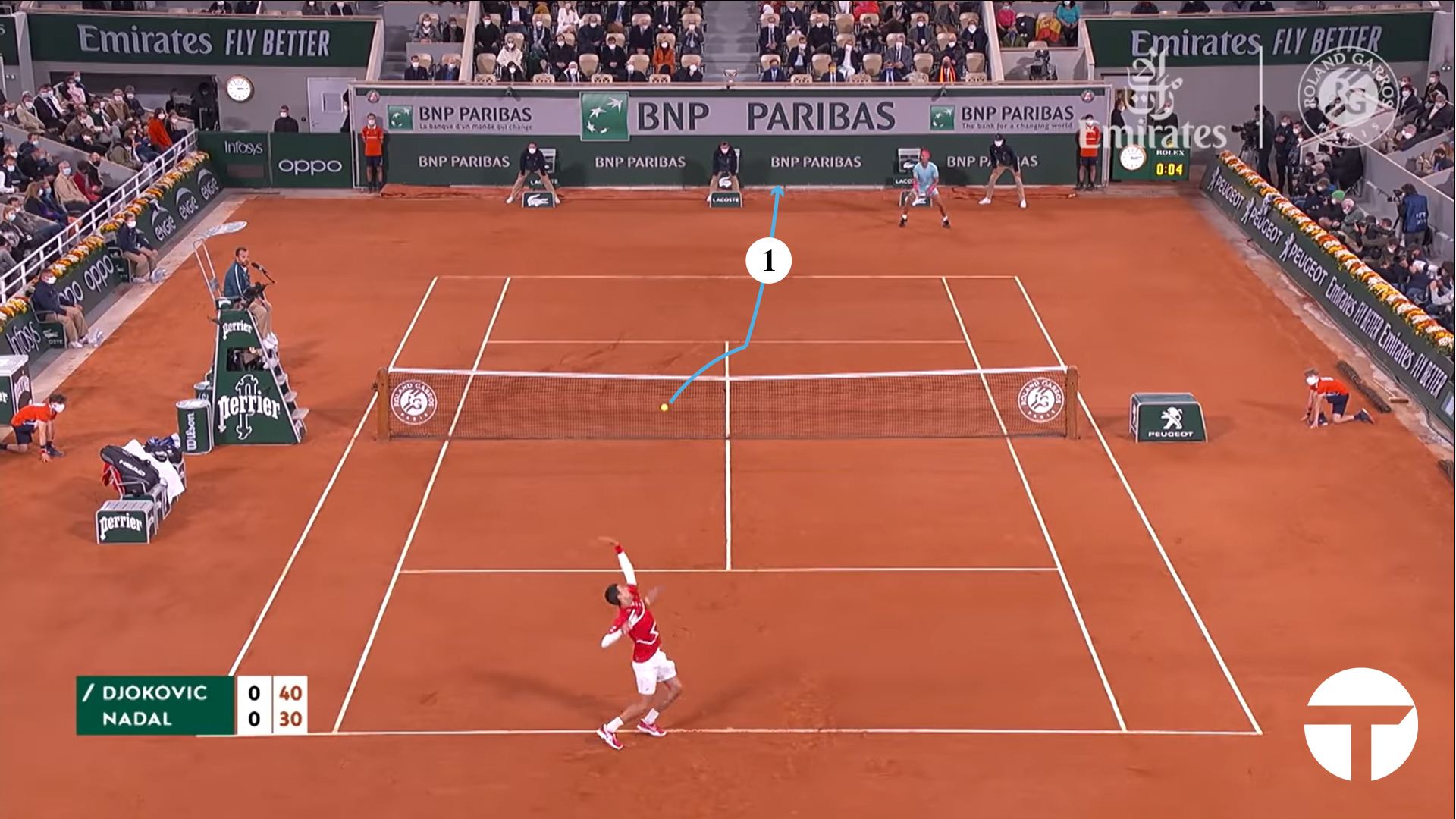

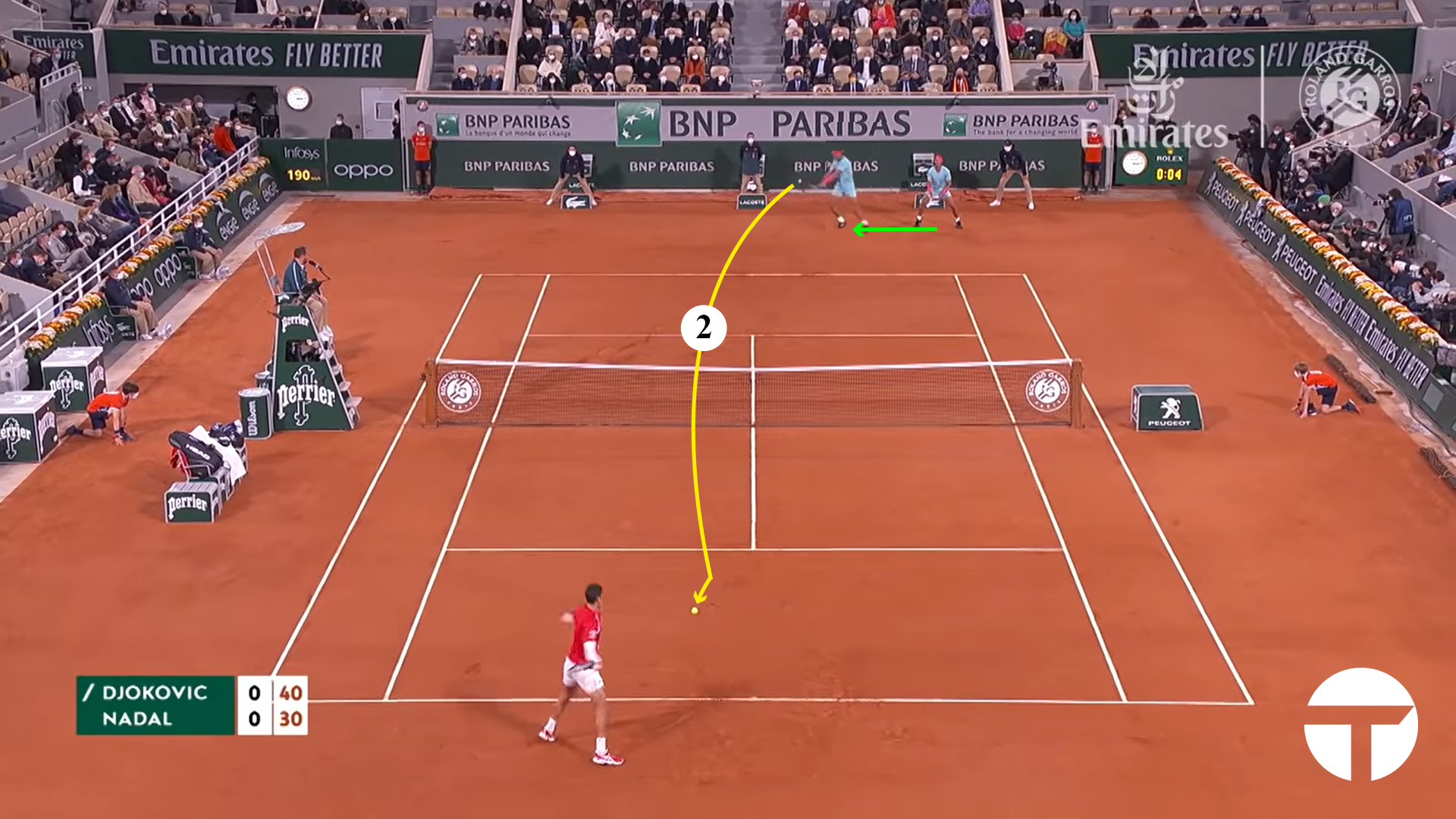

The point opens with a good quality serve up the T from Novak. While Novak’s first serve was generally pretty poor through most of this match, this particular serve was a strong one.

First note Nadal’s movement to the return. Positioned so deep, he is able to move laterally to the ball, keeping his balance neutral. This is a theme we will see throughout his clay court play. Nadal hits a high, looping backhand return with the goal of forcing Djokovic back and starting the point in neutral.

As we continue to move through the rest of this point, we will see that the players are faced with a series of choices that are not as simple as they might first appear. Here, Nadal has presented Djokovic with his first real choice during the point. Djokovic stepped up to the line knowing where he wanted to serve – everything after that is a reaction for both players.

