-

Serving Mechanics – The Jump

Introduction

4% doesn’t seem like a lot. In tennis however it can make a world of difference. 4% can be the difference between retiring a millionaire and barely making a living on the pro tour. It is the difference between being Roger Federer (54.14% of points won, 20 Grand Slams) and Andrei Pavel (50.14% of points won, 0 Slams). 4% is also the difference in Federer’s first serve % (62.1) and Stan Wawrinka’s (57.9%). Roger is 8th on the ATP’s all-time servers, while Stan sits at 61st.

Federer and Wawrinka provide an interesting contrast. They are two men who are of about the same height, who serve at virtually identical average speeds, with similar aces per match. Yet one of them is considered among the best servers of all time, while the other is not. One is a very good server, while the other is great. What is the difference?

We will use the two (and others) to contrast several aspects of the serve over the next few articles, beginning with the jump. Before we dive in further, it is highly recommended that you read the previous two serve mechanics articles on the ball toss (Part 1, and Part 2). All aspects of the serve impact each other, and understanding ball toss is a critical piece of setting yourself up for success when it comes to the mechanics of the jump in the serve.

Why We Jump

We do not jump in the serve for power (or any other stroke). This is important, because it is a fundamentally misunderstood part of biomechanics at all levels of tennis. We do not jump for power.

When we jump, we are at our maximum velocity in the instant we leave the ground. By the time we hit the ball at the peak of our jump, we are at our lowest possible velocity. Indeed, at the peak our upwards velocity is precisely zero.

The energy from the jump does not go into the ball. We exchange the kinetic energy of our jump for the potential energy of being up in the air. Once we hit the peak of our jump, gravity helps us convert that energy back into kinetic energy (by falling).

We do not jump for power, we jump for height.