The First Fork

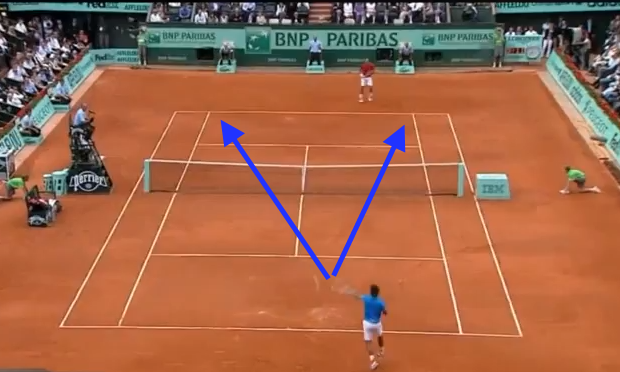

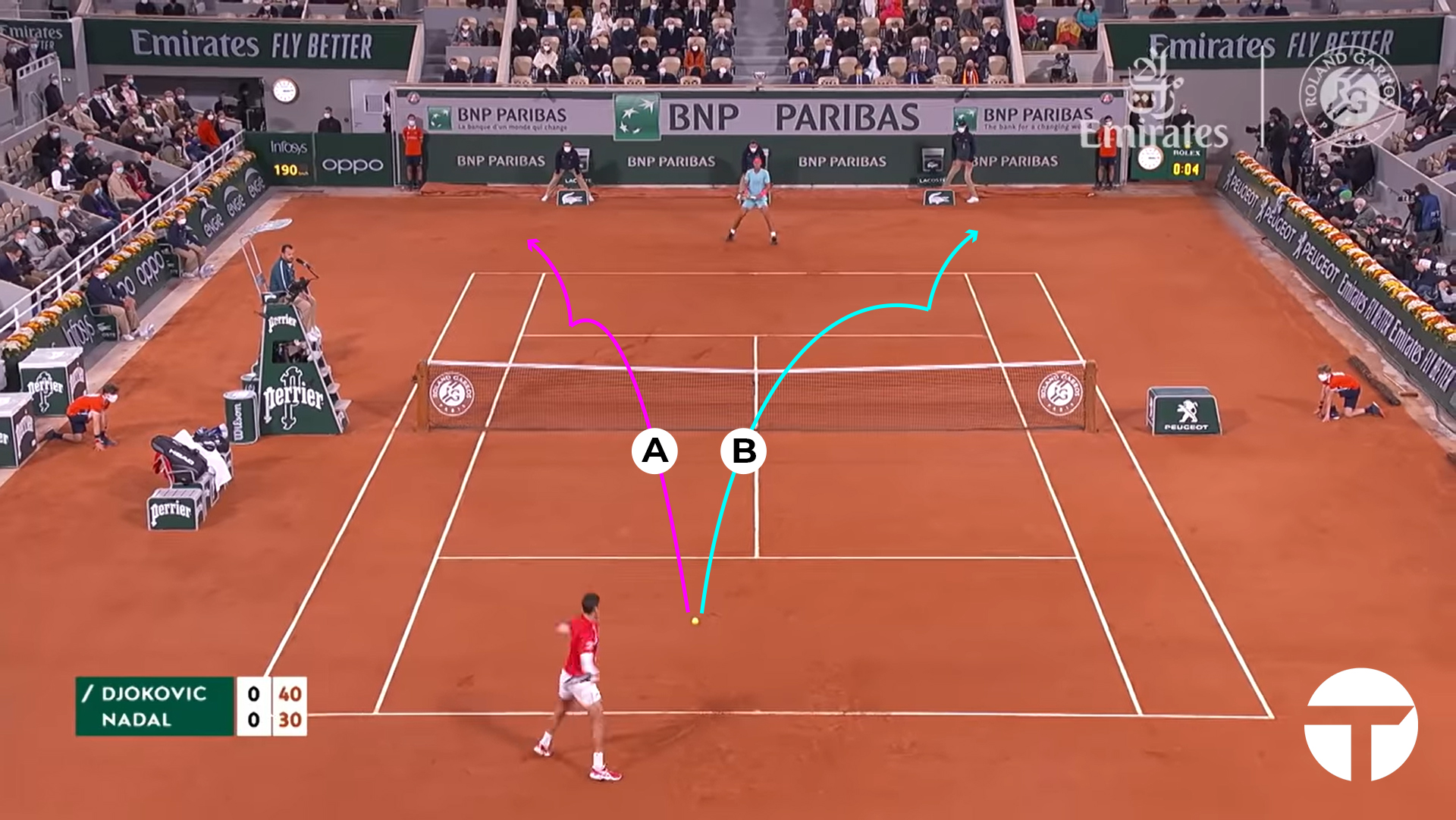

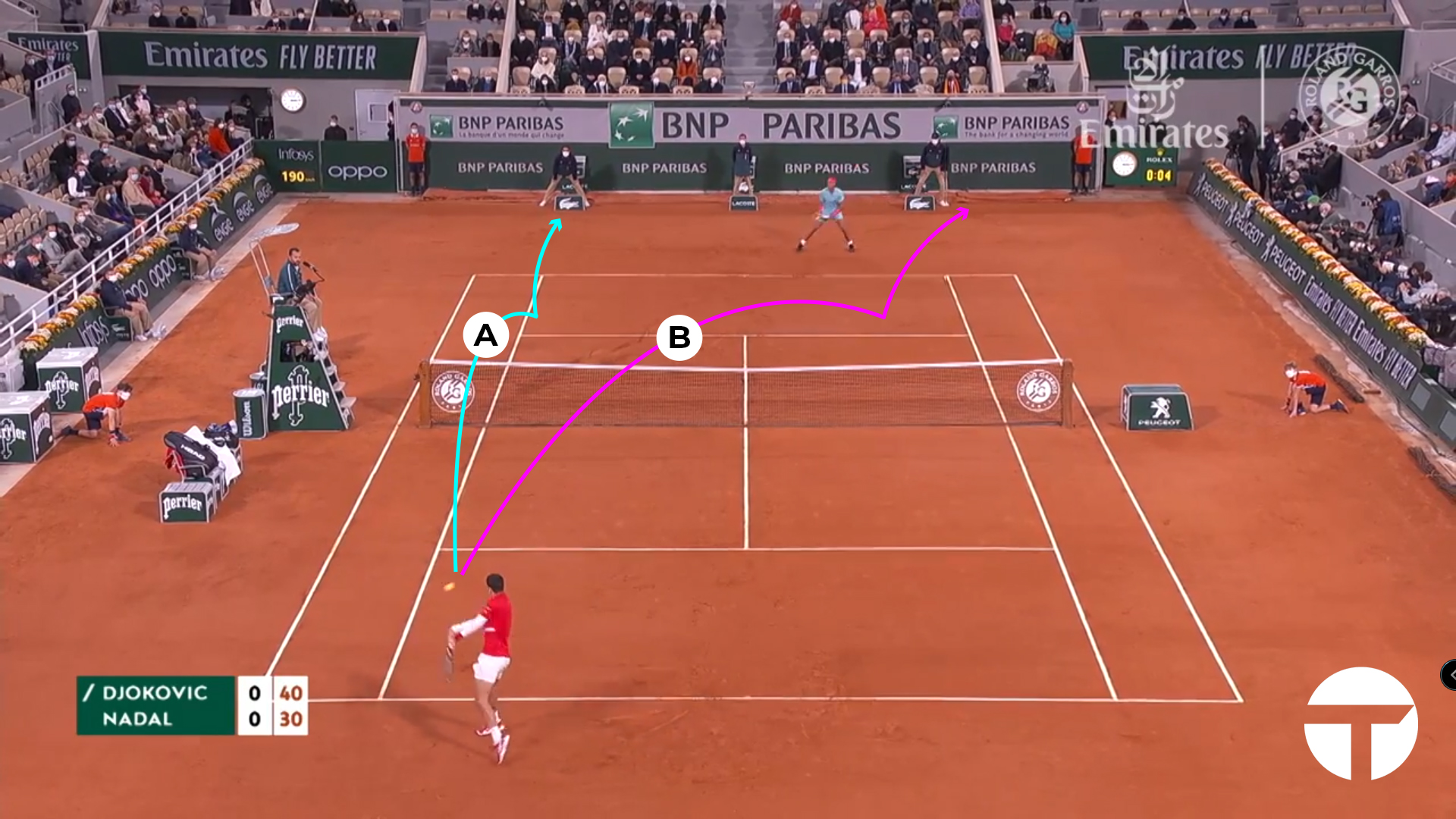

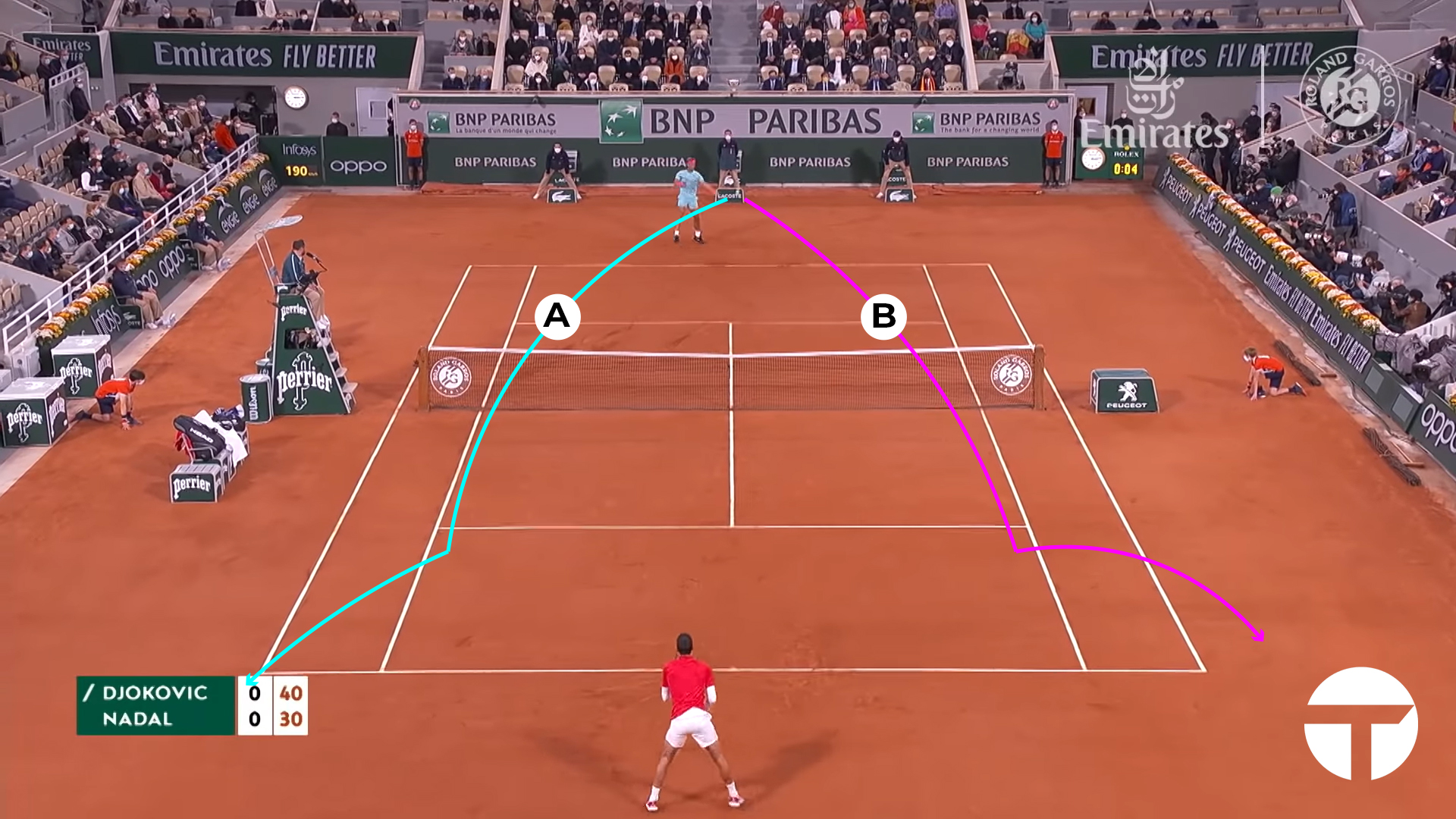

Nadal’s goal was to start the point as close to neutral as possible. Rafa didn’t quite achieve his goal in this case. Although he did push Novak back behind the baseline, Djokovic has control of the point from this first ball. Novak has two good options with his forehand – A & B. In chess, this would be a fork – being able to attack two pieces simultaneously. In high level tennis, these situations where a player has two viable attacking options usually lead to a victory in the point.

Rafa must respect both options, and positions himself accordingly. Approximately central in the court, he has retreated fairly deep behind the baseline to allow himself time to track the ball down on the clay.

Nadal isn’t the only one facing choices here. For Novak there is risk in both directions. Hitting to Nadal’s forehand runs the chance of immediate reprisal. However, being overly predictable and playing to Nadal’s backhand can give away the advantage.

Djokovic goes with option B. Opponents have had good success over the years attacking Nadal’s forehand. After all, Rafa has spent almost 2 decades hitting forehands from the deuce court at the professional level. That’s the position Nadal prefers to construct his points from when he can, so Djokovic seeks to catch him off balance by attacking the forehand corner.

It works, to a degree. He does succeed in catching Nadal slightly off-guard, but Nadal’s excellent positioning neutralizes this. Note how Rafa is able to move laterally to the ball without giving up any extra space. Nadal is not forced backwards by Novak’s attacking ball.Getting To Neutral

Nadal’s forehand here is almost entirely predictable. Although he is hitting slightly off the back foot, like any elite player Rafa is still able to generate significant power and spin. Nadal takes the ball cross-court, establishing himself in the rally in a truly neutral position for the first time.

Rafa could have taken this forehand down the line, but doing so would have put him immediately on the move again to cover the cross-court forehand from Djokovic. Let’s keep front of mind that Nadal wants to hit forehands, and constructs his points with this in mind.

Knowing that he has hit a high quality ball, Nadal recovers slightly forwards and towards the center. Had his shot been more defensive or lower quality, Rafa would have recovered backwards into a deeper position.