Height At Contact

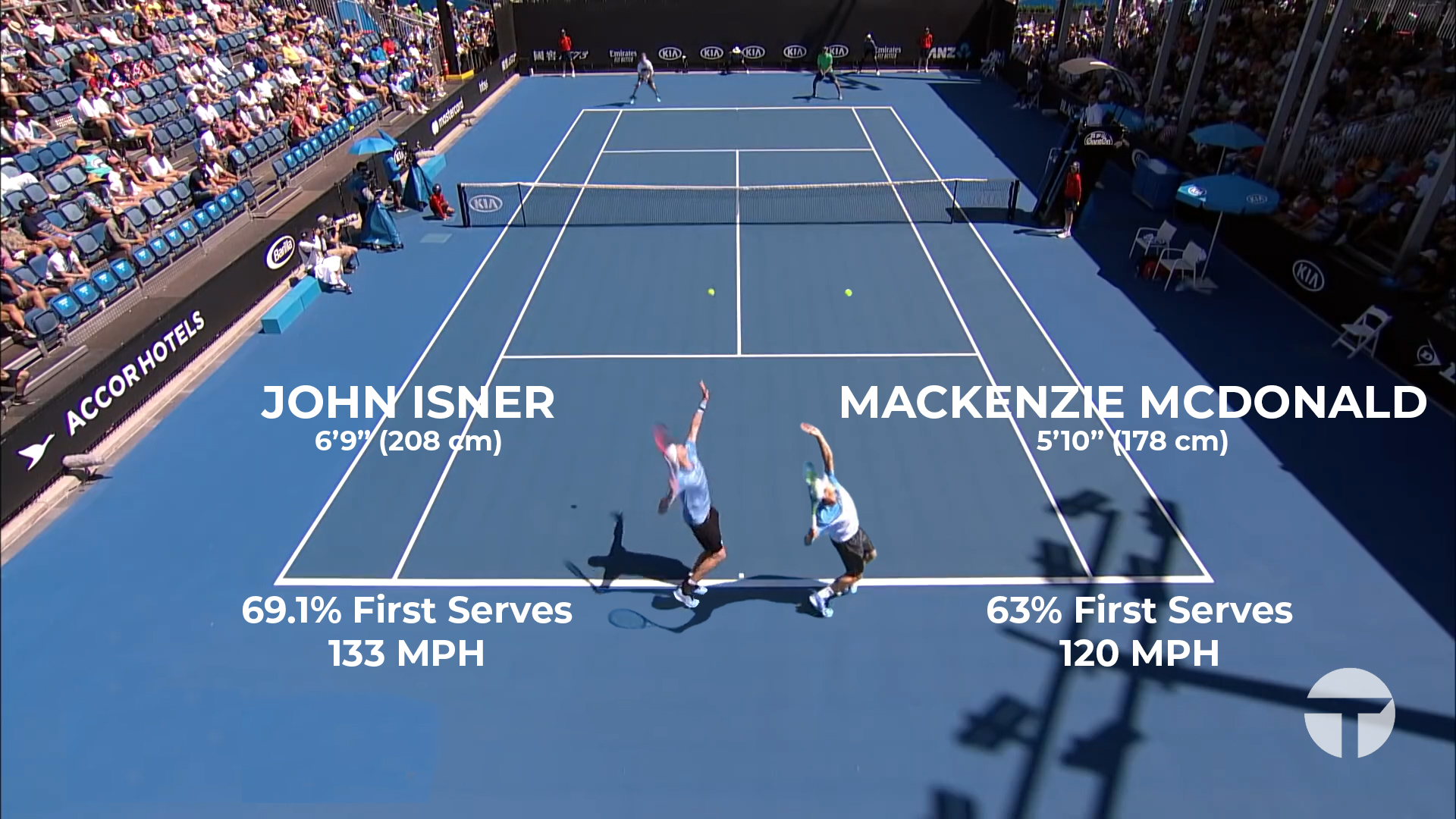

The image above shows John Isner (6’9) serving at the Australian Open in 2019. To his right is Mackenzie McDonald (5’10), serving on the same court at the same tournament. We look at the size difference between the two, and intuitively understand that serving is much easier for Isner than it is for MacDonald. Isner is, to use the phrase, serving out of a tree. Relative to Isner, McDonald is serving from down in the weeds.

The interesting thing is people often don’t move past the intuitive understanding that taller is better. In truth it isn’t that taller is better. It is that making contact with the ball at the highest point possible is optimal. The higher the ball at contact, the better the serve can be.

As the contact point drops, we are forced to sacrifice velocity, consistency, or both.

A ball struck at a higher point can be hit harder, with more angle. It has a steeper trajectory into the box and bounces higher which is more challenging to return. A 5’11 player who can jump 12 inches on their serve is better off than a 6’1 player who only jumps 6 inches (all other things being equal).

Trophy Position

The trophy position is such a telling moment in a service motion. Everything up until this point has been preparation – movement to get us to this position. In its totality the trophy position is our setup for so many things – the jump, hip/shoulder rotation, arm action. Combined, these things impact control, disguise, and power. Since we are focusing on the jump in this article, we will look primarily at the trophy position as it relates to the jump.

Best Jumping Practices

Since we don’t get a running start on the serve, it might be helpful to look at how the best standing jumpers in the world do it. Many people expect professional basketball players to be the best standing jumpers, but it’s actually NFL athletes. Playing in the NFL requires more raw explosiveness. This is part of why they test jumping ability at the NFL combine every year.

So let’s take a look at Byron Jones. Jones is the greatest jumper in NFL history – his standing broad jump was over 8 feet long! But for our purposes, he also put up an astounding 44 inches (112 cm) with a vertical standing jump.

Note the starting position for his jump. Bends at the ankles, knees, and hips. Arms are swept back. Every piece of his body is poised to generate upwards momentum with maximum explosiveness. Such a starting position would be absurd for a serve. The idea is not to copy Byron Jones’ jumping position exactly, but rather to ask ourselves a question.

What elements of these jumping mechanics can we incorporate into our own trophy position without negatively impacting other elements of the service motion?