Cat And Mouse

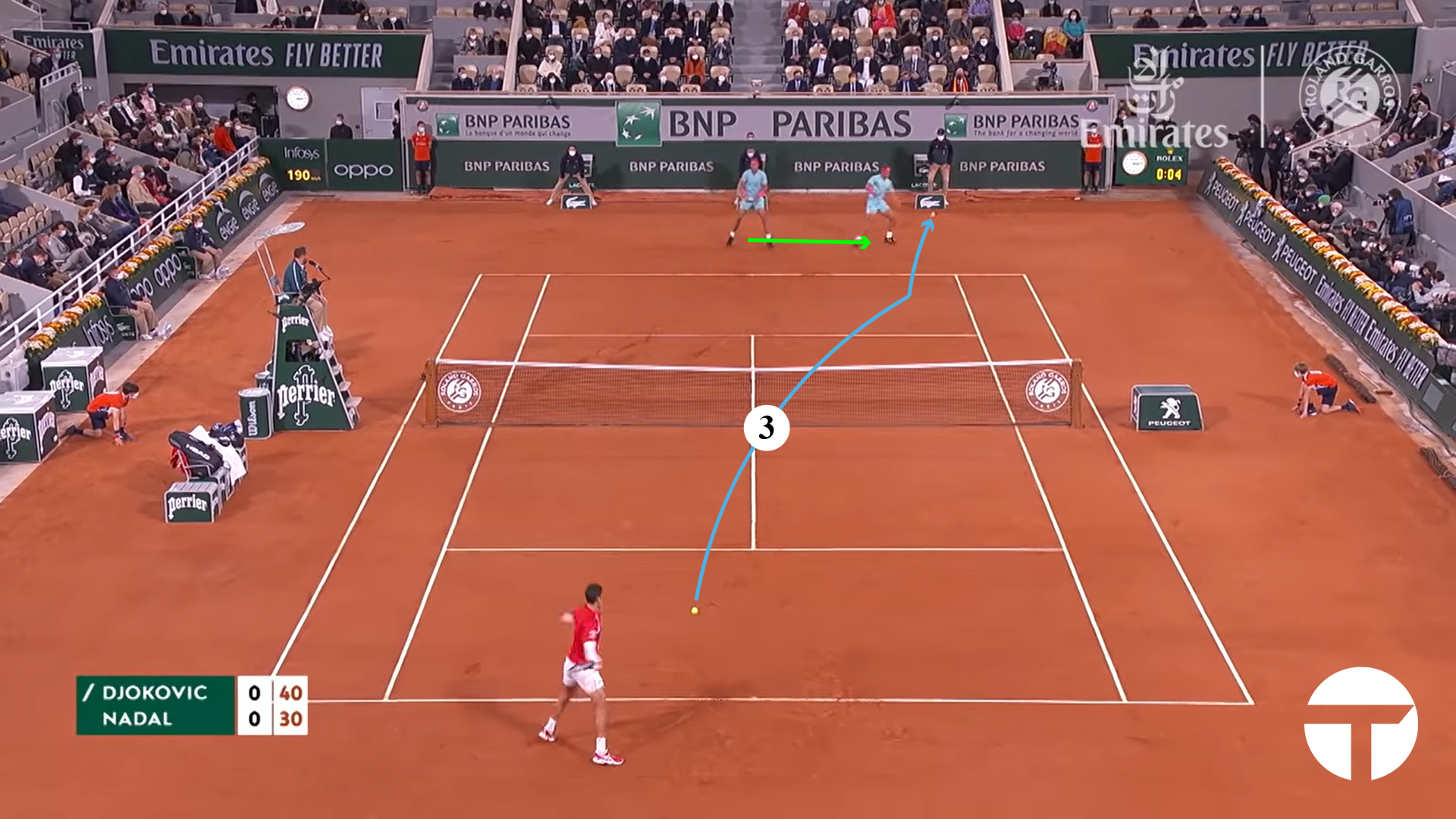

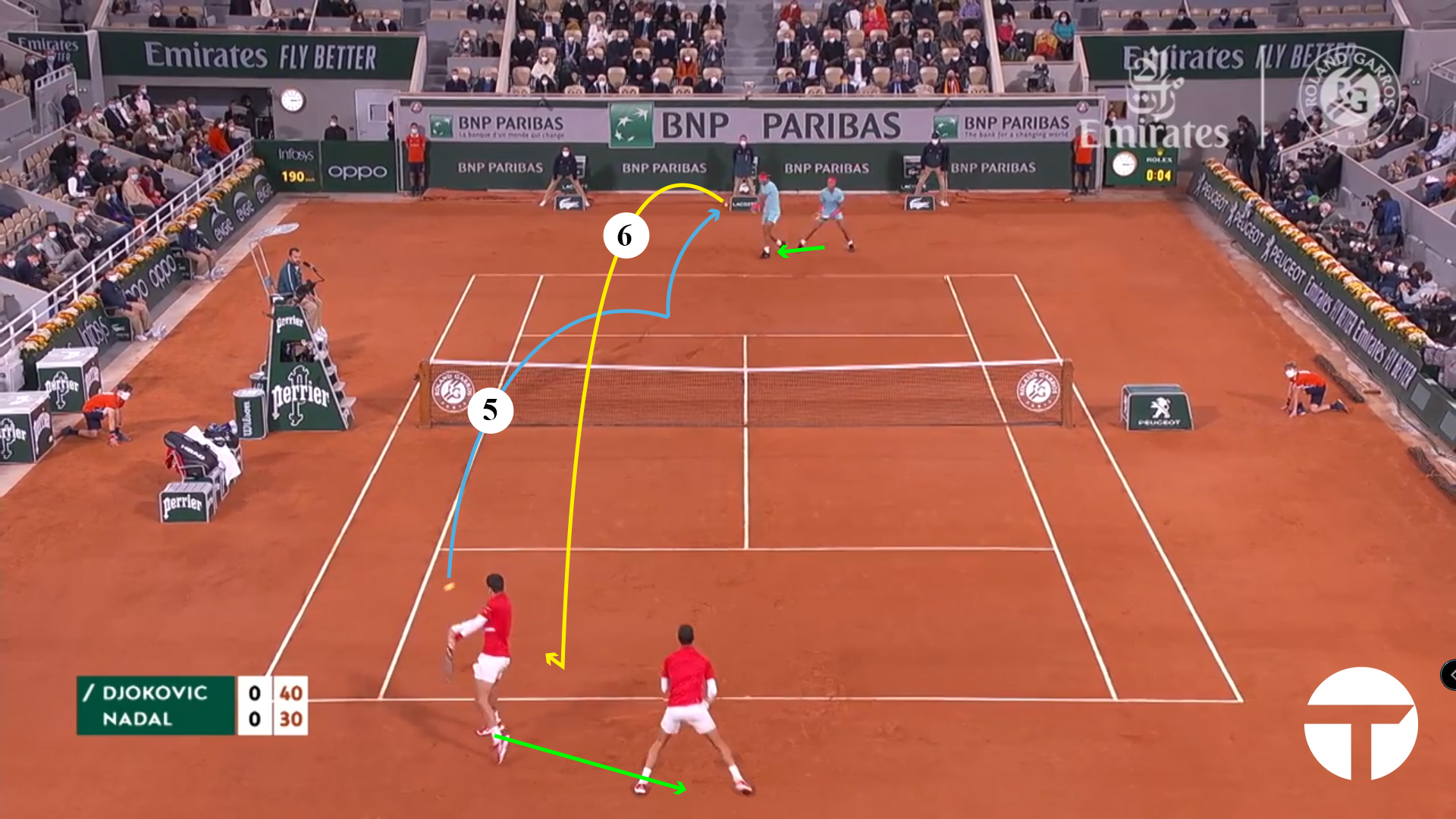

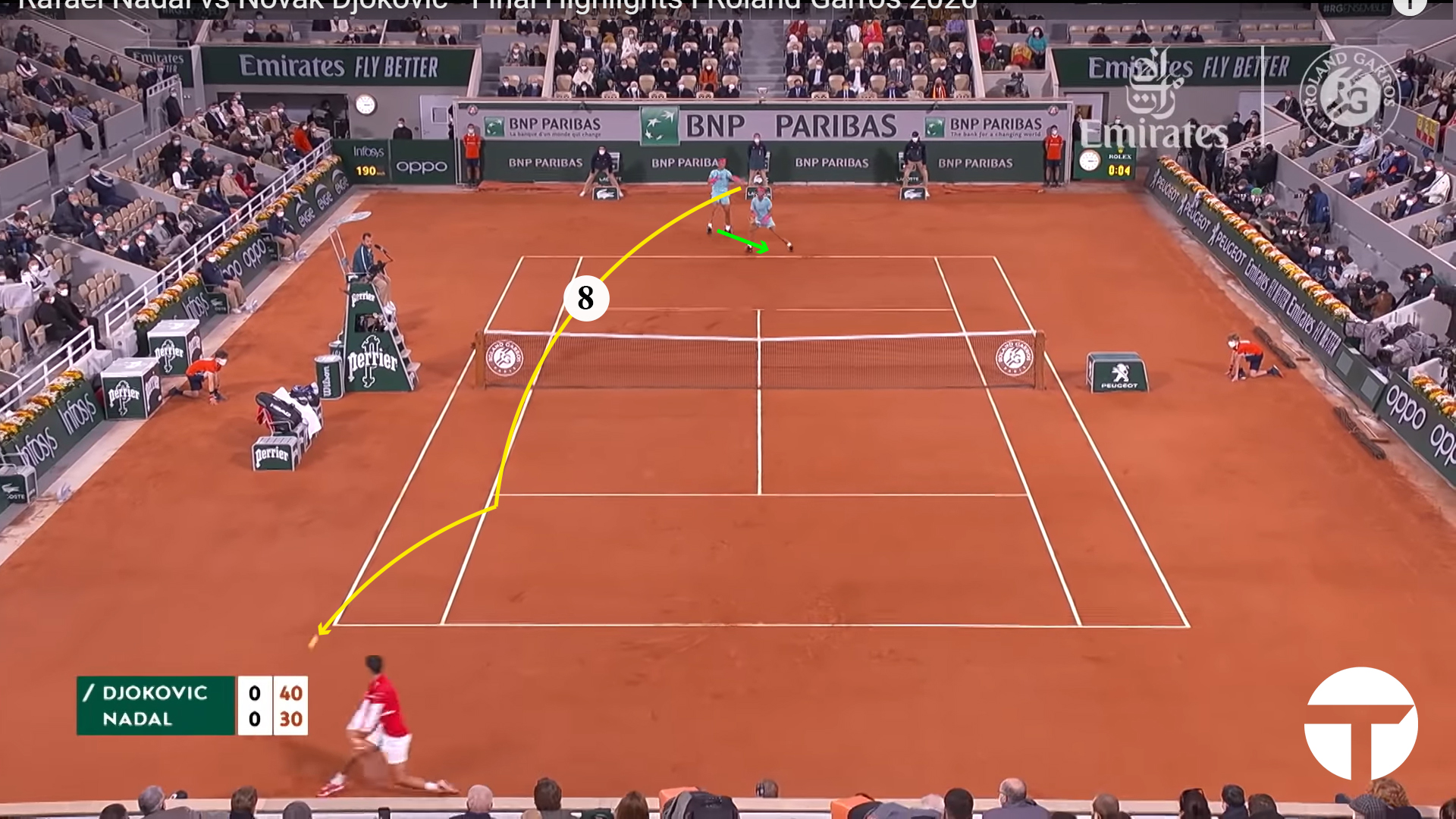

If we think back two shots, Novak had a middle of the court forehand that he could attack in either direction. Two shots later, Novak is hitting a backhand from behind the baseline in his own ad corner. Djokovic is faced with much the same choices he had two shots ago, but from a worse position. If Novak takes his backhand cross-court, he is trapping himself into a backhand-forehand rally where he is at a disadvantage.

However shot “A” is a high risk play. Novak’s margins down the line aren’t as good here, and he is not really in an attacking position. While Novak can take this backhand down the line, doing so is a genuine risk. Nadal is in good position to cover the shot, and for Novak to go down the line here without genuinely hurting Nadal would leave him open to the counter attack.

Now the cat and mouse game begins in earnest. Nadal’s forehand is the biggest weapon on the court. Both players know it, and much of their shot selection is driven by this knowledge. Novak wants to avoid giving Nadal forehands he can attack, but must still respect Nadal’s excellent backhand. Nadal meanwhile must try to maneuver the ball around to get himself a forehand, without putting himself out of position. Djokovic has the ability to hurt him off both wings, and Rafa must respect that.

Djokovic splits the difference. Not wanting to give Nadal the forehand, but also knowing he isn’t in position to be aggressive, Djokovic looks the backhand into the backhand-center of the court. This is a safe play, as Novak knows that Nadal doesn’t have time to run around the backhand. Rafa’s backhand as it its most dangerous from wider positions in the court – he cannot create as much angle from more central positions.

Because of his good recovery position after his previous shot, Nadal is able to take but two steps slightly forward for this next shot. Nadal knows he has a slight advantage now. When we look at Djokovic’s recovery position, we see that Djokovic knows it also.

We can often tell how players feel about their chances in the point by looking at their recovery positions. When a player feels good about their control of the point they recover forwards. When they have lost some advantage, they recover backwards. Djokovic moves back because he knows Nadal has the upper hand.

Nadal does something quite clever here. He has the advantage, but it is a positional one. Rafa is not in a truly attacking position – he is not yet in the end game of this point. So he plays the ball straight ahead, high and deep. Rafa knows that Djokovic had to recover to a very central position, he is able to force another backhand for Novak without having to push the sides of the court.

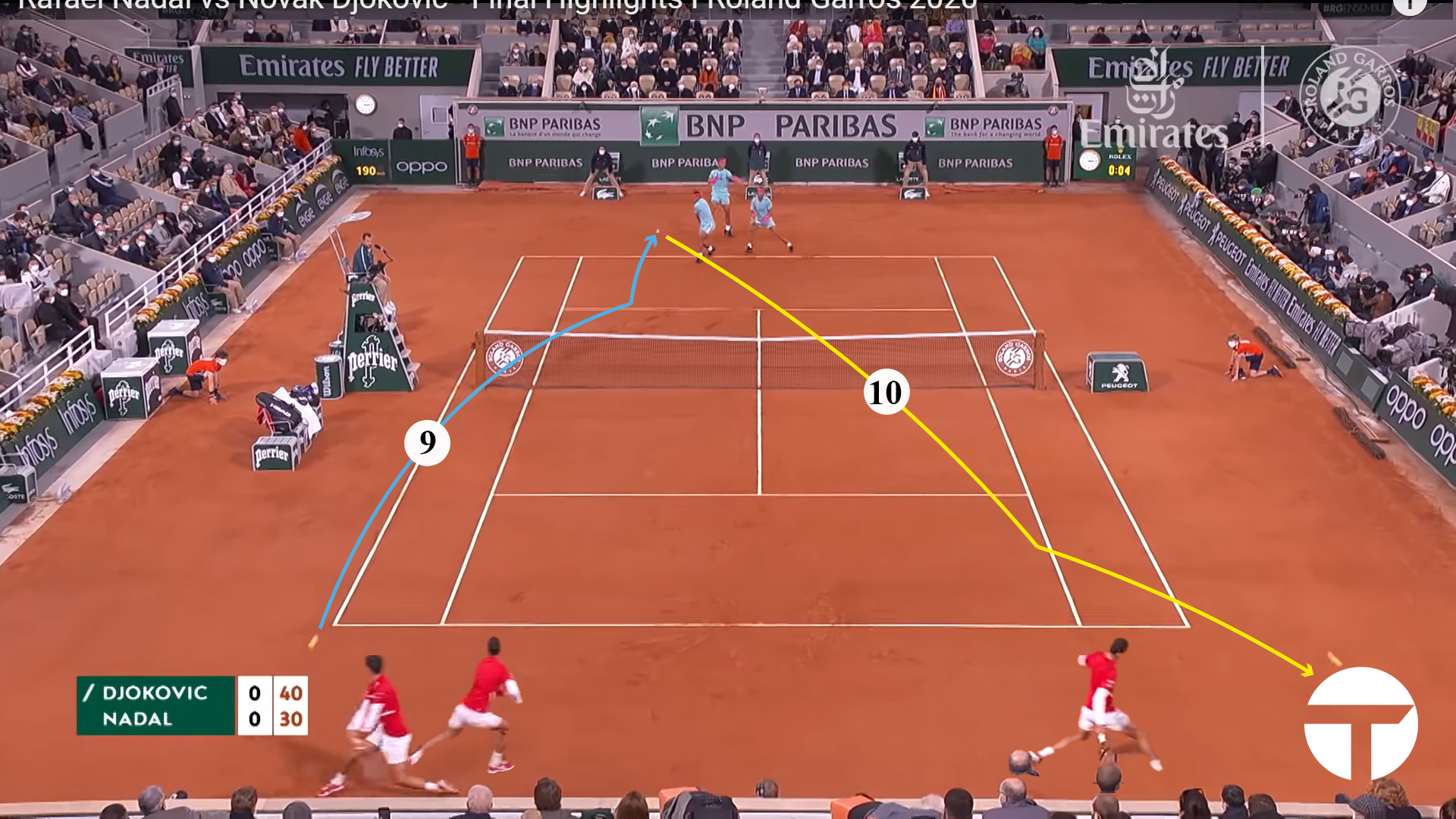

Falling Behind

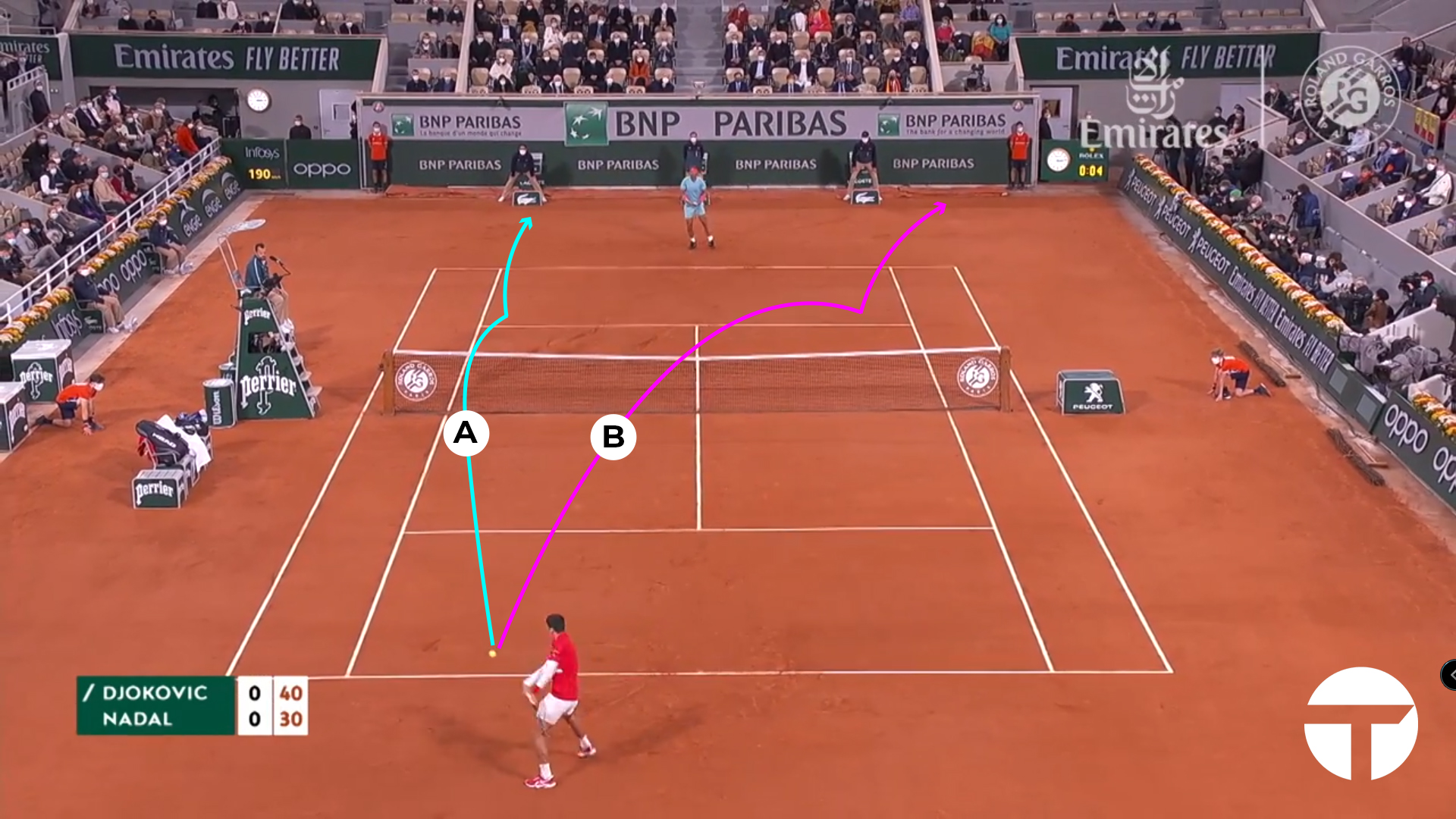

This position should look fairly familiar by now. Novak is facing the same choices he had earlier, but from an even worse position still. Djokovic is deeper behind the baseline, and has less angle to work with. Option “A” is even higher risk than it was earlier, but “B” still has the same dangers it had before. With each passing shot, Djokovic’s position in this point has weakened, and Nadal’s has strengthened.

It may not seem like it at a glance, but Nadal has Djokovic in real trouble here and Novak knows it. What would look like a reasonably neutral rally backhand to many is in actuality a highly dangerous position.

Djokovic abdicates the choice. In a bid for safety, he plays the ball almost straight head in a mirror of his previous backhand. Perhaps Djokovic thought he would sneak the ball to Nadal’s backhand again. Perhaps he thought this would be enough to stay close to neutral in the rally.

Whatever his intent, Novak puts the ball too close to the center of the court. A small shuffle to his right, and Nadal is hitting a forehand from a central position. It’s important to note that this is the second ball in a row that Rafa has barely had to move for in order to hit. Novak tried to avoid committing to anything, but you cannot delay making real choices against Nadal on clay. Part of the challenge is that Nadal is always asking questions to which there are no easy answers.