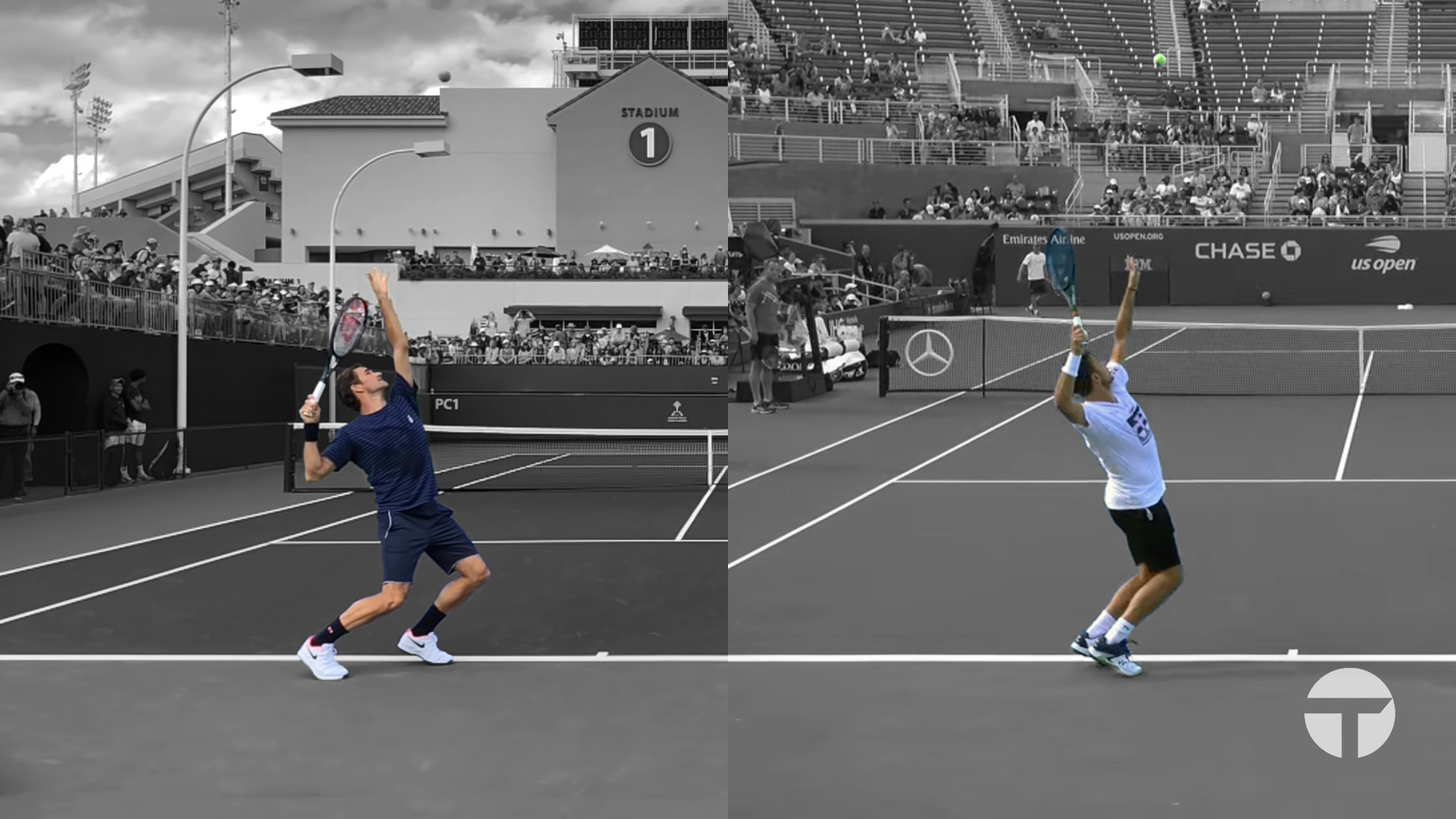

Wawrinka and Federer’s Trophy Positions

The differences between the two are fairly quickly apparent. Federer has a greater degree of flexion in his knees. His stance is a little wider, his hips and shoulders significantly more closed off to the court. For the purposes of examining the jump, the rotation matters less to us right now (although it does impact other elements of the serve).

Federer doesn’t just have a greater knee bend, though. The other important facet is flexion at the hips. We gain power from our posterior chain as it straightens – hip extension is a critical part of that process. In his trophy position, Stanislas Wawrinka has little to no flexion of the hip, which means he can get little extension (essentially only what extension he can manage past a neutral hip position).

The Difference At Contact

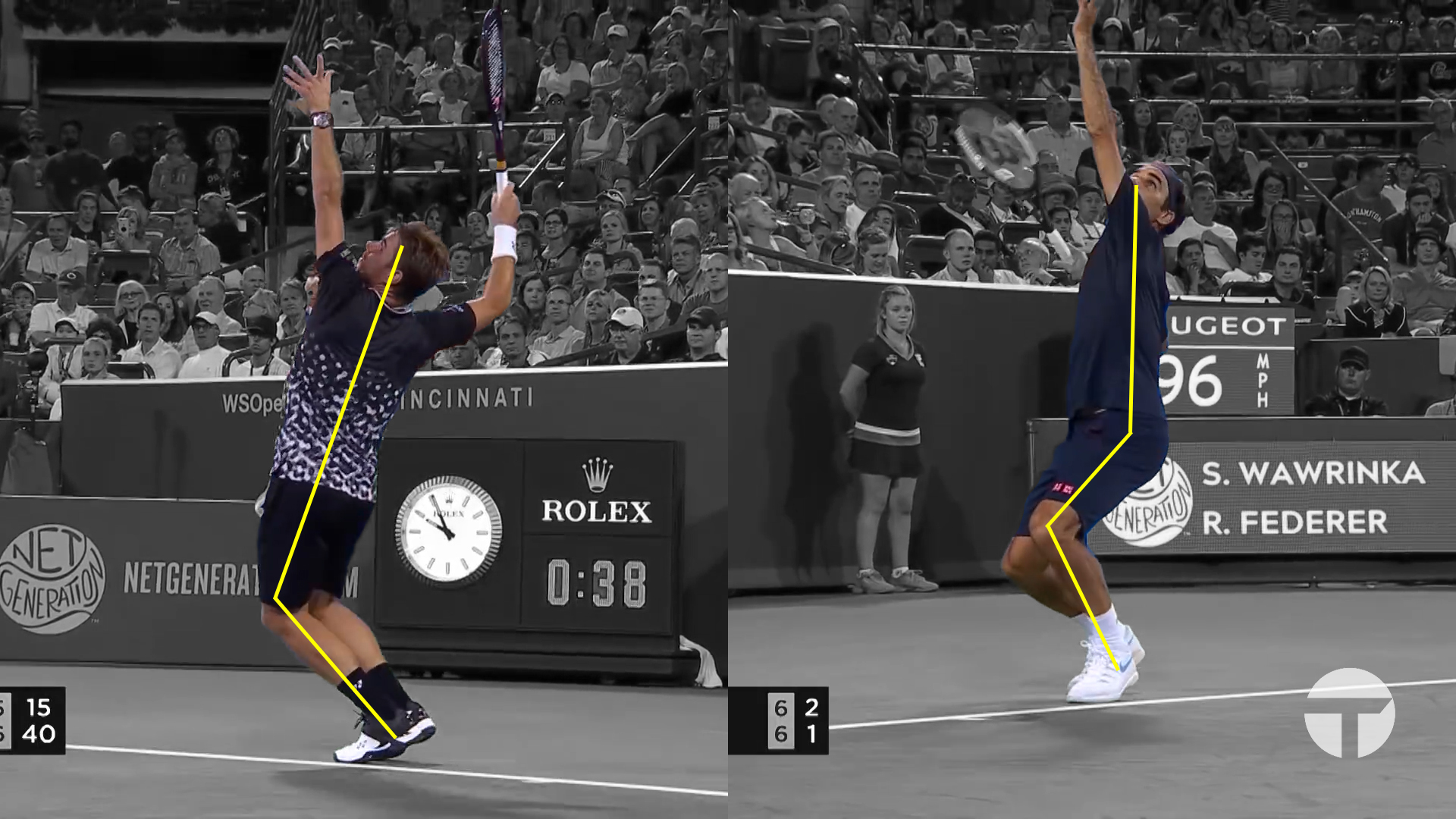

All of this brings us to the height at contact. Nobody watching Wawrinka and Federer serve would claim that Wawrinka is putting less effort into the motion. If anything, the opposite would appear true. And yet, here is the difference between them at the point of contact.

This image is to scale. The difference in the height of their jumps for the serve is actually this large. Which brings us back to 4%. There are some other factors that impact first serve percentage. Technique, spin, neurological performance (targeting) are just a few of them.

Other aspects of Federer’s serve are undoubtedly superior to Wawrinka’s. However the single biggest impact on the difference in their first serve consistency is likely to be the difference in their jump. We are dealing with two elite tennis players – one arguably the greatest ever, and the other who has built a hall of fame resume in the toughest era in men’s tennis history. Both have amazing neurological performance, and both hit a heavy first serve. But Roger jumps significantly higher than Stan. This increased elevation at contact grants Federer better access to the box, which has a direct impact on first serve percentage.

Conclusion

It is clear that gaining more height at contact is beneficial to the serve. Increasing our leg strength and explosivity is one way we can increase that height. Improving our service technique is another. By adopting better elements of vertical jumping technique (such as greater knee bend, or more hip flexion) into our trophy position, we can bring our first serve percentage up considerably.

The challenge is doing so without compromising other elements of the serve. After all we still need to have the arms in positions that allow for good attack angles to the ball. There are significant benefits to having rotation of the trunk towards the back of the court. These are just some of the other things we need to incorporate. Finding the balance is part of the journey in progressing from mediocre to good, or good to great.

-

Man In The Shadows – Stan Wawrinka

The image of Stan Wawrinka weeping as he left court after the epic five-set match with Novak Djokovic are seared into the brains of many viewers as much as the scintillating tennis both men played. In an age when most players roll over and play dead for the ‘big four’ (and truth be told for the top 5 given Ferrer’s record against players not named Nadal, Djokovic, Federer or Murray in the last two years), Wawrinka clearly came to play. Stan wasn’t just playing to avoid embarrassment as has become common against Djokovic – Wawrinka wanted to win. But Stan is hardly a household name outside of true tennis fans despite cracking the top 10 back in 2008 and winning an Olympic gold medal in doubles with Federer. Who is the man with the backhand? What makes his game tick and given the level of tennis he was able to bring against Djokovic on Rod Laver Arena, why haven’t we seen more of him on the big stage in recent years?

(more…)