The Second Fork

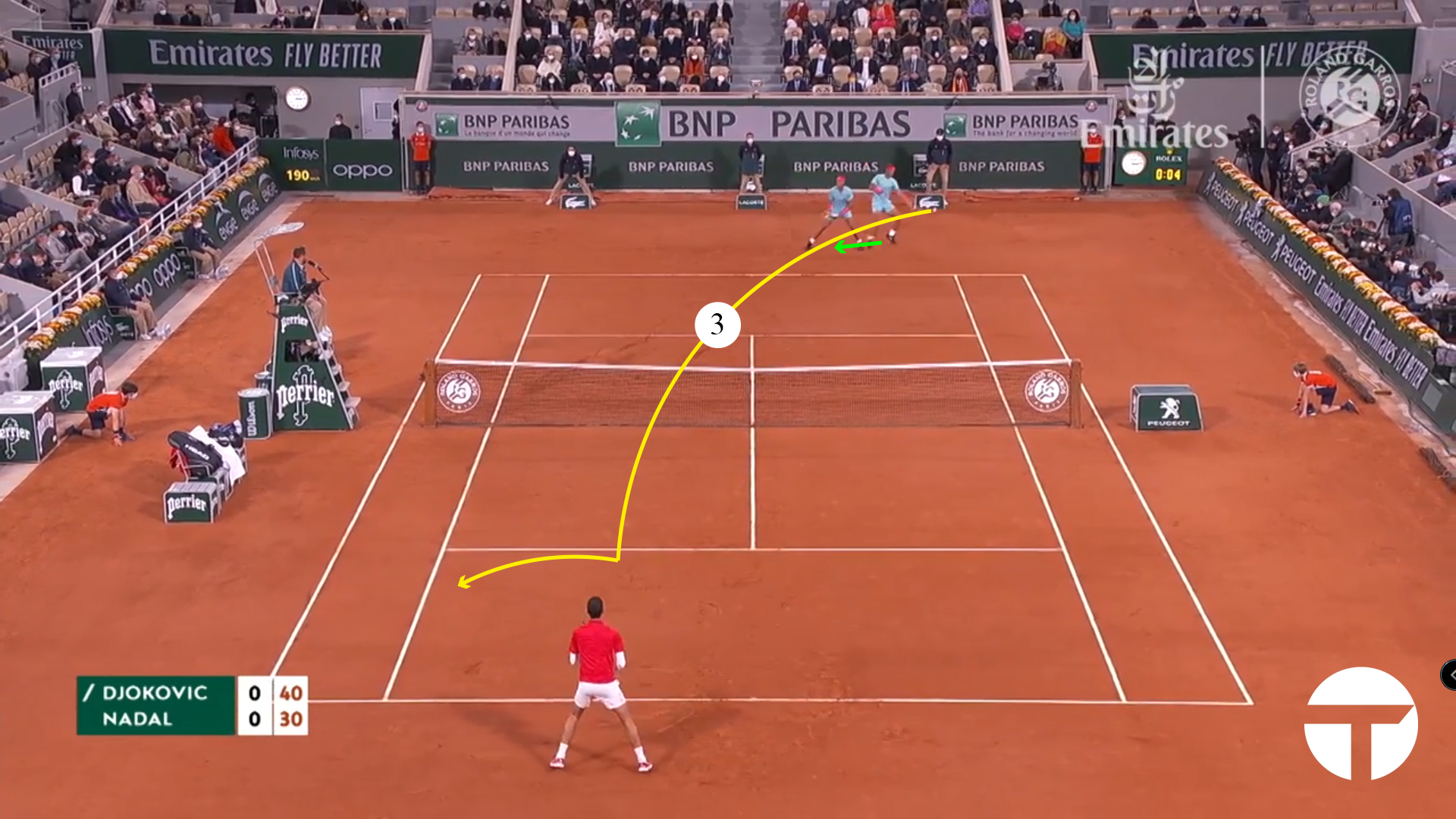

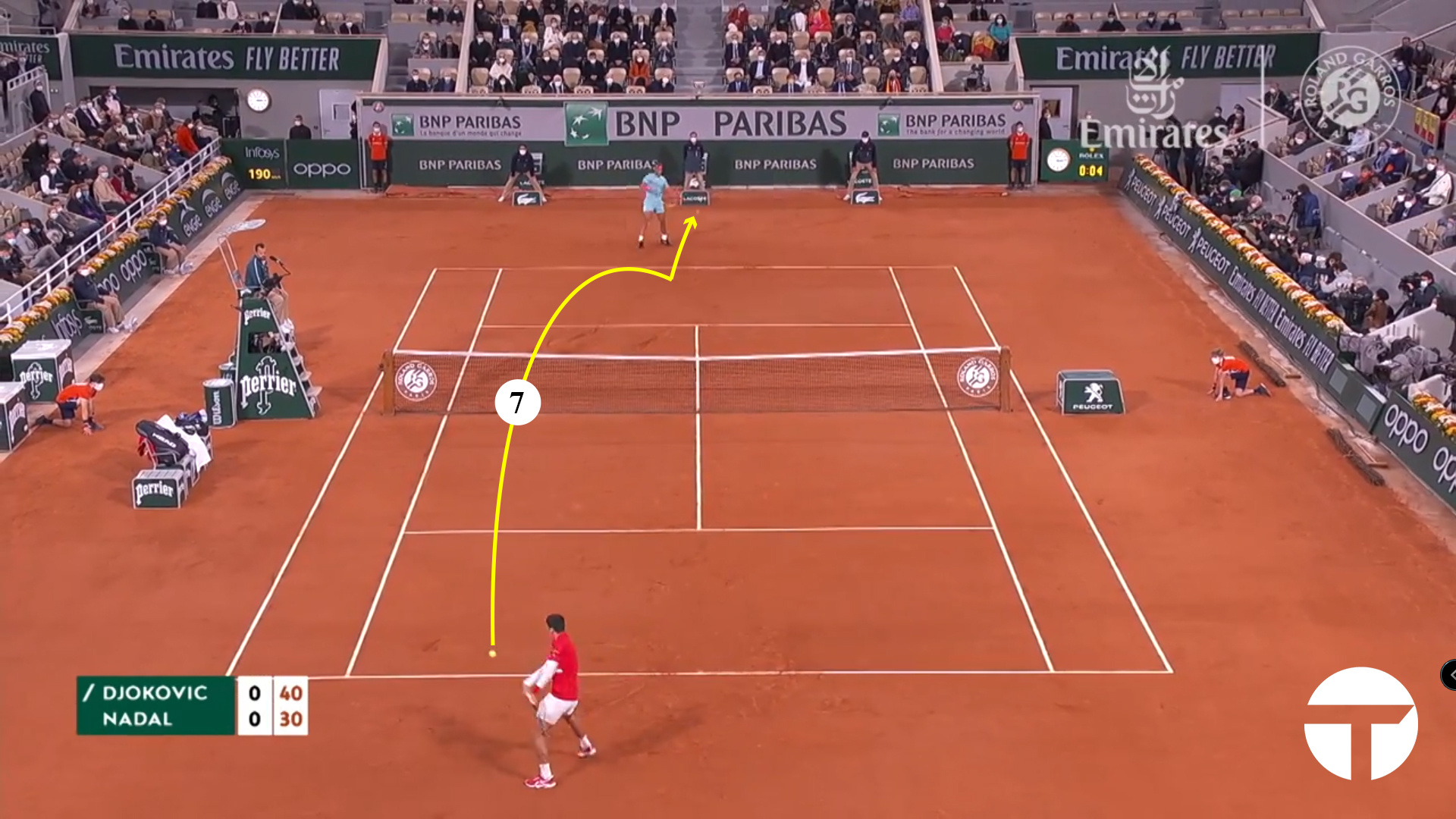

As it required minimal movement, Nadal is hitting a forehand while balanced and prepared. Rafa has two viable attacking options, and can hurt Novak with either one. Having the heavier forehand of the two, Nadal can hit with more angle than Novak. This gives him a wider spread of attack off this position.

Djokovic is frozen – stuck behind the baseline and having no ability to predict, he is trapped into pure reaction. On any surface this is a difficult predicament, but on clay perhaps more so. On the dirt, we pay a greater penalty for being off-balance than we do on any other surface. Novak is forced to take a very neutral position with a large amount of court to cover on his next ball.

Nadal attacks. Ripping his forehand cross-court, Nadal opens the court up. This forehand isn’t just heavy – it is angled. Note how close to the service line the ball bounces, forcing Novak to move more out of position laterally. If Nadal couldn’t have attacked either side equally, Djokovic would have been able to position higher up the court and cut this ball off. However as he was forced to react, Novak’s deeper court positioning puts him in a poor position here.

The other thing to watch is Nadal’s recovery position. Nadal has been able to move straight laterally or slightly forward to every single groundstroke in the rally so far. He has accomplished this by careful positioning – taking up the right place on the court between shots in depth as well as width.

The fact Nadal recovers forwards here is significant. Rafa is a shark who smells blood in the water. He steps up because he anticipates a more defensive reply from Novak, and for good reason. Djokovic is in real trouble at this point, with limited options.

Against most players, Novak’s backhand down the line combined with his foot speed would have been enough to keep him in this point. However Nadal’s clay court anticipation and positioning is too good. Expecting the shorter reply, Nadal recovered forward, then stepped in to take this backhand early.

If Nadal had stayed in a deeper position after his forehand hit he would have been far less likely to finish the point here. Being even one step deeper in the court might not have been enough to get the ball past a player as quick as Djokovic.Recovery Positions

Any high level player needs to be able to generate power and spin off the back foot. That said, there are advantages to not having to move diagonally backwards to shots. Hitting off the back foot requires more athleticism. Hitting from deeper in the court makes it more difficult to find angles, and gives more time to our opponents.

One of the things that makes Nadal so formidable on clay isn’t just his forehand, but his positioning. For every single shot in this rally, including the return of serve, Nadal was able to move either straight sidewards or forwards to his next shot. Even Djokovic’s one aggressive shot of the point didn’t push Nadal back in the court.

This is not because Nadal took everything on the rise, or refused to give up ground in the way that someone like Davydenko or Agassi might have. Rather, Nadal’s intuitive sense of the flow of the point allowed him to mostly predict what was going to happen next. On the one shot where he couldn’t predict (the forehand Djokovic hit right after his serve) Rafa positioned himself slightly deeper to compensate.

Conclusion

This is a busy point, for all that it was only 10 shots in total. We can see and learn many things from it when we take the time to break down the different positions and decisions each player faces and takes during the rally. Nadal and Djokovic are battling on several different fronts here.

The first is over Nadal’s forehand. Djokovic wants to avoid letting Nadal dictate play with his forehand. This means either keeping play to Nadal’s backhand, or only allowing Nadal to hit forehands that are more defensive in nature.

The second is over positioning. Even though Nadal’s forehand is the biggest weapon on the court, both players are perfectly capable of hitting a winner off either wing. This means the player with the better court positioning is likely to come out on top.

On hard courts, this second battle is easier for Djokovic to win against Nadal than it is on the clay. Novak can take Nadal’s forehand on the rise on hard courts at least some of the time. The sometimes unpredictable clay court bounce combined with Rafa’s heavy, and often off-center rotation, make taking the ball on the rise significantly more difficult.

While no two points were identical in this match, these two things were underlying the decisions each was making throughout the match. We can see these kinds of complexities in every matchup. The battles are not always obvious, and the clues as to who is winning them can be subtle. Recovery positions, movement to the ball, and forks are all good indicators of how things are progressing.

-

Tactical Tennis Podcast #1 – Raonic, Nadal & Kyrgios

The first podcast episode for Tactical Tennis with Glen Hill and Jacob Meyer explores three main topics: Roanic, Nadal and Kyrgios. Of course that’s only the beginning – Carlos Moya, Malivai Washington and Andre Agassi’s bowlegs also get a mention, among many other things.

Tactical Tennis Podcast will explore the world of tennis with a critical eye for tactics, technique, training and psychology (all through the lens of science where ever possible!). Topics will vary wildly from week to week, with each episode touching on three main ideas, themes or players.

/RSS Feed

/RSS Feed -

Facing The Bull: Rafael Nadal

In the wake of Nadal’s first-round struggles against German Daniel Brands, the press has raised questions as the press is wont to do. Most of these questions have centered around the dip in form Nadal must have suffered to drop set to a career journeyman such as Brands – indeed Nadal lost as many games in four sets on Monday as he did in the first four rounds last year. Such questions are not merely short-sighted, they show a genuine lack of understanding of just who Nadal is as a tennis player. He has suffered some huge upset losses in his career – Rosol at Wimbledon, Soderling at the French to name just two – and has had some near escapes too. In 2011 John Isner led Nadal two sets to one at Roland Garros before falling to the Spaniard’s will as just one example. But the magnitude of those losses highlights just how good Nadal is – those standing on the peak of the mountain have the furthest to fall. His performances over most of the last decade have been sterling. What can we learn from Nadal’s losses and close misses? How does one take on the Bull on the clay and live to tell about it?

The Magnitude Of The Task At Hand

Nadal’s dominance on clay has officially reached unheard-of heights. He has lost a mere 11 clay court matches in the last 9 years stretching all the way back to 2005. In fact he is more difficult to beat on clay than any player has been on any surface in the Open Era (or perhaps ever). His career win rate on clay of 93% exceeds even Federer’s on grass which is a ‘paltry’ 87.3% in comparison. It is important to highlight this so we understand just what a difficult proposition it is to defeat Nadal on clay. In fact only three men have ever beaten Nadal twice on clay in his entire career – Djokovic, Federer, and former French Open champion Gaston Gaudio. Both of Novak’s victories over the Spaniard came during his amazing run in 2011, and Gaudio’s wins over Nadal happened when Nadal was 16 and 17 years of age.

The Scouting Report From The Bleachers

The skinny on Nadal is that he struggles most against tall, big serving players with big forehands and two-handed backhands. And on paper that makes perfect sense. The two-handed backhand helps to negate the power of Nadal’s high-kicking cross-court forehand. The big serve allows them to put Nadal on the defensive early and use their big forehand to dictate play to his backhand. And lastly the height makes it harder for Nadal to kick the ball up out of their strike zones with his forehand. Many of his biggest losses have come against players who fit some or most of the mold. Robin Soderling, Lukas Rosol, del Potro and the like. However most players these days sport two-handed backhands, and tall guys with big serves and big forehands give everyone trouble when they play well.

So if we accept that Nadal struggling against big serving players with big forehands as nothing to get excited about, are there other matches – either losses or close calls that we can learn from? Is there something deeper?

Digging Deeper

So let’s take a look at Nadal’s career head-to-head versus various players. We of course remove Murray, Federer and Djokovic from the mix – while matchups certainly play a part the level of play all of these players are so complete it is somewhat harder to discern patterns. We also take away the ‘big men’ with big serves and forehands, and lastly remove players like Gaudio whose entire experience against Nadal came when Nadal was 16 or 17. After this, three names leap out at us. Mikael Youhzny, James Blake and Nikolay Davydenko.

Youzhny’s career head to head with Nadal is 4-10. In and of itself nothing to get excited about, but given Nadal’s head to head against most players of Youhzny’s caliber it is a very respectable record. How has he accomplished this? Youzhny has excellent court sense and likes to take the ball on the rise. He also hits a relatively flat, penetrating ball of both wings. Blake not only swung pretty much as hard as he could off both sides, he did so from a fairly advanced court position. This allowed him three wins in seven meetings with the Spaniard. Then there is Davydenko. At 5’10 and 150 lbs soaking wet, one wouldn’t expect him to stand up well to the muscular bull from Spain. However Davydenko doesn’t just hold a winning head to head against Nadal (6-5), he has won four of their last five meetings. Nikolay takes the ball as consistently early as any player in the history of the tour. In fact he is more reluctant to back down and give up ground than anyone I’ve ever seen (including Agassi).

So let’s tie these three in with our earlier information and we come to…

A Question Of Time

“If you give Nadal time, there’s no chance. You have to be aggressive. That’s my view.” – Lukas Rosol, 2012

When we group players that take the ball early on the rise with tall guys with big serves and big forehands, what do they have in common? Time. Whether by position or pace, both types of players steal time from Nadal. And certainly we might say that making your opponent feel rushed is a good thing, and that many players, when rushed, will drop their quality of play. On the other hand, giving some players more time is like giving them rope with which to hang themselves. Some players like a fast pace, others like a slower tempo. Nadal definitely falls into the latter category.

Playing Nadal, especially on clay, is a war of attrition. With his heavy spin and intelligent use of the court Nadal wears his opponents down (although given his intensity on the court perhaps it would be fairer to say he bludgeons them into submission). He is like a boxer who goes to the body, pounding the lungs from his opponent. The only way to combat that is to keep the points short, or if a point is going to be long, be sure that Nadal is the one doing the running. Nadal’s opponents must play first strike tennis to have a true chance against him on the clay. The moment they release control of the point to him the punishment begins.

However attacking from the very beginning changes the tone of the match. Nadal is all too happy to retreat at times, and can end up playing far more defensively than is good for him with a little encouragement. Once he starts playing from deeper and deeper positions behind the baseline, his heavily spun forehand has a tendency to drop shorter in the court, making it even easier for his opponent to control the space. Nadal is an intelligent player, and often makes the necessary adjustments relatively quickly but getting off to that positive, attacking start is critical to have a chance against him.

It is not much of a weakness, all things considered, but then with great players it never is. Federer’s one-handed backhand is genuinely one of the greatest in the history of the game and yet it is still the chink in his armor. So it is with Nadal – rushing Nadal is no guarantee of success, but it is certainly the best shot you’re likely to get.

Attack The Strength

In addition to stealing time from Nadal, you must also attack his forehand. Nadal is at his most dangerous when hitting a forehand from the center of the court laterally. Whether he is behind the baseline, in front of the baseline or on it, the central court position forces opponents to respect his ability to angle balls off in both directions. On clay especially this creates a moment of hesitation as he hits the ball, freezing them in place and costing them a valuable step in getting to the ball.

We prevent this by not being afraid to venture into the lion’s den. It is similar to how one opens up the backhand against Federer – go hard into his forehand corner first, then to the backhand on the next ball. With Nadal however it can be fruitful to go at his forehand for two, three or four consecutive shots. He is more likely to drop balls short off his forehand than his backhand, and with each successive shot Nadal must respect more and more the possibility that the next ball could go into his backhand with aggression. Just as he freezes his opponents with the center-court forehand this in turn freezes him. As an example watch the first point of the video link below:

Believe

“I felt if I can win one set, why not the second one, and then the third one?” – Robin Soderling, 2009

The last step in having a chance to defeat Nadal on clay is belief. By all accounts Nadal as a person seems worthy of respect. However you can respect him as a man and player without allowing that respect to turn into fear. Against most players on clay, Nadal has won before he has even taken the court. His reputation weighs on his opponents, smothers them to the point of despair. Nadal is known for a very aggressive pre-match warmup. He wants to intimidate his opponents before a point is played and hitting the ball hard and with lots of spin during the warmup is one way to do that. Nadal’s amazing record on clay does the rest.

Who among the players on the men’s side truly believes they can beat Nadal at Roland Garros? Djokovic, for a certainty. Youzhny is quirky enough to think he has a shot, and Isner’s past near-upset just might give him the belief. Of course Youzhny and Isner would have to get through Djokovic first. In Nadal’s quarter of the draw there is Davydenko, but for all Davydenko’s winning record against Nadal he has never beaten him on clay and probably wouldn’t expect to here. Jerzy Janowicz has a real shot, if he can get through the hurdles of Wawrinka and Gasquet, and then Gasquet himself could take a crack with that beautiful backhand of his.

All things considered, Nadal received a genuinely tough draw for this tournament. In some years past he’s reached the final without once facing a credible threat but this year he has several. For all that he looks strong and healthy, and far more likely to make the finals of Roland Garros in 2013 than not. A week from Sunday the most probably outcome is Nadal to take the court in the final against his best frenemy, Roger Federer.

-

Where Have All The Prodigies Gone?

In 1985, one year after turning professional, Boris Becker won Wimbledon at age 17. Four years later, Michael Chang would win the French Open at the same age (albeit a few days younger). Mats Wilander netted his maiden grand slam title also at 17, whereas Bjorn Borg didn’t get his until 18 years of age. Edberg was 19. The list of youthful grand slam winners is long. Moreover these same players were not just grand slam winners, but long-standing players who reached the pinnacle of the game at a young age and stayed there for a long time. It is startling therefore to realize that at the time of writing there is not a single player under the age of 20 in the top 100 men’s singles players in the world. Ironically we have Stepanek at age 34, Llodra will turn 33 this year, and Federer sits at #2 in the rankings closing in on his 32nd birthday. The days of teenagers in the top 10 has gone – conversation of the ‘next generation’ of players in the wake of the big 4 centers around a group of 20-24 year olds – only one of whom is currently ranked in the top 20. All of this begs the question: where have all the prodigies gone?

(more…)